A week before India and Pakistan became independent dominions, the Nizam declared, along with a few other princes, that he would not be joining either nation. This was indeed something he was legally allowed to do under the Indian Independence Act but would be a catastrophe for India if ever successful. Nonetheless, the princes, longstanding allies of the empire, had to be let down gently, so under the leadership of Lord Mountbatten, a Standstill Agreement was signed between the two parties for a year. After a series of transgressions, arguably from both sides, the agreement broke down, and a month after Mountbatten left India, the Indian state invaded Hyderabad in a relatively bloodless military action that lasted less than a week. On 17th September, Hyderabad State officially became part of India. Since then, however, there has been confusion as to how to remember this event which continues to date. Was it liberation? Was it just integration? Was it unification? An analysis of the state’s history shows us why to call it ‘liberation’ leaves out the painful history of Hyderabadi Muslims.

Today, the only party which has been consistent with their policy on the observation of Hyderabad Liberation Day has been the BJP. The Congress had historically refused to hold elaborate big celebrations for September 17th. Ironically, the Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) was itself vociferous in its criticism of the Congress government of Andhra Pradesh during the struggle for a separate state, they failed to observe the celebrations as well. Since its rise to power, however, the party has retreated from this stance, giving rise to an odd situation: on 17th September, the BJP celebrates ‘Hyderabad Liberation Day’, while the TRS celebrates ‘National Integration Day’.

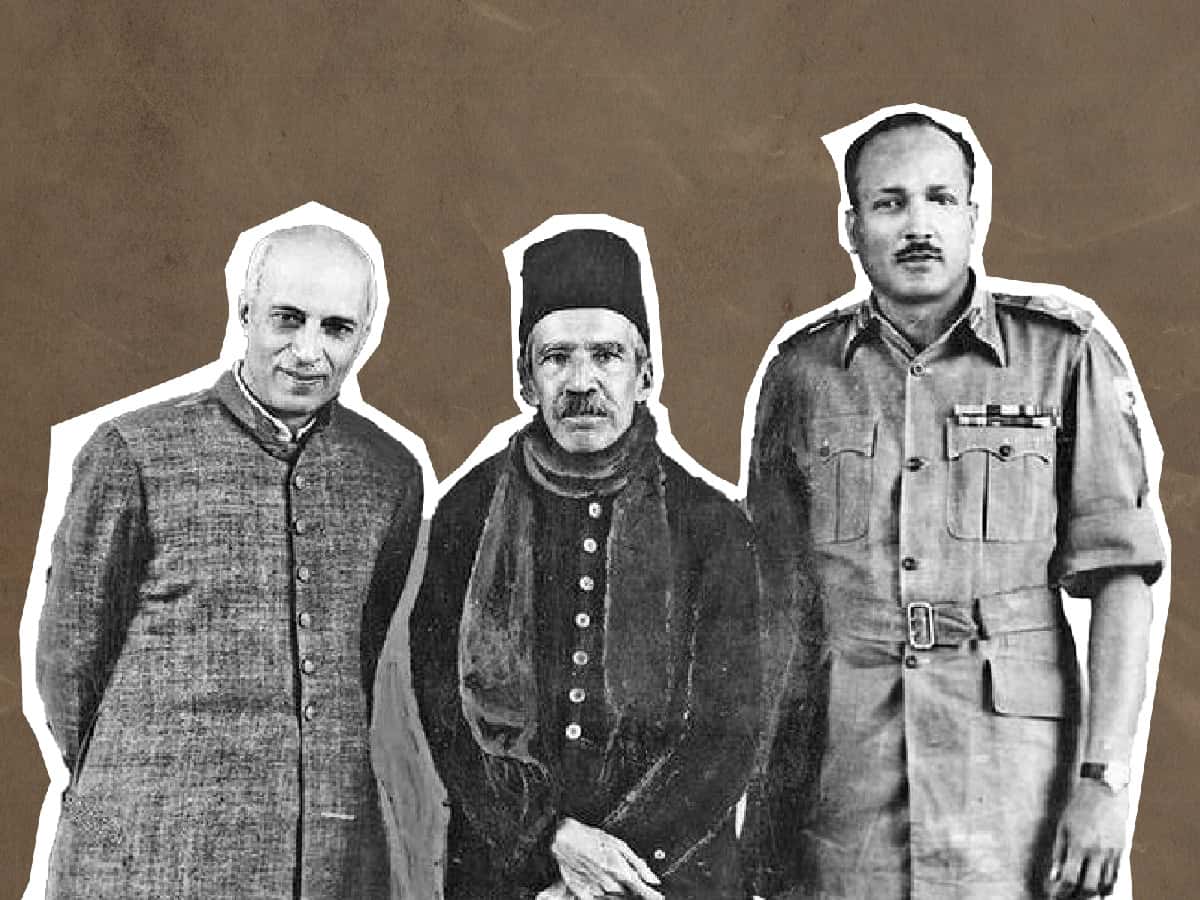

There may be several contemporary reasons why September 17 is not widely celebrated in Telangana, but possibly the biggest reason was that the freedom struggle in Hyderabad State was unlike that of the Indian National Congress. In Hyderabad, liberation had become deeply entangled in communal politics from the 1930s onwards the Hyderabad State Congress, formed in 1937, was not formally recognised by its mother body for years. Indeed, liberation was not always articulated in terms of colonialism, but in terms of religion. Parties like Arya Samaj, Rashtriya Swayamsevak Samithi, and Hindu Mahasabha, which were more powerful than the HSC ever was, fervently propagated that the Nizam and his rule had enslaved Hindus of the state. Indeed, after the Nizam abdicated, Sardar Vallabhbahi Patel wrote to the general in charge of the operation and congratulated him freeing Hindus of the state from years of bondage.

There was certainly an immediate context to this. In Hyderabad, the political party, Majlis Ittehad-ul-Muslimeen under a new, eccentric leader, Qasim Razvi, began encouraging civilian armed outfits to defend the Nizam’s state. At the time, this was hardly rare. Every political organisation – including HSC – had taken up arms in some capacity. Nationalists, encouraged by the Indian state, had even set up fortified villages along border areas from where attacks, raids, and robberies would be launched into Hyderabad. The Razakars’ activities were then encouraged by the Nizam and his police in fighting these dissidents — mainly communists in Telangana. However, a clever rhetoric was crafted by K.M Munshi, the agent-general of Hyderabad that they were after massacring Hindus. To a government that had still not emerged from the embers of Partition, this seemed more than plausible. The complexity of Hyderabad’s specific political context was ignored. A narrative was forged that Hindus were being specifically targetted and were living in constant fear

This history goes back even further. In 1938, the communal parties — RSS, HMS, and AS —launched a satyagraha for religious freedom in Hyderabad State. Over the course of a few months, more than ten thousand jathas (volunteers) poured into Hyderabad from Maharashtra and Karnataka. Ironically, while various horror stories flooded into neighbouring provinces, no major discrimination was observed by the satyagrahis. Indeed, the Nizam himself was hardly a typical Sunni, and, as is customary for most royal families in the subcontinent, paid his respects to other religions as well. In less than a year, the fanfare faded and people lost interest in the satyagraha. The narrative, however, seemed to have survived, and when the country became engulfed in the flames of Partition, it became the perfect fuel, leading to what was possibly the bloodiest communal massacre in Hyderabad.

In the popular public imagination, the story stops with September 17th, but that is not true for everyone. In the months following, as a senior member of the Congress, Pandit Sunderlal and his team reported that an estimated 27,000-40,000 Muslims were massacred in Hyderabad by incoming right-wing Hindu mobs and the Indian army. There was a near exodus of Muslims from the countryside after this, and although there exists a general dementia of this part of history, this event is remembered as a great tragedy in Muslim families of former Hyderabad State. Nearly 13,000 Muslims suspected to be Razakars were imprisoned in the next two years, most of whom were released. Although we rarely acknowledge how the Partition affected the South, Hyderabad had become the ‘third front of Partition’, as Sunil Purushotham writes in his book, From Raj to Republic.

Muslims of Hyderabad, and of the country, continue to face the repercussions of this history in a plethora of ways. The act of calling it ‘liberation’, therefore, is a highly weighted choice, and one that is not without the same divisive tactics that the BJP has employed countless times. The tragedy of Hyderabad has been that the region’s princely history has never found its place in our political discourse and hence threatens to slip into oblivion. As long as we keep ignoring the complexities of our history in favour of white-washed, nationalist narratives, we are hindering our own recovery.

Tanvi Rupakula has done her BA from Ashoka University and wrote her undergraduate thesis on Nizam’s bid for independence.