Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants.” — Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, Gloria Anzaldua.

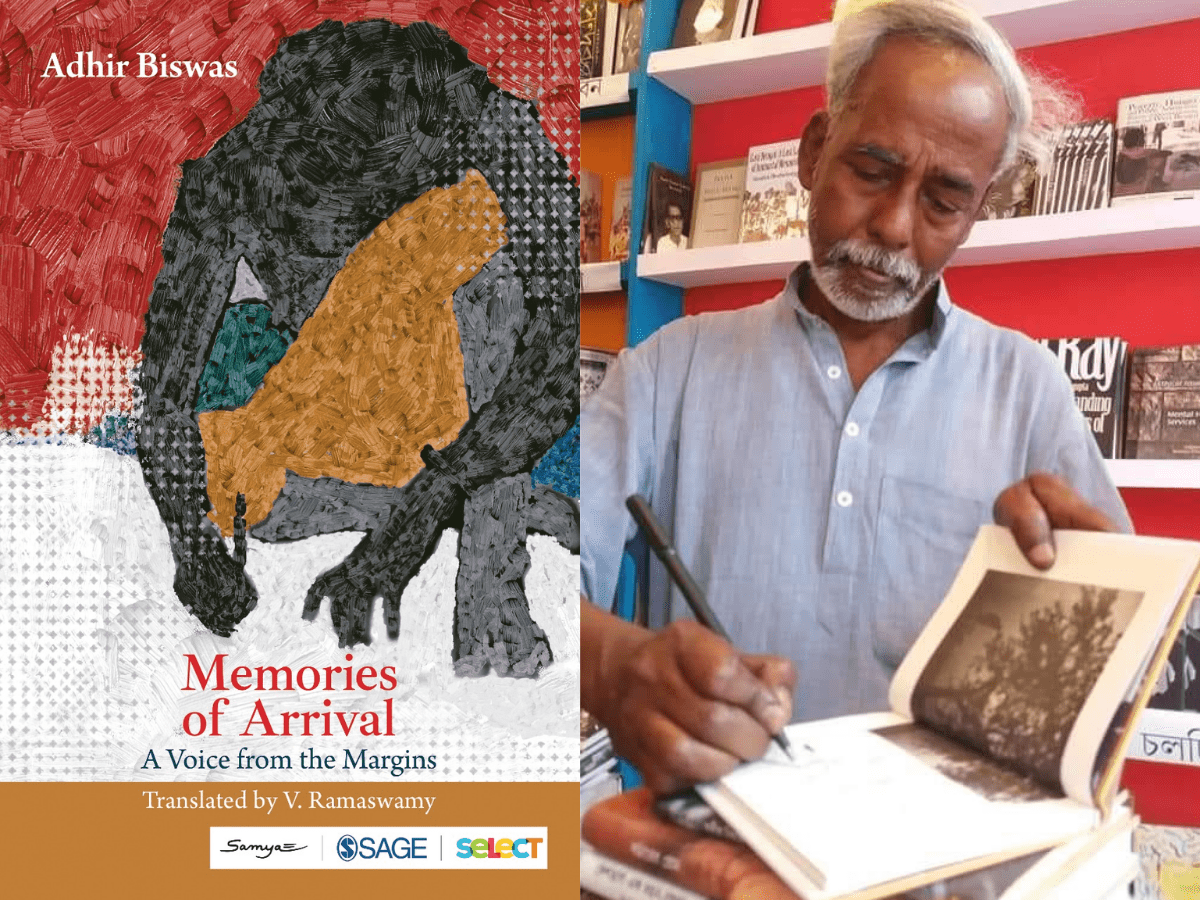

The narrow strip Anzaldua speaks about is more than just a marker stamped on a physical terrain. It digs deep and highlights the distinctions born on either sides. Adhir Biswas’s Memories of Arrival: A Voice from the Margins, translated by V Ramaswamy and published by SAGE Publications India and Samya under the Samya SAGE Select imprint, highlights distinctions: both physical and psychological.

The physical distinction is surely worth talking about. All the partition narratives Indian schools have taught its children, have focused primarily on the Hindu-Muslim, Hindustan- Pakistan binary. These binaries while important, often kill other accounts. Accounts of people unknown, lives unaccounted for.

For instance, Biswas discusses his move from East Pakistan (what we know as Bangladesh) to Calcutta, India. It is a struggle, for sure. One of lands going amiss, money evaporating from hardworking hands and even one of Indian tongues, which wag but refuse to understand the different dialect of Bengali pouring out of a Bangladeshi’s mouth

The memoir, is a proud achievement for Biswas. Even before he starts to tell us his life’s story he tells his reader that he has always dreamt of a translation.

“What if this is available in English? What if this is read in Africa, Uganda, Germany, Japan or America! If on reading, people feel that they too are like me, having left their villages and their countries? Or eve if not exiles, can see a marginal man retelling his life? Can imagine a boy who has lost his homeland?”

There exists in the current political climate a shifting definition of what is public and what constitutes the private. It is a definition we should care about especially at a time when Muslims, Dalits and other minorities find themselves asking, “How long does one have to stay in a place before they call it home?”

Biswas answers it for us via the memoir. Even as he finds charm in Calcutta, its Maidan, Bengali cinema and football, he finds himself time and again thinking of his mother who died in East Pakistan. He tells his reader that his mother would have loved to see the river Ganga. But Adhir’s father, who constitutes an honourable part of his memoir feels differently.

Adhir writes, “Ma did well not to come here. She laid down her body in the country of her father’s home. Every once in a while, Baba said, “How fortunate your Ma was!”

It is perhaps these accounts of displacement which seldom gain popularity. Accounts of escaping from a broken down/conflict ridden place but still missing them as if discomfort and unhappiness is how one defines home.

Even after having resided in India for ages, Biswas still finds himself oddly stranded.

“I don’t have a passport. I didn’t get a passport because I mentioned ‘Magura’ as my place of birth in the application form. I have neither citizenship card nor border slip. I have lived in India for almost fifty years. In my old age, my heart weeps for the village home. Like how before coming to this country, I had gone to the Shatdowar cremation ground to tell Ma—Ma, we are going away!”

Any remnant of Biswas’s nostalgia in his memoir, is tinged with an unexplained grief. At one point in the book he discusses how a Didi (a sister he had never known), died when she was in Class 5. She loved roses, recounts Biswas. When Biswas has a child of his own, the boy walks up to him one day, enthusiastically hoping to plant roses.

Biswas patiently explains to his son the problem with the flower.

“.. She died because she didn’t receive proper treatment. I know, not planting a rose because of that is not correct either. But if you plant it, I’ll be reminded of Didi. I never saw her, but I still feel sad.”

The child, complies and says, “No, Baba, I won’t plant it.”

But that is a striking reminder of how Biswas associates himself with an idea of a home he never really got to know well. It also is striking because this is not Biswas’s account alone. He was not, as he writes, the only East Pakistani who got beaten up when Mohun Bagun lost a football match in Calcutta.

The violence runs deep. It is born out of disdain for Bangladeshis residing in Calcutta and more specifically for Dalits who lived in isolated habitats, slums living off of whatever little kindness the upper castes deigned to offer. To separate Adhir Biswas’s Dalit identity from his account of refugee-ness would be to again kill an important story born out of the post-partition days.

Perhaps, a sensible way to sum up Biswas’s Memories of Arrival is to completely severe oneself from the account and use his own words. A big part of what a reader is likely to feel about the memoir is similar to what Biswas himself feels about noted film-maker Mrinal Sen.

“His film (in Biswas’ case, his writing) made one feel suffocated. No sound. A succession of scenes…. Lives speeding by.”