I wrote the following passages in 2015. This was discovered by a friend in her files. She sent it to me on the condition that I will not be naming her if I ever use it. I found the write up, barring a few paras that have become dated, relevant to present circumstances. It also coincides with the birth anniversary of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, a pioneer of modern education among the Muslims of the Indian sub-continent. Hence the detour.

The phenomenal rise of the Islamic State and its promise to take Muslims back to the era of caliphates has become a global problem. The reach and influence of IS, an entity that is not recognised by any country, is on such rapid ascendance that its reverberations are being felt in India too. A large number of Muslim youth across the globe appears to be falling prey to the incessant propaganda of the IS through social and other media.

Muslim intelligentsia including noted scholars of Islam have been condemning the IS, its use of cold-blooded violence and its objectives…

The idea of caliphate started losing its appeal as many as 150 years ago. Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, the pioneer of modern education among the Muslims of the Indian sub-continent, said, “A present day analysis clearly shows that no one is worth the title of Imam and also no one, not even a head of state, is worth being entitled to be called a khalifa (caliph) of the prophet.” In an article titled Imam aur Imamat (in Urdu) he pointed out, “Although Muslims governing an area can aptly call their monarch as sultan (king) of that country, and in fact they are actually sultans, whatsoever they may call themselves.”

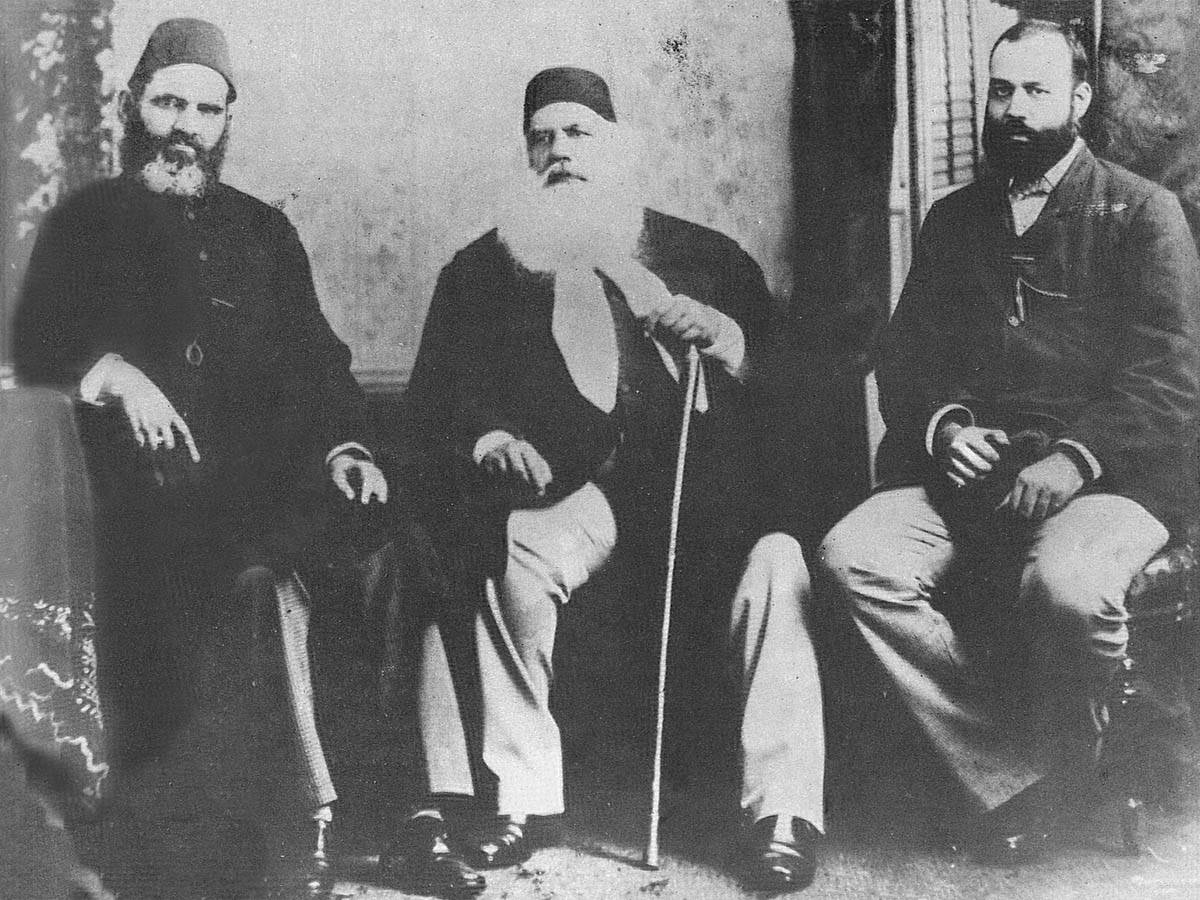

Sir Syed Ahmed Khan known for establishing the Aligarh Muslim University was born in Delhi (October 17, 1817) only two years less than two centuries ago. He died in Aligarh (March 27, 1898) only two years before the close of the nineteenth century.

Though it is clichéd but could be said that he was born ahead of his time. He was a radical in more than one way who had witnessed the trauma of the revolt of 1857 — also called the First War of Independence.

The tyranny unleashed by the Brits in the aftermath of the uprising was too harsh for any Indian.

Bahadur Shah Zafar, the powerless last Mughal Emperor, was forced to accept the leadership of the uprising by the mutineers. After crushing the ‘mutiny’ the British colonialists slaughtered his two sons Mirza Mughal and Mirza Khizr Sultan and grandson Mirza Abu Bakr and sent their heads to the prisoner-emperor. Finally, he, his wife, and a few other family members were sent in exile to Rangoon, the then capital of Myanmar.

In India, the colonialists launched a witch hunt against the Hindus and Muslims who they suspected were behind the uprising. Their main target was the Muslims. Men were killed, women dishonoured and property confiscated. This was the time when Syed Ahmed Khan was associated with the East India Company as a jurist. The pains of the uprising worked differently on him. He decided to build bridges between the Muslim subjects and the Brits and worked tirelessly to achieve that goal.

He felt that illiteracy and orthodoxy were the main causes of the steep downfall of Muslims. He tried to instill rational and scientific thinking among them through his writings. Since the British had replaced Persian with English as the official language he thought it prudent to attract Muslims to the language of the ruling elite. He established Mohammadan Anglo-Oriental College to promote modern education. The college grew to become Aligarh Muslim University in 1920.

While his writings were largely appreciated, what became hugely controversial was his exegesis of the Holy Quran where he departed from the traditional interpretation and presented his own understanding. For this, he was called a deviant and his commentary of the Quran never became a popular point of reference.

Time has its own quirky ways of resurrecting ideas that might have been long buried. When it became known that the Aligarh Muslim University had decided to celebrate the bi-centenary of Sir Syed in two years, there appeared a proposal among groups of Aligarians on the Internet. It said that the university, among other works of the founder of AMU, should also reprint the exegesis written by him.

The proposal triggered a storm. Some called it divisive and others said not publishing the commentary would be tantamount to censoring Sir Syed. Some of the “more intelligent” among the Aligarians believed that such discussion should have been confined to Aligarian groups indicating that they alone should have a monopoly over discussion on the ideas of the thinker and activist who was born and died in British India.

What is drowned in the din is the focus on the main contribution of Sir Syed – which is the need to spread modern education. In spite of the Education Movement launched by Sir Syed about 150 years ago, it has been said again and again that Muslims have not risen to the desired level of literacy. Recent independent and government-sponsored studies have revealed the shocking fact that Muslims are as backward in education and economics as Dalits—a group of people who have been oppressed for thousands of years.

The bi-centenary celebrations of Sir Syed should serve as a wake-up call for Muslims in India to sift through his ideas, pick up what is relevant today, and carry them forward.