By Y Laxmi Samhita

Over the past few decades, there has been an increasing gap in the population growth rate of the states in Northern and Southern India. This disparity has raised questions of over-representation and under- representation of states in the Lok Sabha. This article tries to understand how the increasing population in a few states influences the allocation of seats in representative bodies and the challenges raised by its implications for seat redistribution.

Article 81 of the Indian Constitution defines the composition of the Lok Sabha; the Lok Sabha should have a maximum of 550 elected members, with a provision for up to 20 representatives from Union Territories. It further specifies that the allocation of Lok Sabha seats to each state should be determined in a manner that aims to maintain a consistent ratio between the number of seats and the population of the state to the greatest extent possible. Similarly, the US Constitution mandates congressional reapportionment every decade, allocating seats based on each state’s proportionate share of the total population. This means that each state receives the number of seats in the House of Representatives, reflecting its relative population size. Additionally, every state is constitutionally entitled to at least one seat in the House and two seats in the Senate, regardless of population size.

In India, the delimitation process has been frozen since 1976. The 42nd Constitutional amendment during the Emergency established that the values of the 1971 census would remain valid until the next census after 2000. A similar provision was added to Article 82, halting the readjustment process until 2000. The 84th Constitutional Amendment in 2001 extended the deadlines to 2026, justifying it with the National Population Policy and family planning progress. A delimitation exercise based on the 2001 census occurred from July 2002 to May 2008, readjusting all parliamentary and assembly constituencies. However, the freeze prevented an increase in the total number of seats in the Lok Sabha.

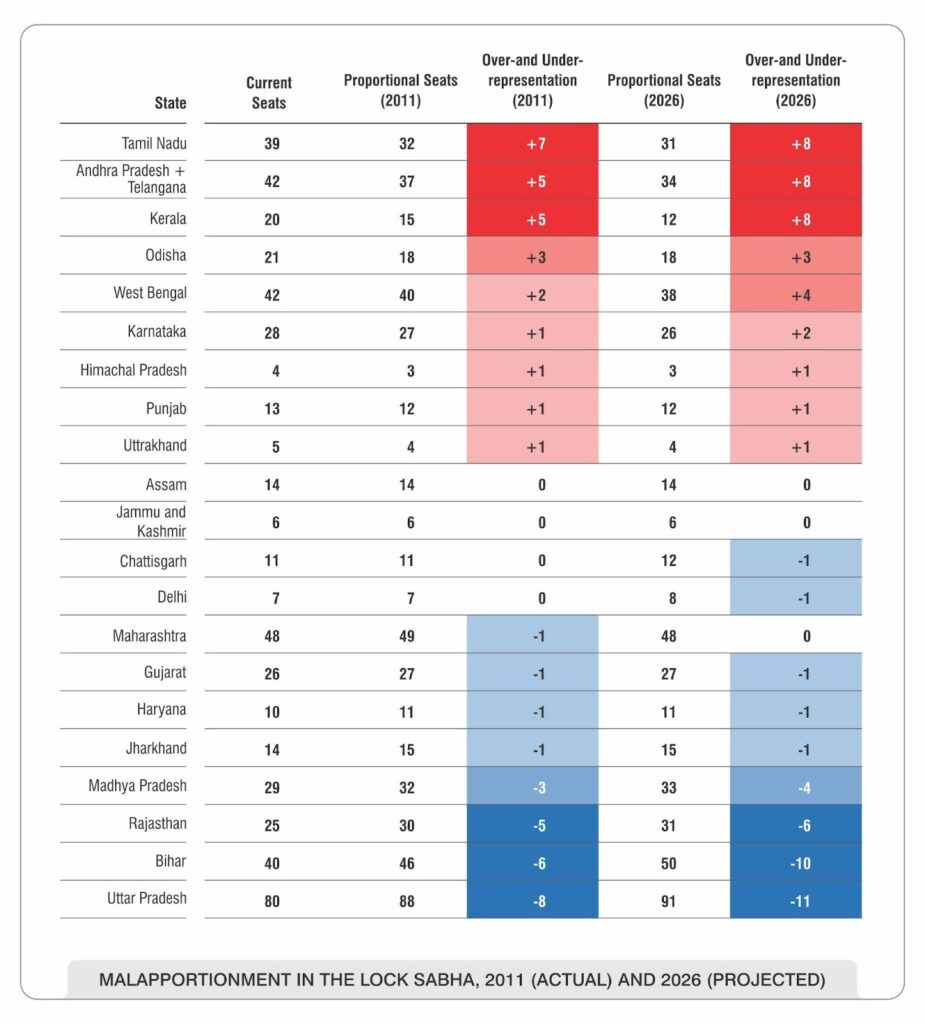

Alistair McMillan, a political scientist, previously documented significant discrepancies in over- and under-representation in India’s Lok Sabha. His calculations based on the 2001 Census revealed that Tamil Nadu should have had seven fewer seats, while Uttar Pradesh should have gained seven more seats than allocated.

To further highlight the disparities, Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson updated McMillan’s calculations using the 2011 Census figures. Using the Webster method, a reliable formula for unbiased seat allocation, the study projected state population figures up to 2026 based on data from both the 2001 and 2011 Censuses. The analysis illustrated even more severe malapportionment issues that could persist beyond the reapportionment freeze. The revised seat counts for each state showed significant differences, with certain states being underrepresented and others overrepresented.

By 2031, when the next decennial census will take place, the data used for Lok Sabha seat distribution will have been six decades old. Thus, if the delimitation exercise takes place, it will cause a considerable shift in the number of seats allocated to each state, with southern states losing seats to the northern states with larger populations. States in the South could lose as many as 24 seats, while those in the North may gain more than 32 seats.

Additionally, this exercise may strengthen parties with northern strongholds. States like Kerala and Tamil Nadu in the south, with slower population growth, argue against penalisation for effective population management compared to high-growth states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in the North. Some view it as unjust that states implementing family planning measures are penalised while others are incentivised with a different approach. Conversely, northern states claim unfair treatment, citing the importance of “one person, one vote” in democratic representation.

The delimitation exercise will impact the allocation of seats for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (SC/ST) in each state. Adjusting figures to align with the 2011 Census data would result in a minor change, with 1 additional seat reserved for ST and 2 for SC. However, this adjustment reflects a noticeable regional shift: states in the southern region, with slower population growth, will have fewer reserved seats, while states in the northern region, with faster population growth, will gain more seats. In total, the reservation status of 18 seats will change.

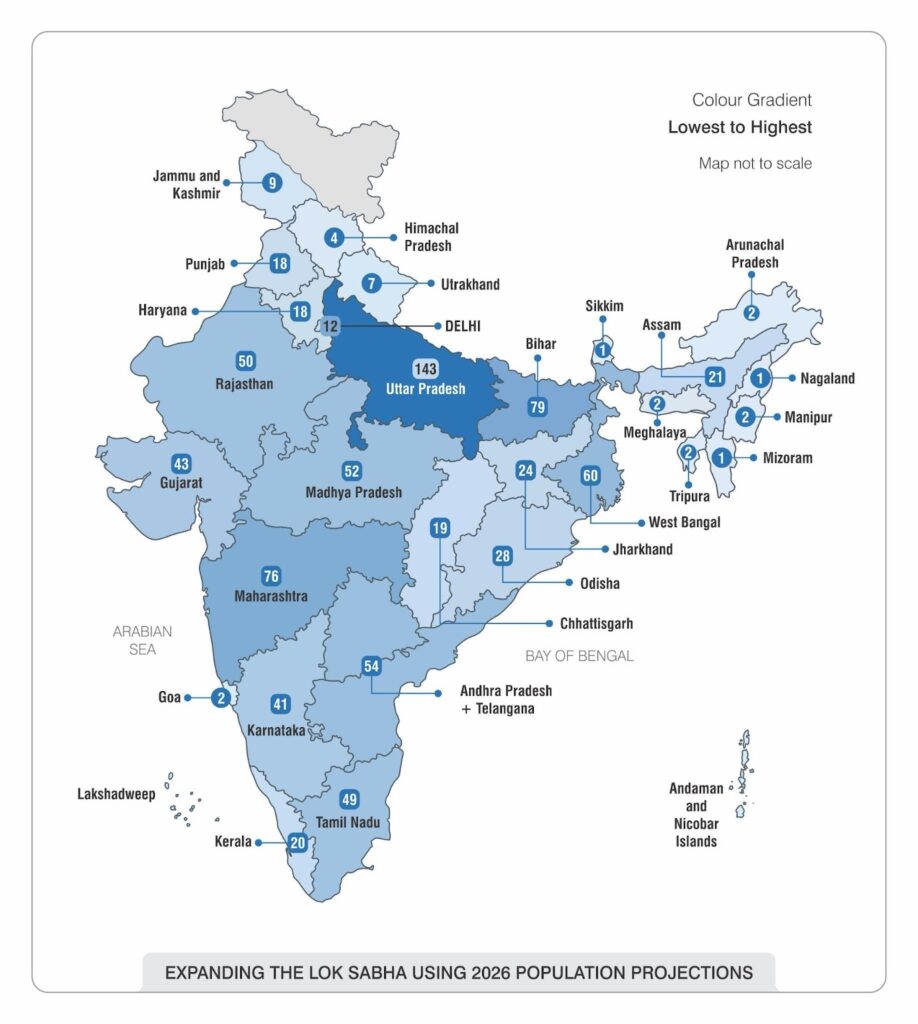

Despite the challenges, Vaishnav and Hintson argue that the reapportionment exercise must not be further delayed. They propose two solutions to address the drastic shift during reapportionment. The first strategy is to increase the number of seats in the Lok Sabha. This approach offers two benefits: more efficient governance with MPs representing smaller constituencies, and it’s politically viable as politicians are more likely to agree to increase seats in specific areas rather than giving up seats in influential regions. To avoid any state losing representatives, the maximum Lok Sabha strength must be increased to 848.

Their other solution involves reforming the composition of the Rajya Sabha, which has deviated from its intended purpose as a platform for states’ representation, with non-residents holding seats representing states.

No matter the route taken, it is imperative for the delimitation exercise not to be delayed after 2026 so as to tackle the problem of malapportionment in the Lok Sabha. The crux of the problem deals with representation, especially the widening rift between North and South. This dialogue must be a part of the larger conversation about India’s democratic federalism; the centre and the states must take this opportunity to discuss other issues that address interstate inequality. Missing this opportunity would pose the risk of causing additional harm to India’s federal structure, which is a crucial component of India’s democratic system.

Sources:

• Article 81: Composition of the House of the People. (n.d.). Constitution of India.

• Pollard, K., & Mather, M. (2020, February 19). U.S. House Seats Are Shifting South and West Based on Population Changes. PRB.

• Mandhani, A. (2021, July 30). Lok Sabha strength to be increased to 1,000 from 543? Here’s how it can be done. ThePrint

• Lahiri, I. (2022, December 29). How census-based delimitation for Lok Sabha seats could shake up politics & disadvantage south. ThePrint.

• Vaishnav, M., & Hintson, J. (2019, March 14). India’s Emerging Crisis of Representation. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Y Laxmi Samhita is a Research Intern with Centre for Development Policy and Practice, Hyderabad