Alexander the Great was fortunate: he spliced the Gordian knot only once. Dr. Ishrat Husain, swordless, has had to unravel knots every day.

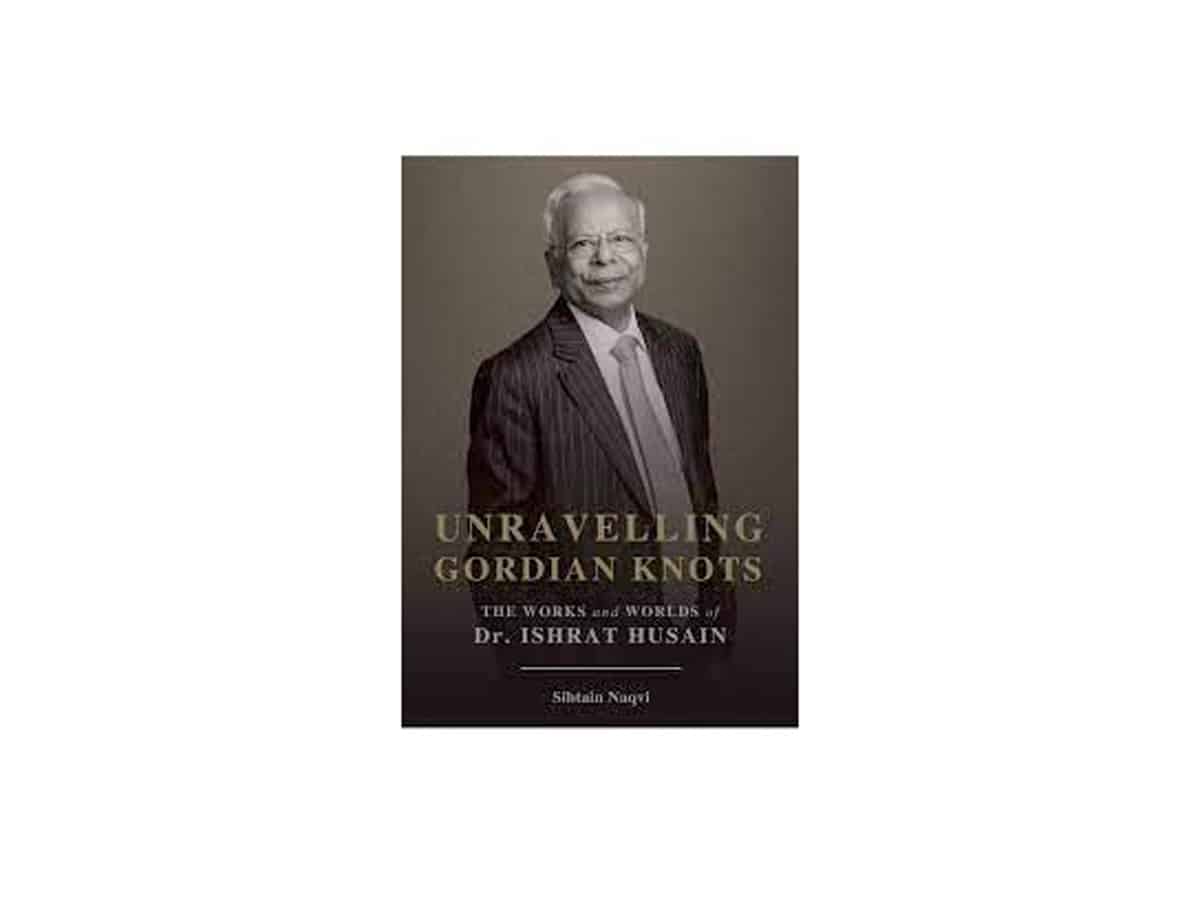

Dr. Ishrat Husain’s career is described in Sibtain Naqvi’s meticulously researched, well-structured biography titled Unravelling Gordian Knots: The works and worlds of Dr Ishrat Husain (2021). Dr Ishrat was perhaps too modest to write it himself. Naqvi is its surrogate parent.

Ishrat’s family migrated from Agra in December 1947. His father established a legal practice in Hyderabad (Sindh), where Ishrat showed precocious promise by clearing his Matric exam at the age of 12. He graduated from Sindh University, then the University of British Columbia (Canada), after which he joined Pakistan’s Civil Service in 1964. That batch achieved a legendary reputation as an elite above an elite, occupying posts from the presidency of Pakistan downwards.

In 1976, Ishrat obtained a U.S. doctorate in Economics and was recruited by the World Bank. It recognised his worth even when his government didn’t. He restructured chronic cases of national insolvency– Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana and finally Nigeria – and returned to the WB headquarters, a proven ‘wunderkind’. His talents were applied to other African countries and the emergent Central Asian Republics.

He had been at the World Bank for 20 years when, in 1999, he was approached by the fourth Cromwell in Pakistan’s history– General Pervez Musharraf. He offered Dr. Ishrat the State Bank governorship, without informing his finance minister Shaukat Aziz.

If The Bank of England’s sobriquet was The Old Lady of Threadneedle Street, the State Bank of Pakistan became the Aged Crone of Chundrigar Road. That creaking institution responded haltingly to the onslaught of Dr Ishrat’s reformist zeal. He pulled its atrophied staff out of their institutional stupor. He separated the bank’s role as the Government’s banker from its regulatory responsibilities. He refurbished the bank’s reputation until it shone like the newly minted coins it issues. The SBP Museum he established is still a popular draw.

After serving two terms as Governor, Dr. Ishrat expected the traditional laurel of the finance ministership. His turn-around of forlorn African economies was credential enough. But Shaukat Aziz (by now prime minister) refused to relinquish the FM-ship, claiming that it was the ‘only real job’ he had.

Although, Pakistanis complain that the government is bloated, none is prepared to prescribe the right diet. In May 2006, Dr. Ishrat was given that opportunity as Chairman of the National Commission for Government Reforms, reporting directly to the prime minister and the president. He must have recalled the lesson he learned at Sindh University: ‘In order to be heard and obeyed, one must have access to the corridors of power; that one must be a “somebody” to enjoy the privilege of getting things done.’

Ishrat’s Augean labour was ‘to undo decades of malaise [,] to drain the swamp that the civil services had become and waft away the miasma of nepotism, corruption and incompetence that hung around it.’

During the twenty-two months he served as Chairman, Dr. Ishrat held extensive consultations at the federal, provincial and district levels. His report was exhaustive in its scope and exhausting to read. Naqvi quotes Mr. Sartaj Aziz (a former Finance Minister): ‘I advised Ishrat not to write a long report; instead, write short reports on different subjects, and get Musharraf involved [.] By the time the report was finished, Musharraf was on his last legs and the report – one of the best on organisational reforms – was not implemented because it was delayed’.

Later, Dr. Ishrat expanded this diagnostic study into a 568-page book Governing the Ungovernable: Institutional Reforms for Democratic Governance (2018), grouting his reputation as an oracle whose advice is sought but never followed.

From conducting post-mortems on the bureaucracy, Dr. Ishrat turned to educational paediatrics. In 2008, he joined the IBA in Karachi University as its Dean. During his eight years there, he revitalised its stultified organisation and mobilised the business community to support its nursery. He left it in 2016, $50 million richer, with a motivated student body, and a rejuvenated faculty of 56 PhDs. In parallel, he supported cultural causes, amongst them Zia Mohyeddin’s under-appreciated NAPA.

A former student of Dr. Ishrat (now an ambassador) once observed: ‘He always had his eye on the next rung of power.’ In August 2018, Dr. Ishrat returned to Islamabad. Imran Khan enticed him into becoming his Advisor on Institutional Reforms and Austerity – a post he continues to hold, with more gravitas than authority.

Dr. Ishrat came from the World Bank. Unlike similarly imported reformers like Shahid Hosain, Moeen Qureshi, and Shahid Javed Burki, he did not return to the mother house. He chose to stay on, to serve the country he adopted in 1947, to become one of its more imitable sons.

Fakir S Aijazuddin is a noted thinker and columnist of Pakistan

Source: Dawn