I first learned about Zafar Agha through his stories in India Today magazine in the 1990s. Since I had begun reading newspapers and periodicals voraciously, India Today too figured in the list of publications I devoured regularly.

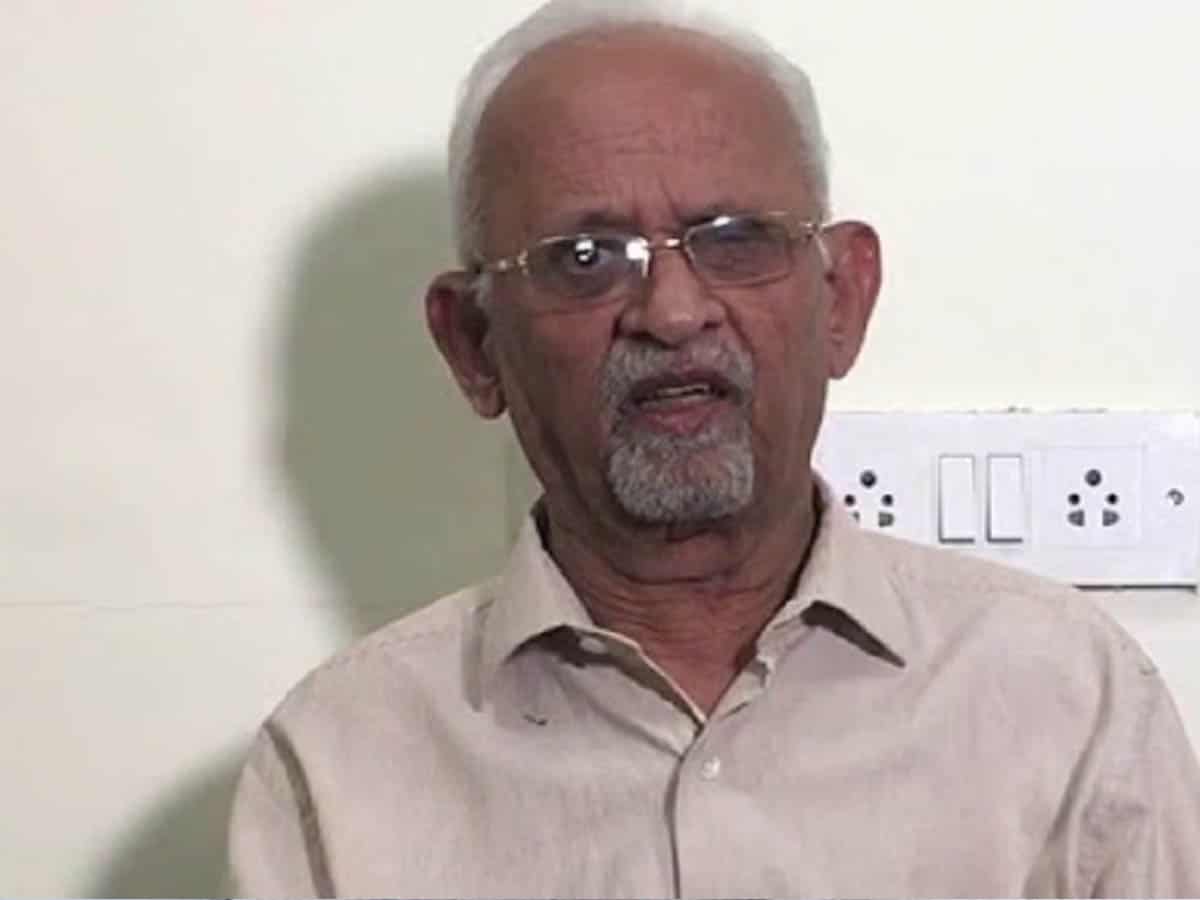

Zafar Agha left us on the morning of Friday (March 22, 2014). He was 70.

Having been uprooted from Aligarh and planted on the bank of the Ganga in Patna in 1988-89, I would visit Maulana Mazharul Haque Library located at the sprawling campus of Sadaqat Ashram, the Bihar Pradesh Congress Committee’s headquarters near Kurji, not very far from where I lived.

Every afternoon I would walk down to the old library’s reading room where a group of young boys and girls, mostly preparing for competitive exams, would pore over newspapers and magazines. I would grab India Today (English), then a fortnightly, and try to read everything that appealed to me. Outlook has not been baptised yet and India Today commanded its leadership in the English magazines market.

Tarun Tejpal’s essays (what a misfortune befell on this brilliant writer, my Lord), Zafar Agha’s political reportages and comments and Farzand Ahmed’s dispatches from Patna were some of the contents in India Today I never missed. Having been schooled in Hindi medium, my English vocabulary was terribly poor. To build it up, I would carry a pocket dictionary and write the words that seemed unfamiliar to me and look up their meanings in the dictionary. I also remember I had a small notebook where the new words with their meanings entered so that I could go back to them later. This helped me build up my vocabulary robust and a little more respectable.

I met Zafar Sahab later in his journalistic career. Much after he had finished playing some glorious innings. It was a summer afternoon around 2013 or 2014 when I received a call from him. He would write regular columns for Inquilab Urdu daily. I think he had not joined The National Herald as its chief editor then. He had read my piece on Indian Muslims and the way they were targeted by the agencies. Hardly a fortnight went by when a Muslim was not found to be involved in a terror act somewhere in the country.

Thank God, we do not hear today much of the activities or about the “sleeper cells” of Indian Mujahedeen, if at all it existed or exists.

Zafar Sahab, over two decades older than me and miles ahead in experience and maturity, appreciated my writings and told me to see him next time I was in Delhi.

After some time, I happened to be in Delhi and he invited me to his office. He showed me around the Herald office and the work they were doing. Having been revamped after years of remaining in hiatus, the Herald was available only online. Its print avatar was still a few years away. His peon brought hot samosas and tea for us. After an hour or so, he came out to see me off and told his driver to drop me off at my hotel. I was overwhelmed with his gesture and the love that he had for juniors.

The second time I met him was at Ahmed Patel’s office in Lutyens Delhi. Zafar Sahab commanded huge respect among Congress leaders. Over a dozen political activists and party men from across the country waited for an audience with Patel. Lok Sabha elections of 2014 were due, and many were there seeking tickets. Patel, political secretary of Sonia Gandhi, was so powerful that, it is said almost nothing reached Madam Gandhi without getting filtered by Patel.

As soon as Patel heard that Zafar Agha was in the waiting room, he sent a message to bring him in. Zafar Sahab, a friend and I were ushered in. We stayed there for 15 minutes and, while leaving, Zafar Sahab again took promise from me to meet him soon. Alas, that never happened though we spoke on phone a couple of times.

When my book Aligarh Muslim University: The Making of the Modern Indian Muslim came, I sent him a copy. He liked the book and was kind enough to publish some excerpts in the National Herald.

Zafar Agha was among the last of the representatives of old school of journalism. A progressive and secular to the core, he had his fingers on the pulse of India’s politics. He had witnessed and covered many ups and downs and chronicled some of the stormy episodes of post-independence Indian history.

He had covered Ram Mandir Movement which culminated into the demolition of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya and widespread riots in its aftermath. He told me a shocking story about a big Muslim leader who had bartered and damaged the Babri Masjid issue in lieu of a huge personal favour. I could believe him because Zafar Sahab had no reasons to lie as nobody could buy him nor was he after power or pelf at the end of his journalistic career. I returned with a heavy heart, thinking how some people could sell their imaan just because of some personal gains.

As I returned from Agha Sahab’s office, a couplet by late Saiyyid Hamid, retired Civil Servant and VC of Aligarh Muslim University, poet-scholar and stylish essayist in Urdu, played on my mind:

Ek do zakhm nahin, jism hai sab chchalni

Dard bechara pareshan hai kahan se utthe

Zafar Sahab was a noble soul. He was hugely concerned about the deteriorating Hindu-Muslim relationship as well as erasure of India’s celebrated multiculturalism.

Aisa kahan se laayein ki tujhas kahein jise

Zafar Agah, you will be missed for long. RIP.