London: UK scientists have found new types of plastic-loving bacteria that stick to plastic in the deep sea that may enable them to “hitchhike” across the ocean.

The team from Newcastle University in the UK showed for the first time that these deep-sea, plastic-loving bacteria make up only 1 per cent of the total bacterial community.

Reporting their findings in the journal Environmental Pollution, the team found that these bacteria only stick to plastic and not the non-plastic control of stone. It may be able to ‘hitchhike’ across the deep sea by attaching to plastic, enhancing microbial connectivity across seemingly isolated environments.

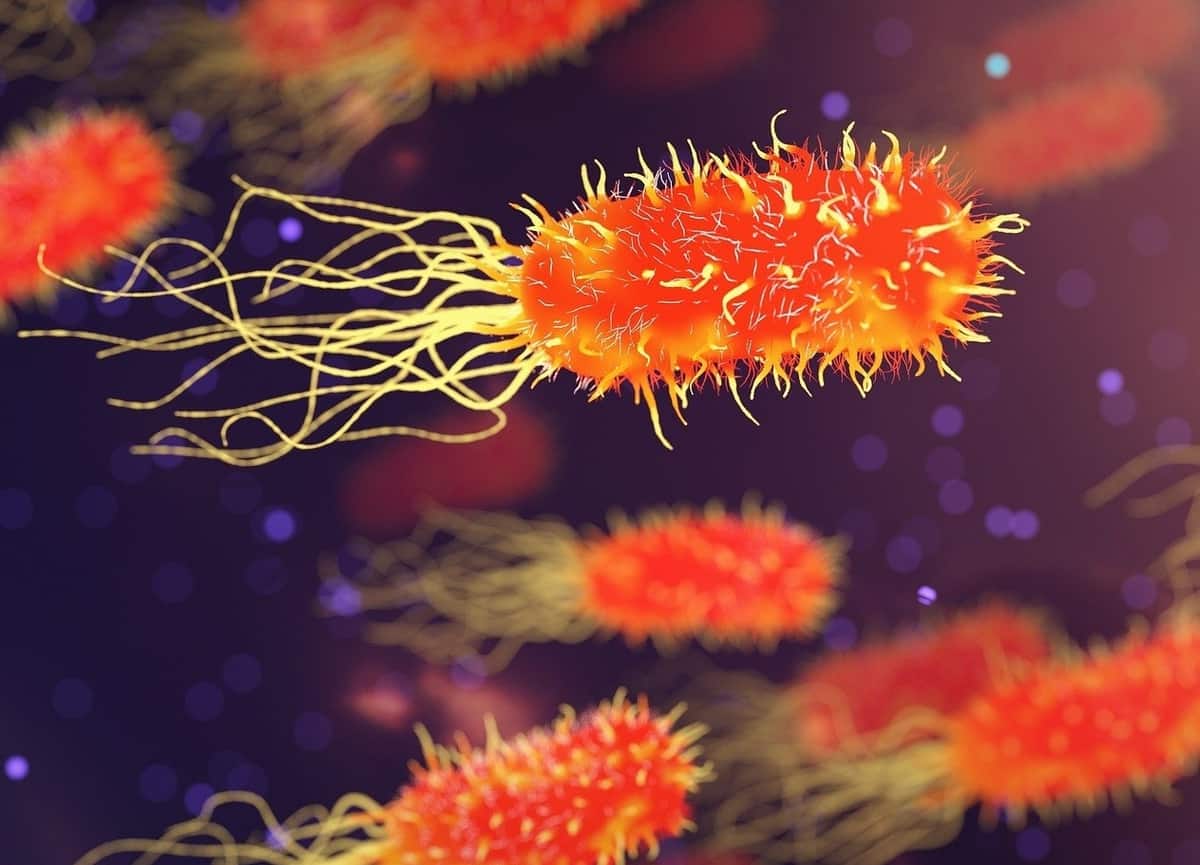

The scientists observed a mix of diverse and extreme living bacteria, including Calorithrix, which is also found in deep-sea hydrothermal vent systems and Spirosoma, which has been isolated from the Arctic permafrost.

Other bacteria included the Marine Methylotrophic Group 3 — a group of bacteria isolated from deep-sea methane seeps, and Aliivibrio, a pathogen that has negatively affected the fish farming industry, highlighting a growing concern for the presence of plastic in the ocean.

They also found a strain of rust-eating microbe named Halomonas titanicae that loves to stick to plastic and is capable of low crystallinity plastic degradation.

To uncover these mysteries of the deep-sea plastisphere, the team used a deep-sea ‘lander’ in the North-East Atlantic to deliberately sink two types of plastic, polyurethane and polystyrene, in the deep (1,800 metre) and then recover the material to reveal a group of plastic-loving bacteria.

This method helps tackle the issue of how plastics and subsequently, our understanding of the plastisphere – microbial community attached to plastic – are sampled in the environment to provide consistent results.

“The deep sea is the largest ecosystem on earth and likely a final sink for the vast majority of plastic that enters the marine environment, but it is a challenging place to study,” said Max Kelly, a student at University’s School of Natural and Environmental Sciences.

Combining deep-sea experts, engineers, and marine microbiologists, our team is helping to elucidate the bacterial community that can stick to plastic to reveal the final fate of deep-sea plastic,” Kelly added.

Microplastics (fragments with a diameter smaller than 5mm) make up 90 per cent of the plastic debris found at the ocean surface and the amount of plastic entering our ocean is significantly larger than the estimates of floating plastic on the surface of the ocean.

Although the plastic-loving bacteria found in the study here represent a small fraction of the community colonising plastic, they highlight the emerging ecological impacts of plastic pollution in the environment, the researchers said.