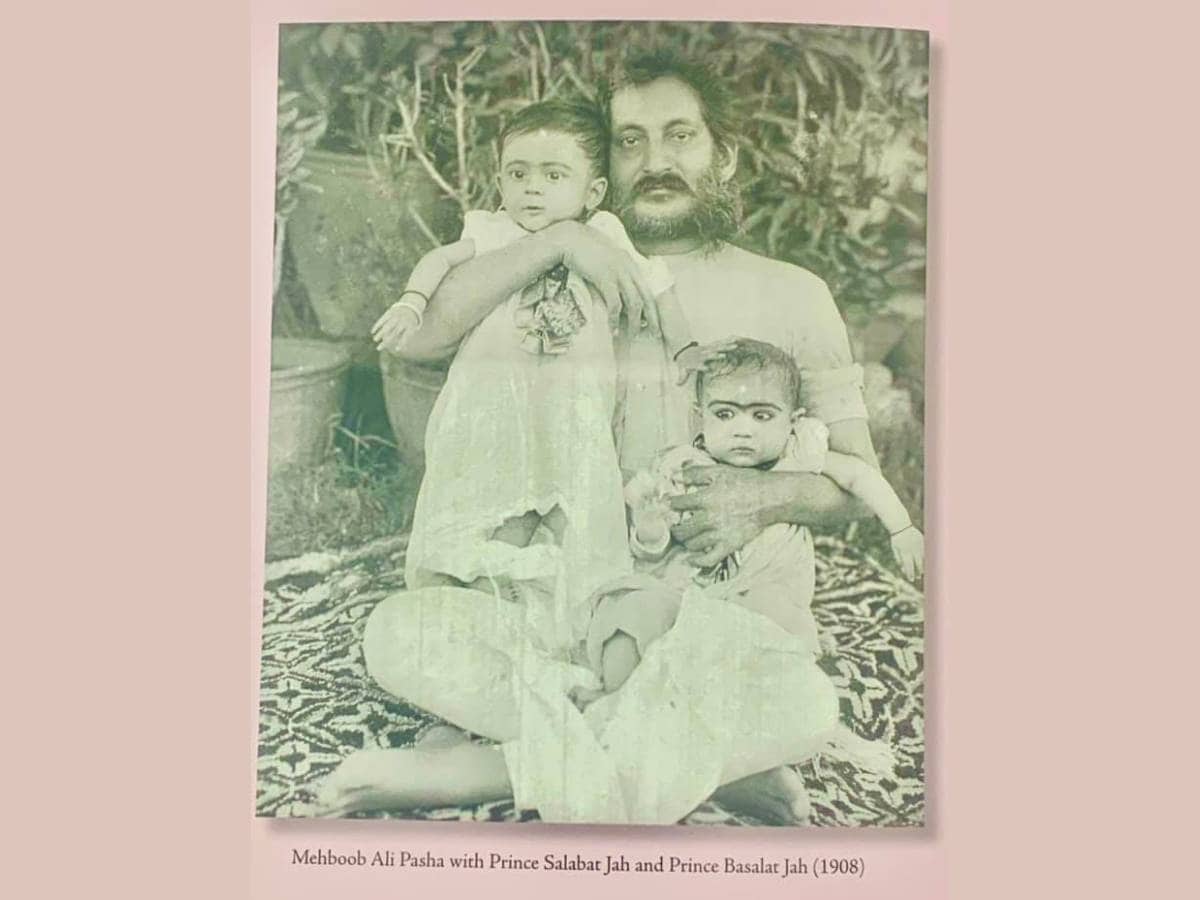

In the opulent Purani Haveli, Sahebzada Mir Ahmad Muhi ud-din Khan Bahadur Salabat Jang Salabat Jah, was born to Ujjala Begum in 1907.

He was popularly known as Salabat Jah.

Privately educated and destined for a life of royal privileges, he remained unmarried and died under a cloud of suspicion, believed to be accidental poisoning, in a mansion at Begumpet on March 2, 1934.

Salabat Jah was rumored to be the favorite son of Mir Mahboob Ali Khan, Asaf Jah the Seventh. Among Asaf Jah VI’s three surviving sons, the line of succession appeared clear: Shahzada Mir Osman Ali Khan (later Asaf Jah VII), followed by Sahebzada Nawab Salabat Jah, and Sahebzada Nawab Basalat Jah.

Yet, a shadow of “what if” lingered. During his lifetime, Asaf Jah VI established a lavish trust solely for Salabat Jah. This trust, a testament to his affection, encompassed a sprawling 81,601.86 square yard estate in Mumbai’s prestigious Malabar Hills, acquired in three parts in 1909 and 1910 for Rs. 12,06,642. This estate was to be managed by a council including Nawab Mutahavvur ul Mulk, Nawab Dawar ul Mulk, Sir Afsar ul Mulk, Nawab Ghias Uddin (later Nawab Azhar Jung), Rai Murlidhar Raja (later Raja Fateh Nawaz Want), and Mirza Abdur Rahim Beg until Salabat Jah became a major. Ujjala Begum was also to receive a monthly allowance of Rs. 2,000.

The sudden demise of Asaf Jah VI in 1911 irrevocably altered the course of events. Mir Osman Ali Khan, then 25 and deemed capable, ascended the throne. Salabat Jah and Basalat Jah, mere four-year-olds, were relegated to the sidelines. Whispers persisted that Salabat Jah was the rightful heir, his claim usurped by circumstance.

Following Osman Ali Khan’s succession, the Viceroy was influenced by accounts of injustice. The half-brothers, it was said, were virtual prisoners, their incomes slashed, and properties confiscated. The original trust was allegedly dissolved or replaced with trustees Akbar Hydari, Richard Trench, and Mehdi Yar Jung, who were accused of neglecting the princes’ welfare.

A confidential letter, penned in 1927 by the British Resident at Hyderabad to the Viceroy, mentioned, “Salabat Jah was a favourite with his father. His father, the Late Nizam Asaf Jah VI, tried to induce the Government of India to recognise him as his heir.”

In the 22nd year of Nizam Osman Ali Khan’s reign, a storm of controversy erupted. Salabat Jah was said to possess a letter, given to him by his mother, purportedly written by Asaf Jah VI, naming him as the successor. This letter, sent to a Calcutta lawyer for validation, ignited the Nizam’s fury. He perceived it as a direct assault on his throne and the position of his heir apparent, Azam Jah.

Suspicion fell upon Salabat Jah’s alleged supporters: Sir Amin Jung, Kazim Yar Jung, and Raja Venkat Ram Reddy. Mr. Armstrong, the DGP, was tasked to investigate, delving into the private lives of these men. However, later in a private interview, the Resident at Hyderabad presented a counter-narrative, assuring the Nizam of Salabat Jah’s loyalty and dismissing the DGP’s report as flawed.

Salabat Jah, tutored by Major Gough, was slated to be placed under the tutelage of the renowned Marmaduke Pickthall. However, Salabat Jah, yearning for a deeper connection, repeatedly requested the appointment of Professor Aga Hyder Hasan Mirza, with whom he shared an intimate bond. He even expressed his inner turmoil through his writings, using the pen name “Nashad Asifi,” meaning “cheerless Asif.”

This article will also demonstrate the exaggeration of British correspondences that contradict their English subjects’ accounts of the liberties and protocol accorded by H.E.H. to his half-brothers, who were consistently included alongside the heir apparent and sons in state events and private gatherings. (Ref: “Loyal Enemy” by Anne Fremantle (1938), published by Hutchinson & Company Limited.)

The author of the same work notes, “Saturday evening, I attended a boy and girl dance at ‘wood side’ with Salar Jung’s party, including Salabat Jah and Gough.”

The same book details how, during the Viceroy Willingdon’s Hyderabad visit, Salabat Jah was presented alongside the heir apparent Azam Jah and his brother Moazzam Jah. Later, Salabat Jah was also present at the Viceroy’s dinner hosted at Chowmahalla Palace, all clearly contradicting claims that these half-brothers were confined as virtual prisoners. The 1933 Nizam’s archaeology report details a 15-day tour of Raichur, Gulbarga, and Warangal Districts, where the Deputy Director was tasked with showcasing monuments to Sahebzada Salabat Jah and Sahebzada Basalat Jah.

Examining political events during his reign, including the circumstances surrounding his half-brothers and the “Khaleej-e-Taj conspiracy,” is conducted objectively. The assertion that Osman Ali Khan was insecure in his position is merely quoted in the context of the available historical record.

S M Aun Mehdi is a scholar of history and heritage of Hyderabad State.