The irresistible articulation of the human mind-language – converts the past, present, and future into an eternal presence that creates a sense of cohesion in a chaotic, hostile, and almost monstrous world through its fluidity, ambiguity, and uncanny ability to make meaning unceasingly. Language shapes our identity and provides much-needed emotional sustenance through religion, culture, and ideology, offering overlapping layers of conscience that conjure euphoria and disgust simultaneously. It bestows creative freedom and instils a sense of ipseity in each one. It mirrors not reality but existence and explores the realm of human possibilities. It makes us see what we are and what we are up to. It is what the totalitarian regime fears the most, and it tries to make language bereft of diversity and link it to religious identity.

The despotic loons allow the use of only approved phrases and words, restrict the free usage of language, and destroy spiritual and creative freedom. Language becomes a bizarre tool of oppression, and it is used to put tyranny on the path of triumph in all spheres of life. At a time when the land-based government is being replaced by digital governance and feudal global corporations run the show, a dystopian world characterized by stifling restrictions on the use of language came to light in the form of a dazzling yet grotesque spectacle.

Stifling use of language

The regulated and stifling use of language has been converting contemporary society into a surreal dystopian. Margaret Atwood’s novel The Handmaid’s Tale (1985) is a chilling description of the sweltering situation, and so is AynRand’s novella Anthem (1938), which depicts a society where the first person “I” is proscribed, effacing every trace of individuality. Indian writers seldom try to map the terrain of a society closely resembling dystopia.

The graphic depiction of how power-seeker politicians decisively turn an emotion-uplifting and stimulating activity into a vexatious act in the citadel of intellectual freedom and plurality largely eludes us. It is the turn of the celebrated author Dushyant to fashion an intriguing narrative of how language is used as a means of violence. His spellbinding story Kabootar (pigeon) upends the notion that when language fails, violence takes on, and the language becomes the dominant abettor of oppression and violence. The advocate, appearing for the victim in a bizarre case, argues: “I humbly submit that the new law stipulates that only Hindus, Brahmins, Muslims and Sikhs can speak Hindi, Sanskrit, Urdu and Punjabi, respectively. The man standing in the court, Pankaj Singh, is a Hindu and teaches science. By birth, he was a Hindu and is essentially a writer who always cites Urdu as his language. He speaks and writes Urdu, and he uses Urdu on social media. Language tradition was never divided on religious affiliations. Regions and communities have a specific language. My client has not committed any crime.”

Unfolding the trial details resembling Kafkaesque execution, the story provides a gripping account of testimonies by the witnesses who put their hands on the diary of the grandfather, Ram Charit Manas, and Deewan-e-Ghalib instead of using divine texts or swearing by their conscience. Shiv Pujan Sahay’s story, “Kahani Ka plot”. The upright judge, a literary connoisseur, found the charge frivolous and the newly enacted provision ludicrous. He imposed a rupee fine on the parliament for passing such an absurd law and wasted the court’s time. The blade crushed a pigeon sitting on the ceiling fan during the trial. It artistically foreshadows what is coming our way. The next day, the newspaper read that the judge was terminated for disrespecting the act, and some unidentified people assaulted the accused, Ghyansham Singh, gravely. The story evocatively showcases how language can be used to mess up a nation’s cultural aspiration psychologically. Its English translation was included in the anthology of selected Hindi-Urdu short stories from India and Pakistan.

Short stories of Dushyant

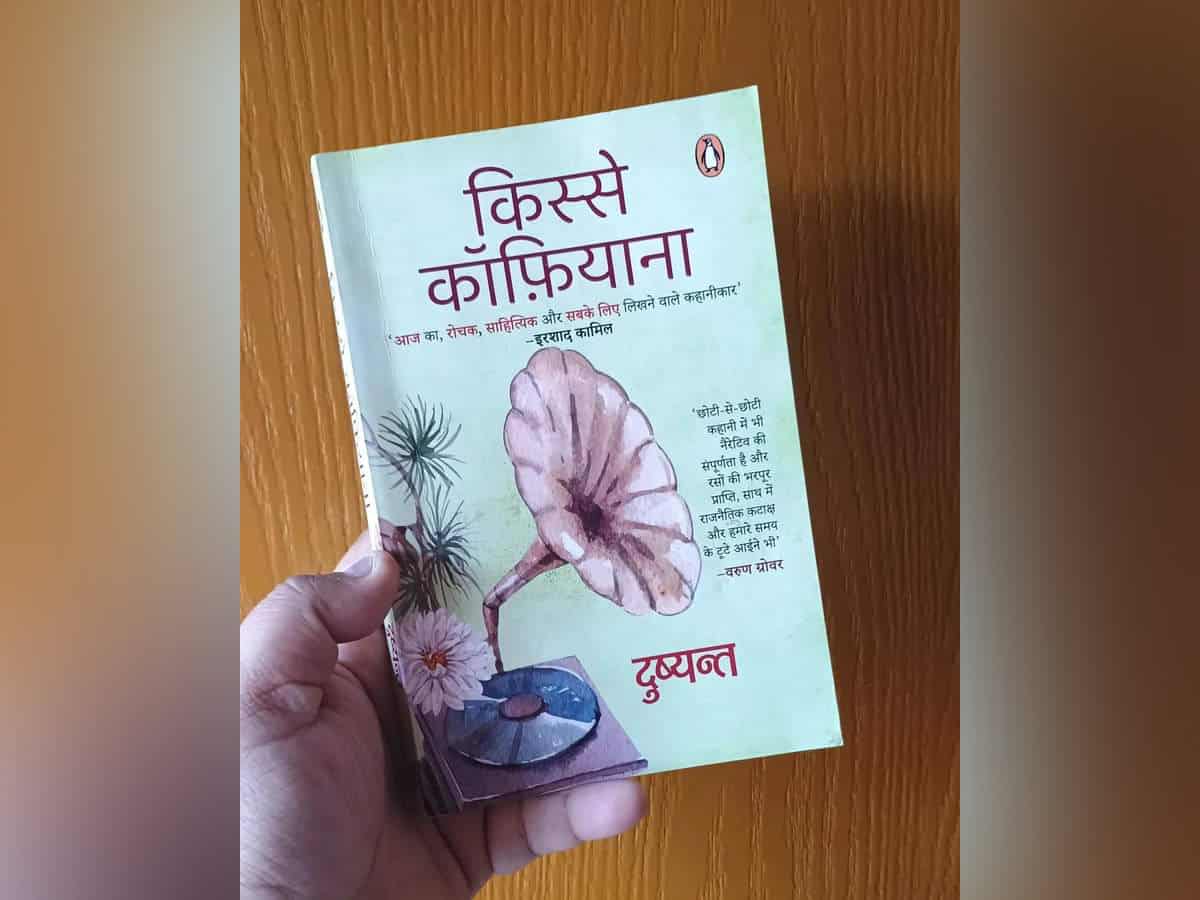

Dushyant, who uses multiple genres with remarkable ease, got widespread acclaim for his laconic and not run-of-the-mill short stories. The collection carries 26 stories that unravel some of the most unusual and complex situations mingled with curiosity, fascination and dread. We are closely connected with the complex web of others that spreads over the past, present, and future. The past, with its tantalizing presence, scares and tempts us. The human relationship makes a go with the ex-partners. Not many see it beyond jealousy and fail to realize that it is more than a source of constant stress. The free-love generation no longer fosters fear and paranoia about former partners.

Dushyant dishes out pulsating tales about a strong resonance of fellow feeling runs for someone who was once one’s thing. The new partners seem empty of malice and envy, and they hardly suffer from guilt that their happiness hinges on someone else’s agony. His astutely rendered story Ekda Ex(Once Ex) evocatively depicts many instances where new partners, Kalyani and Nikhil, seem utterly unperturbed by the fact that their other halves have predecessors whose absence denotes a strong sense of presence. An excerpt bears testimony to it. “Nikhil: will you favour me,’? Yes, sure,” It may sound odd to you !” Nothing is odd, buddy; tell frankly, “Do you find it natural to have the wish to talk to your ex after the breakup? “Yes, it is very much natural; the relationship is not an electric switch that one can turn on and off whenever he wishes. No matter how it took place, the breakup carries much more that remains connected. All is not snapped in a flash. What stays behind, get on with it till death. This persistence betrays essential human nature. By the way, science, too, recognizes the withdrawal system. Let me know the favour: consultancy or counselling?”, said Kalyani, bursting into laughter and winking.

Are exes awful?

Last year, Simon and Schuster published Lucy Vine’s “Seven Exes, which poignantly tells the story of a hero obsessed with awful exes who finds exes not a tragedy but an agonizing and self-inflicted farce. Dushyant’s stories Do Chand aur TeenKahaniy, Sham, Nostalgia, aur Monalisa ki Hansi, Prem ki Upkatha, Life is Grey, Tala Chabi, Beech Sarak par, Prem ka Deh geet, Muskarati hui Ladki, and the like creates an ever-expanding intersection of promiscuity and fidelity with no trace of rhetorical flourish. The narrator seems far from being judgemental, and the intriguing stories revolve around complex and multiple relationships that Vine categorizes as the first love, the work, the mistake, the friend with benefits, the overlap, the missed chances, the bastard, and the serious one. The terse narrative meticulously produced by Dushyant leaves the reader mired in a believable alternate truth that reality obscures. The author seeks to capture the infinity of epiphanic moments in a person’s life. Closely linked to common human feelings, the book Qiasse Qafiyana opens new vistas for the reader’s mind that can change our perception of reality. The stories are a potent metaphor for human frailty and ignorance.

Shafey Kidwai, a well-known bilingual critic and author of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan: Reason, Religion and Nation, teaches at Aligarh Muslim University. Can be reached at shafeykidwai@gmail.com