By Khalid Khan

The Sachar Committee Report is one of the first government documents highlighting the marginalisation of Muslim minorities in terms of their socio-economic conditions. The independent studies on the Muslim community reveal that their situation has not improved substantially, even after more than one and a half decades from the Sachar Committee Report. The relative position of Muslims has remained more or less the same at the national level as well as at the state level. This is equally valid for the national capital region of Delhi, despite the fact that it belongs to one of the most developed regions of India. Their condition in the labour market may be used as an indicator to gauge the overall scenario for Muslims in the state.

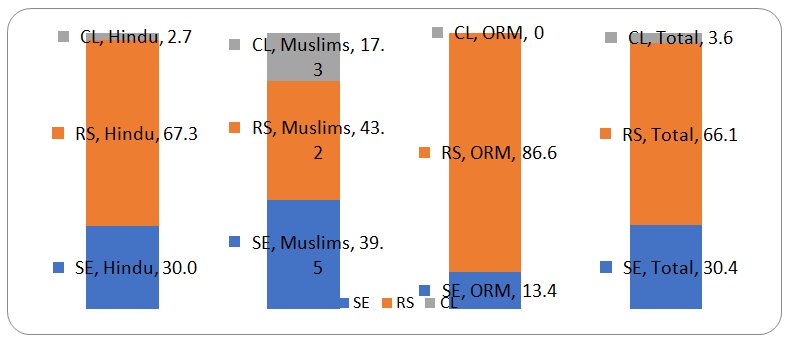

The analysis based on the data from periodic labour force survey for 2019–20 reveals that the employment rate as measured by the work participation rates is 43.3 percent in Delhi, which means that 43 percent of the population in the age group of 15 years and above is working. This figure is close among Muslims, whose 43.8 percent population is working. It is closer to Hindus but higher than other religious minorities. Joining employment is a compulsion for the underprivileged group for survival, while it is a choice for the privileged ones. The Muslims are at a vulnerable position in the labour market despite their employment rate being similar to the Hindus. The disaggregation of jobs by characteristics reveals a high concentration of Muslim workers in low quality jobs. The concentration of Muslim workers is relatively higher in self-employment (SE) and casual employment (CL), while it is lower in regular employment (RS).

Workers by the Type of Employment and Religious Groups, 2019-20

Nearly 40 percent of Muslim workers are engaged in self-employment, compared to 30 percent among Hindus. The high concentration of Muslim workers in self-employment is a reflection of their dependence on petty businesses in Muslim-concentrated areas. In fact, the low quality of self-employment is also confirmed by the fact that a large number of Muslim self-employed workers do not hire workers for assistance. Nearly 31 percent of the businesses among Muslims are run by the owners themselves. The low earnings reiterate their vulnerabilities, as it indicates that Muslim-owned enterprises are of low quality with low earning potential. In SE, the earnings are Rs 26509 and Rs 18649 for Hindus and Muslims, respectively.

The occupational segregation on the line of religious identity is also observed from the analysis, as diversification of enterprises is lower among them than among other religious groups. Out of the total enterprises, wearing apparel constitutes nearly 14 percent of the enterprises among Muslims, while this figure is only 5 percent among Hindus. This sector constitutes 48 percent of the total enterprises in the manufacturing sector among Muslims, while the corresponding figure is only 14 percent among Hindus. Muslim-owned enterprises are highly concentrated in retail trade as well. Nearly 32 percent of the total enterprises are among Muslims and 38 percent among Hindus, while the figure is 37 percent on an average in Delhi. The retail trade is also of lower quality among Muslims than Hindus which confirms the hypothesis that these enterprises are for survival only. This is evident from the fact that the share of retail trade in specialised stores is relatively lower among Muslims. Their share is higher only in food, beverage, and tobacco items which again reveals occupational segregation on the basis of religious identity.

Muslims’ share of regular employment is very low, and it further worsens in government jobs. Only 47 percent of Muslim workers are in regular employment, while this figure is 67 percent among Hindus. Nearly 5 percent of Muslim workers are engaged in government jobs, as against 12 percent among Hindus. The other religious minorities are also highly underrepresented in government jobs. In order to capture their underrepresentation, the number of Muslim staff in the central secretariat and ministry is counted. This is to note that these jobs are under the purview of the central government. Since these offices are located in Delhi, it will affect their socioeconomic condition notably. Out of the total 1,425 employees, only 1.8 percent are Muslims. There are no Muslim officers in 20 out of 59 departments. Muslims are highly represented only in the Ministry of Minority Affairs. Their representation among advocates on record and the police is also very low. Only 88 of the 2,328 advocates on record at the Supreme Court are Muslims, accounting for 3.78 percent of the total number of advocates on record. Further, a serious underrepresentation of Muslims is observed in the police department.

The most concerning factor with regard to the unemployment is that it is higher among the educated labour force than the overall rate and it is further higher among Muslims. The unemployment rate among secondary and higher education graduates is 13 per cent in Delhi. This figure is 22 per cent among Muslims as against 13 per cent among Hindus. This shows that merely improving the level of higher education does not improve employment opportunities particularly among Muslims. There is no denying the fact that poverty and lack of human capital are major factors behind such a state of affairs among Muslims. However, the fact that a similar level of education does not ensure a similar level of employment rate hints deprivation specific to the religious identity. Further, the low quality of employment can’t be attributed to the cultural and religious practices of the community as identity-based discrimination in employment can’t be ruled out. The existing studies, though few, show the prevalence of religion-based discrimination against Muslims.

The policies towards employment, at the national level and Delhi, rarely address the concern of backwardness of the Muslim minority. In 2021–22,the Delhi government allocated only 0.9 per cent of its total expenditures towards the welfare of SCs, STs, OBCs, and minorities, which is lower than the average allocation for SCs, STs, OBCs and minorities by states, 2.9% (PRS). The Delhi government has recently targeted employment generation through the Rozgar Budget for 2022–2023. The Rozgar bazar is another important initiative towards the creation of job opportunities. However, none of these initiatives put any special emphasis on the underprivileged groups.

Thoughthe empirical evidences provide compelling ground to sensitise the policies for addressing the vulnerability of the Muslim minority,the affirmative action targeting religious identities are generally ruled out on the pretext of secularism. However, such arguments fail to address the concern as to why religious identity can’t be a ground for affirmative action if the existing deprivation and discrimination are grounded into the prejudices directed towards a particular religious identity. Notwithstanding of the debate, the worsening socio-economic condition of Muslims vis-à-vis other groups is a reality. This gap is unlikely to reduce if Muslims are not provided level playing field through policy safeguards.

(Khalid Khan, Assistant Professor of Indian Institute of Dalit Studies, Advisor, Institute of Policy Studies and Advocacy, New Delhi- 110067)