“Who is he? We don’t know about him.” That is what the unnamed officials of the Central Board of Film Certification reportedly said when denying clearance to a crowd-funded Marathi movie, “Chal. Hallabol”, which loosely translates to let’s go and attack. The movie-makers have been asked to delete the poem titled Raktaat petlela aganit suryano written by the celebrated Dhasal.

The Marathi poem’s title, when loosely translated, means the innumerable suns that are inflamed in the blood. That poem is reputedly why he got his Padma Shree in 1999. It would appear the language used by Dhasal is rich in violent imagery where he preaches – not literally but metaphorically – setting fire to an unequal world.

Sahir Ludhyanvi’s lyrics in the movie Pyasa, of 1957, which had the lines ‘Jala do issay phoonk dalo ye duniya’ had passed muster and had become a popular song. Dhasal’s poem is no different and it has been asked to be cut out. The film makers have appealed against this. They had submitted the film on July 1 last year, hoping to release it on December 6 the same year on the death anniversary of B R Ambedkar.

What is curious is that there is hardly any, even muted, response to this call to delete his poem from a motion picture made by Mahesh Bansod. The world of literature in Maharashtra is silent and so are his cohorts in the Dalit movement. Kumar Ketkar, a former Rajya Sabha member and an editor, does not expect any reaction from the Dalit colleagues of Dhasal because they “are compromised” and are on the side of the Right Wing. Nor is he hopeful of any ‘Brahminical’ literary figure speaking up.

Nor have newspapers given any play save bits of news here and there. An enraged socialist-inclined Sanjeev Sabade, a Marathi editor now a columnist, was enraged enough to write on his Facebook wall that the officials who asked “who is Namdeo Dhasal” should be sent packing out of the Certification Board for their ignorance while their offices are in Mumbai.

In a brief but pungent open letter to Ramdas Athavale, a union minister, on the Facebook page, Sabade asked whether he would fight for retaining the Dhasal poem in the movie or ‘tuck his tail.’ Ramdas is known for his inane versification in his public and even parliamentary speeches and heads one of the factions of the Republican Party of India. He asked Athavale to quit the government, “If the movie was not released uncut.”

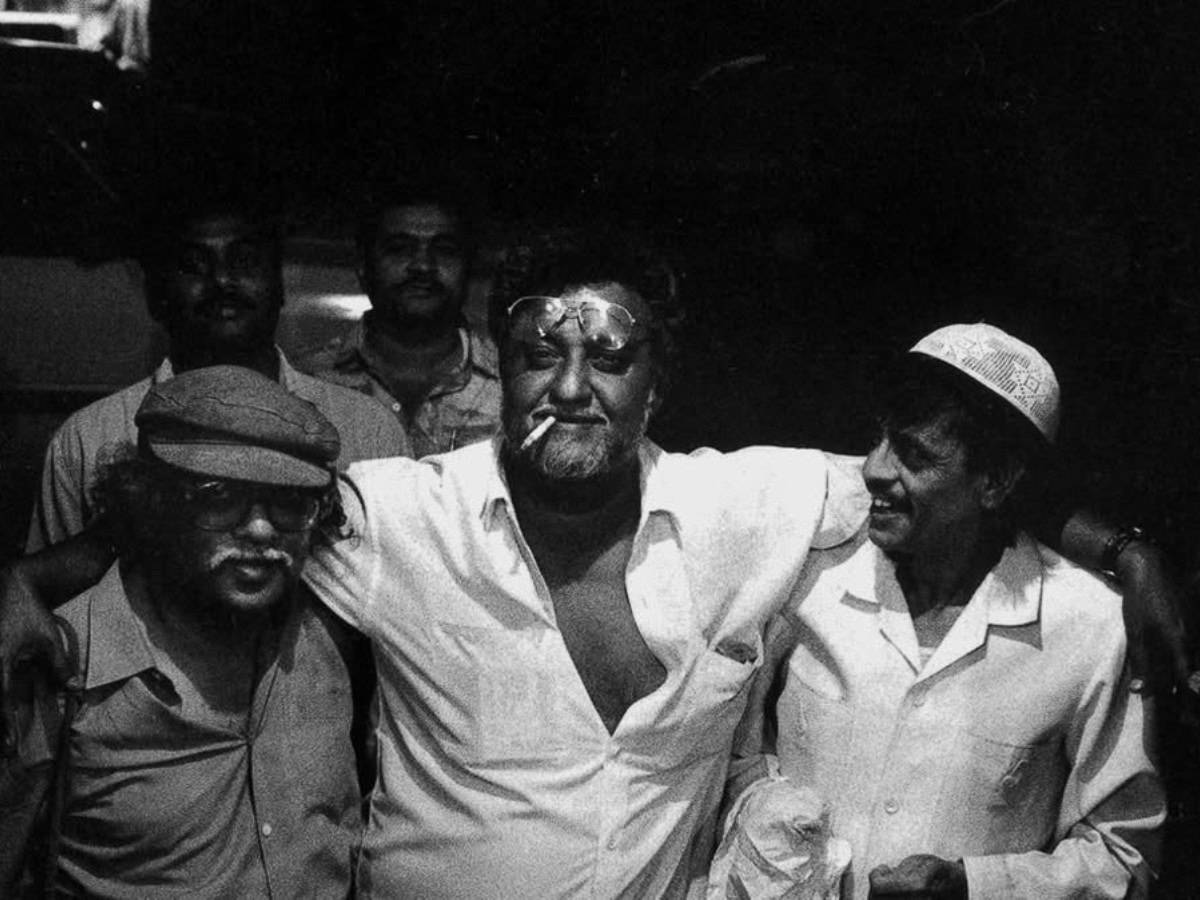

Dhasal is a co-founder of the Dalit Panthers which sought fraternity, bridging the gap between the rich and the poor, the advantaged and the disadvantaged, and in all senses, equality. He was honoured by the Sahitya Akademi’s Lifetime Achievement award in 2004.

He did not hesitate in using strong, colourful language, even profanity, in his writings because his readers were also from that section of this world who speak that language in their everyday life. It was certainly not a part of the traditional, or put in another way, the Brahmanical Marathi literature. He was an instigator seeking a change towards fraternity. The academically venerated Economic and Political Weekly (EPW) had said that Dhasal was challenging the “Brahmanical literature” and his was a ‘new language.’

In essence, this neo-Buddhist, a community of people who were untouchables who converted to Buddhism at the call of Babasaheb Ambedkar, was an Ambedkarite who battled with cancer and alcoholism, and drove a battered Mercedes. But the brand of the car did not match his disheveled persona. He passed away in 2014.

The Time magazine writing about V S Naipaul’s ‘India: Million Mutinies Now’ had this to say – “The lowest of the low, are at least partial winners. As testament to that transformation, Namdeo Dhasal, a militant Dalit (untouchable) leader and poet, tells Naipaul, ‘There was a time when we were treated like animals. Now we live like human beings.” That partial victory was not enough for Dhasal who figures in the book.

So much about Dhasal, a leading figure in Marathi literature centred on social revolt. He had enlarged the meaning of ‘Dalit’ to encompass all oppressed in all categories.

Apart from the cited poem, what kind of poetry did Dhasal write? Here is one translation from Marathi:

A leaking sun

Went burning out

Into the night’s embrace

When I was born

In crumpled rags

And become orphaned.

The one who gave birth to me

Went to our father in heaven.

She was tired of the harassing ghosts in the streets

She wanted to wash off the darkness in her sari

I grew up like a human with his fuse blown up

On the shit in the street.

Like a human with his fuse blown up.

Saying ‘give paisa

Take five curses’

On the way to the dargah. (Translated by Arvind Kumar)