By Dayem Mohammad Ansari

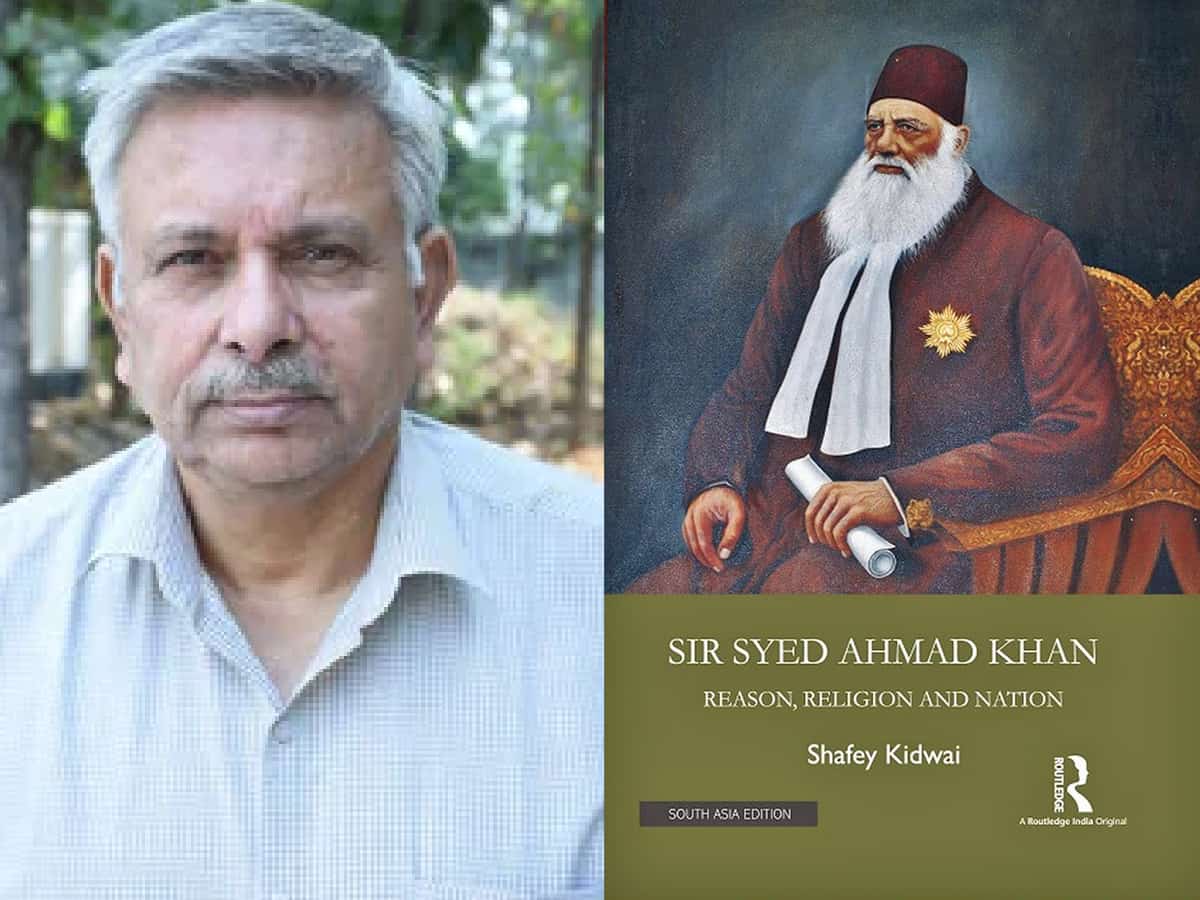

The acumen of Shafey Kidwai doesn’t let him stay where the road ends. The seeker inside him not only jumps over the ditch but also succeeds in finding ground. His recent work Sir Syed Ahmed Khan – Reason, Religion and Nation (Routledge, 2021, South Asia Edition) establishes him as an authority over the life and works of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, one of the pioneers of modern India. In his work, Shafey not only explores the life of Sir Syed in a novel way but also presents several facets of his (Sir Syed’s) life which have remained incognito till this book is inked. This valuable document brings Sir Syed’s legacy beyond education and politics to us, an aspect which often eludes those who write on him.

Designed in six chapters, this books deals with almost all the aspects of the life of the legend. Ranging from ‘biographical narrative’ to ‘intellectual awakening through periodicals’, it contains all the shades of Sir Syed. Though this brief review is hardly measured up to highlight the significance the book fully, some random extracts from it can be taken to underline what gives a distinct flavor to the book.

In the first chapter ‘Biographical Narrative’, the author explores, discovers and presents before us that after suppressing the Revolt of 1857, the British government in October 1886, constituted a 16 member Public Service Commission which was set up with the purpose to revisit its administrative structure.

Along with other eminent names of the panel, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan was also included therein. While writing this, the author clarifies tha: “The Commission was set up in 1886 not in 1887 as mentioned by Hali.” (p. 40)

Khawaja Altaf Hussain Hali (1837-1914) was among the initial biographers of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan. His celebrated work, Hayat-e-Javed (1901) narrates the life of Sir Syed at great length. Yet, despite its historical importance, one cannot accept everything written in the book. So does Shafey. He doesn’t rely on the incidents mentioned in this book and after much corroboration; he rectifies the century old errors.

As we are passing through these testing days when all the institutions are under scathing attack by the right wing and the values of this great country are being buried deep under the mother earth, the life of Sir Syed appears a fascinating example for us. Shafey rightly remarks: “For Sir Syed, religion was a matter of personal choice, which had to be protected, and any violation of it would be an affront to human dignity. He lodged a strong protest whenever it occurred.”

In the third chapter, “Unravelling Sir Syed”, the author discusses all the issues on which Sir Syed spoke and did fight. From Blasphemy to Conversion, from Jihad to Cow Sacrifice, or Freedom of expression to Gender Equality, Sir Syed not only dealt with a range of issues but in most of them he succeeded in maintaining his observations.

But it is the fourth chapter (Female Education) which can be seen as the defining area of the book where the author broadly and boldly discusses the thoughts and ideas of Sir Syed. Being a judicial officer –cum-educationist, nationalist and philanthropist, the personality of Sir Syed was not easy to read and decipher, hence his opponents had leisure and luxury to malign his image which includes the remarks like someone who ‘strengthening the patriarchal society’, ‘an ignorant of the rights of the women’ and an orthodox who ‘doesn’t favor female education’ etc. A host of people (such as Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah, Gail Minault, and David Lelyveld etc.) sharply criticized Sir Syed’s views on female education. For instance, while narrating the meeting of Maulvi Syed Mumtaz Ali with Sir Syed where the latter wanted to show him the manuscripts of his (Mumtaz Ali) treatise in defence of women’s rights in Islam (Huqooq-e-Niswan), Gail Minault described this as an event which shocked Sir Syed ‘and his face turned red’ and ‘he tore up the manuscript and threw it in the waste paper basket’. David Lelyveld, while endorsing this episode, points out that “Mumtaz Ali’s manuscript left Sir Syed so upset that he decided not to let it get published. Sir Syed did not want women to go beyond their duly assigned role of maintaining household affairs, and he hardly stood for the political, social, and religious emancipation of women.”

The author says, “It is indeed difficult to excavate the truth from the heap of lies with questions which attack the credibility of Sir Syed like; ‘Did Sir Syed tear up the manuscript? Did he take a rigid stand against women’s education? Did he ever make up for it?’ But despite knowing the fact that there is dearth of accurate information on this subject, Shafey doesn’t let him stop where the line ends, and after sinking in the sea of various testimonials and other narratives, and corroborating several other evidences, he finally discovers the shining pearl of truth. Shafey maintains that while initially Sir Syed was neither seriously concerned for female education nor was he actively engaged in promoting it, especially for the Muslim women (as he used to advance pseudo-socio-religious arguments to reinforce the legitimacy of tradition earlier), but he was not strictly opposed to it either. In due course, Sir Syed was gradually convinced by the people and the circumstances that the concept of women education was inevitable and it was bound to happen someday or the other, and for this he must not only propagate and advocate for it but also promote it at his own level. However, he took his own time for this. Initially, he (Sir Syed) endorsed “home based education with gender segregation, and his concept of female education seemed to be inspired by a mindset that hardly pays heed to liberal values central to a plural society. For him, female education is to be preceded by certain preconditions, but the highest priority should be accorded to purdah.”

But in 1869, a visible change was noticed in Sir Syed’s attitude when The Aligarh Institute Gazette cast off purdah as a sacrosanct concept by describing female education as a national necessity. Though it did not criticize the concept of institutionalized female education, yet it pleaded to monitor what is being taught at girls’ schools. Personally, Sir Syed always argued of tutor-based home education for girls and for him, every attempt of popularizing women’s education is destined to fail, no matter how well-intentioned it looks but soon he was proved wrong and he was made to change his mind. And the author submits that it is the area of promoting female education where we find Sir Syed on shaky grounds as he was always reluctant in admitting the fact that regardless of religion, female education was a necessity without which the Muslim Community could not achieve complete progress. He remained unconvinced that tutor-based home education for the Muslim girls was an out dated thought which serves no purpose to anyone. And that’s why, despite his tall image as a reformer of the Indian Muslim, Sir Syed appears as someone who (as David Lelyveld sums up) ‘articulated the dominant male ideology of his times.’

On concluding note, I must differ with this remark that “This book presents a nuanced narrative on Sir Syed Ahmed Khan’s life.” This book not only explores the life of Sir Syed from a different lens but also excavates many findings which were remained unknown to us till date. The scholar inside Shafey Kidwai undergoes through rigorous pressure while drafting this book. He not only revives and rejuvenates the study of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan but also injects in it the enthusiasm to dress in Sir Syed’s clothes and to live and think in his way. What else can be the success for an author if he transforms his readers into his book?

Dayem Mohammad Ansari’s E-Mail: dayemansari68@gmail.com and

Mobile number 8777834566