By Viplav Bhoomi

Hyderabad: Children who grew up in rural Telangana in the 90s would remember their grandfathers taking them on a mini-expedition to sight the beautiful Paalapitta, also known as Indian roller or Blue Jay, on Dasara.

Now, three decades later, it is hard to find the ‘farmers’ lucky bird’ as their population has declined by over 30 per cent in the last 12 years, according to ‘State of India’s Birds 2020’ report.

If you are lucky, you may still spot the bird in urban green hotspots like the Public Gardens, OU and HCU campuses, and in the rural areas.

According to the report, 14 species of birds across the country, including the Indian roller, have been recommended for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List reassessment.

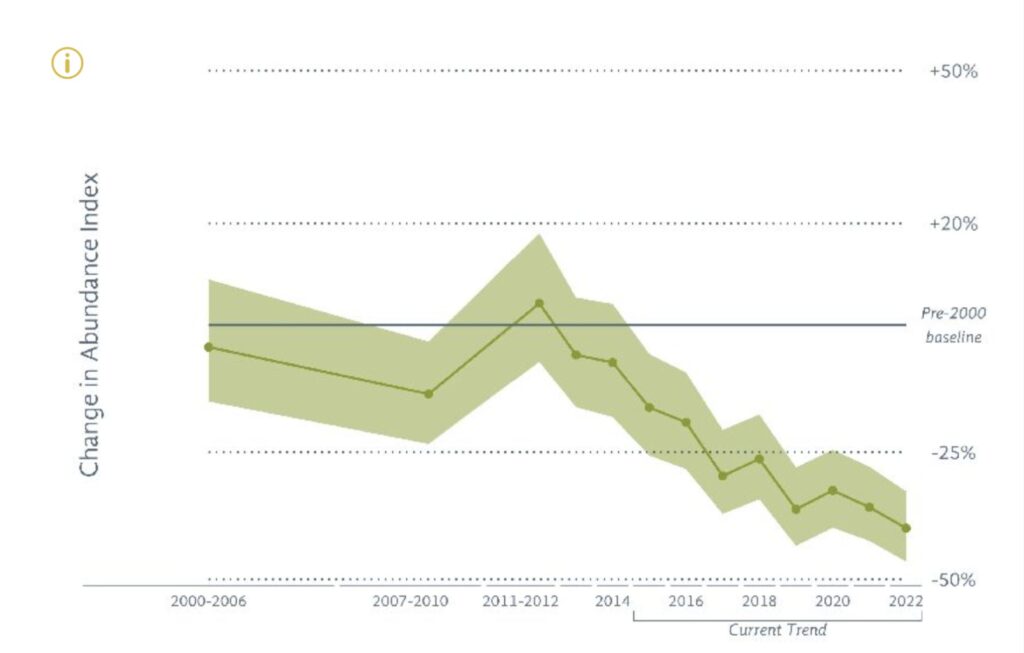

The ‘change in abundance index’ of the Indian roller shows a steep decline in its population since 2011-12. Though it has been placed among the ‘high priority’ species, out of the total 178 species in that category, 51 per cent (90 species) have been marked as being of ‘least concern’ as per its global status. However, as per the inputs received from India, Paalapitta is considered ‘near threatened’ species.

Farmer’s friend

Paalapitta’s importance in Telangana is due to the role it plays in agriculture. It is an omnivore which feeds on the pests affecting the crops. It is for that reason farmers believe that sighting the bird in the area around the farm means prosperity.

It is probably the reason why it is the state bird of Telangana, Karnataka and Odisha. There is also a local superstition that the ancestors take the form of Paalapitta and come to see those alive, and sighting them is like receiving their blessings.

Though the reasons for the decline in the population of Indian roller are many, some of them are preventable.

Existence under threat

For instance, the habitat of the Indian roller is the open habitat where these birds live in the hollows of old, tall, and dead trees. Such trees can hardly be seen anywhere now as they are axed for various purposes.

The belief that sighting Paalapitta on Dasara is a good luck sign has also threatened its existence. Poachers, who capture and cage these birds to show them to the people on the festival for a price, continue to impact them.

Moreover, indiscriminate use of pesticides has diminished their primary food source — the crop-damaging insects.

Policy intervention needed

Sriram Reddy, consultant for National Biodiversity Authority, who is also a passionate bird-watcher, writer, blogger and a trainer, told Siasat.com that grasslands which used to be considered as wastelands decades ago, have been on the decline, and governments have now started recognising the importance of those lands as various bird and animal species depend on them. Reddy suggested having a policy-level intervention to protect those species like the Indian roller in the grasslands, just like we have protection for forest areas.

Another observation of his is that most of these birds depend mostly on shallow water bodies, mostly in the catchment areas of tanks and reservoirs, where their habitat is best for feeding and living.

“This is the reason why we don’t find that many birds like ducks in the catchment areas of Ameenpur lake, where that area has been encroached. Still water will be there in the lake, but when the lake dries-up, it will become prone to encroachment,” he said.

“The solution lies in the problem itself.”

State of India’s birds

As per the ‘State of India’s Birds’ report, out of the total 942 species which were estimated and classified into categories of conservation priority in India, 178 were considered as high priority, 323 as moderate priority and 441 as low priority.

Of the total 942 species, there was insufficient data for estimating the long-term trends of 419 species and insufficient data for estimating current annual trends of 299 species.

The assessments in the report were built on 50 million records obtained from 30,000 bird-watchers from across the country. After the initial report which was released in 2020, more data uploads were made, accompanied by several refinements in analytical methodology, which is a continuous process.

The report was a collaborative effort of the Centre for Ecological Sciences, IISC, Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Wildlife Trust of India (WTI), National Biodiversity Authority (NBA), National Centre for Biological Sciences- Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, World Wildlife Fund (WWF), South India Centre of WII (SACON), Zoological Survey of India, Nature Conservation Foundation, Wetlands International, aTree and BNHS India.