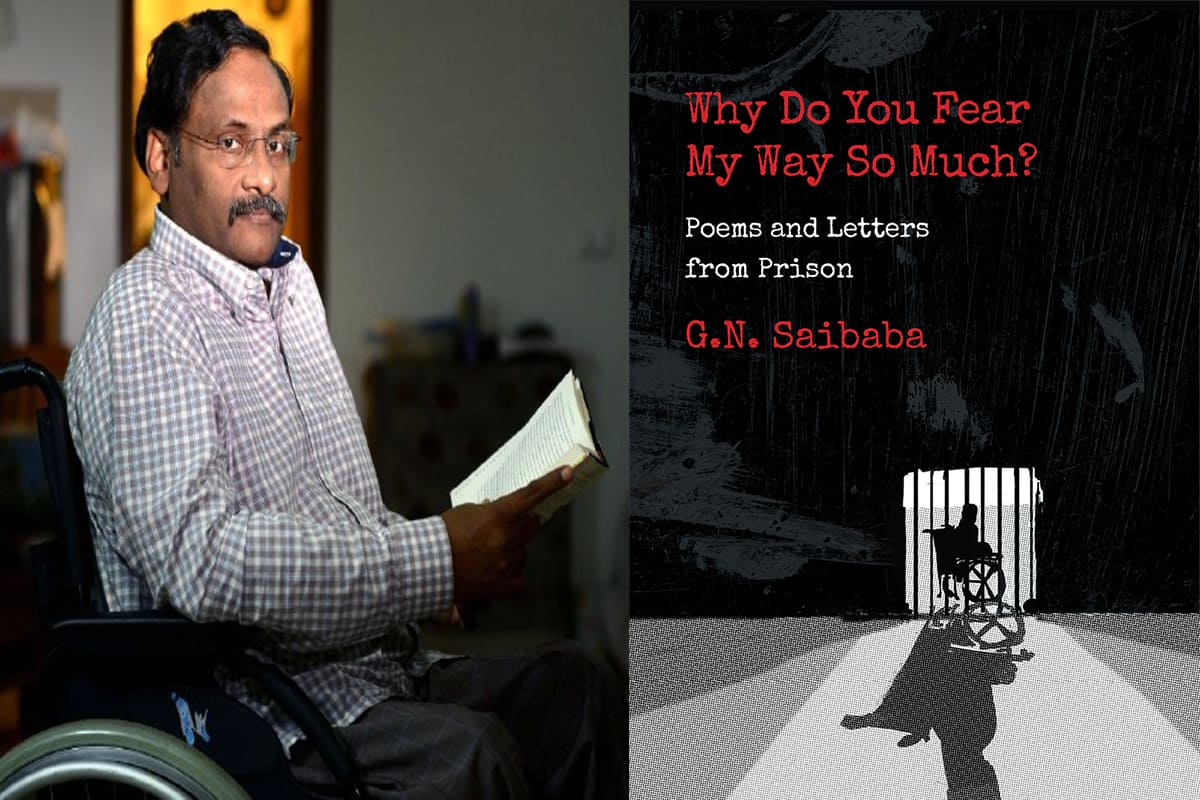

Two nights ago, I thought back to the time I skimmed through a 2018 Guardian article titled “Skim reading is the new normal”. As it always goes with google searches, an unexplained urge took over and pushed me to revisit the article. Right before I embarked on the Guardian article, I was reading (not skimming through) an advanced copy of GN Saibaba’s collected poems titled, “Why do you fear my way so much?” which I intended to review.

But essentially, the project I assigned to myself for a couple of hours was to take turns reading Saibaba’s poetry and deciphering how dangerous it would be if as the article suggested I, (or anyone else for that matter) skimmed through his poetry.

The Guardian article makes the case that with skim reading, “…we don’t have time to grasp complexity, to understand another’s feelings, to perceive beauty, and to create thoughts of the reader’s own.” While all these pursuits; of grasping complexity, perceiving beauty, and what not felt worthy of attention, it also pushed me to wonder what would be the perils of skim reading prison poetry. In this case, the perils of skim reading “Why do you fear my way so much?”

Delhi University professor and human rights activist GN Saibaba has been imprisoned in Nagpur Central Jail for his alleged links with Maoists since March 2017. He has been booked under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act. While in prison, he fought more than just 90 percent paralysis and loneliness and bit-by-bit wrote poetry to his wife Vasantha, his friends, and other loved ones. The volume of his poetry titled Why do you fear my way so much? was recently published by Speaking Tiger.

It would be arrogant at the least to presume to understand the inner workings of a man like GN Saibaba. Even trying to sift through his poetry, in an attempt to understand his psyche, is probably an exercise in futility. But it is an exercise worthy of our attention.

In the collection Why do you fear my way so much, Saibaba has written a letter to Anjum, a fictional character from Arundathi Roy’s The Ministry of Utmost Happiness. He writes to her to say:

“As days and months slip by in my solitary cell, I find that no one is interested any longer in reading my letters and responding to me… I suddenly felt that you are the only person who would really take my letters seriously and do something concrete for my freedom.”

It is unclear if the lines above are desolate and the musings of a now mistrustful man or if he finds a smattering of hope in writing to a fictional character he endears himself to. But either way, his reality of the anda cell (egg-shaped cell) is muted by his conversation with a non-existent being. This conversation at least to this reader feels like more than an exercise in creativity: it is intimate, an odd kind of healing. The kind that strips reality of any power to further oppress.

In a separate set of lines in a poem titled The Ocean is his voice, Dr Saibaba writes:

Its poetry, stupid

It’s stupendous poetry

It doesn’t need weapons

to smelt break the iron heels of history

Prison poetry or resistance poetry of any kind is a response to brute harshness with the use of metaphors and imagination. While seemingly futile, the use of imagination has generally been feared by the powers that be. In fact, Gauri Vishwanathan in her seminal work “Masks of Conquest” discusses how the Utilitarians and the Missionaries in colonial India, feared the introduction of poetry in the English curriculum. The concern expressed was that poetry would ‘result in affected style’ and ‘was harmful to morals’.

Back then, the idea of morality was a colonial one. Today, it still continues. However, the response to colonial cruelty as far as Saibaba is concerned is love and much like Kabir (the Sufi saint he invokes time and again), love requires struggle, it demands assiduous cultivation in order to overpower enslavement.

Listen to me,

O grievers,

The world of love takes shape

in your acts of struggle for it

Love is more than the simple tryst he shares with his wife, Vasantha. It is the aspiration for a better, more promising world. He makes it clear that all hearts ought to mourn each time there is barbarity. He also makes it clear that his heart does. In a poem titled Now we have more freedoms, he invokes Rohith Vemula, Perumal Murugan, and other heroes of oppression.

Despite his invocation of people dead and gone, letters to folks too distant or characters never to exist, Saibaba still struggles to speak to his beloved Vasantha. As Vasantha has remarked countless times before, Nagpur jail authorities refuse to let the couple communicate in Telugu, the language they know and love.

However, Saibaba’s love for his wife still shines through when he writes:

I read the expressions

on your face in the lines

when you scribbled them

inking your love

As does Vasantha’s response when she says:

“Here,

I will be again,

waiting for the wings of morning light

to pick up a bunch of warm rays

of hope with my wet eyelids.

But the love is chained, hindered by the glass windows of prison from which Saibaba and Vasantha talk in an uncomfortable language for twenty brief minutes. The professor’s desire to teach, to offer affection to his wife, his very physical health are all slowly crumbling away. In this context, skim reading his poetry would be more than just a regular danger. It would be more than just an inability to grasp complexity or understand another’s feelings.

It would perhaps be the most draconian thing a reader could do.