Perhaps all the dragons in our lives are princesses who are only waiting to see us act, just once, with beauty and courage. Perhaps everything that frightens us is, in its deepest essence, something helpless that wants our love.

— Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet, 1929

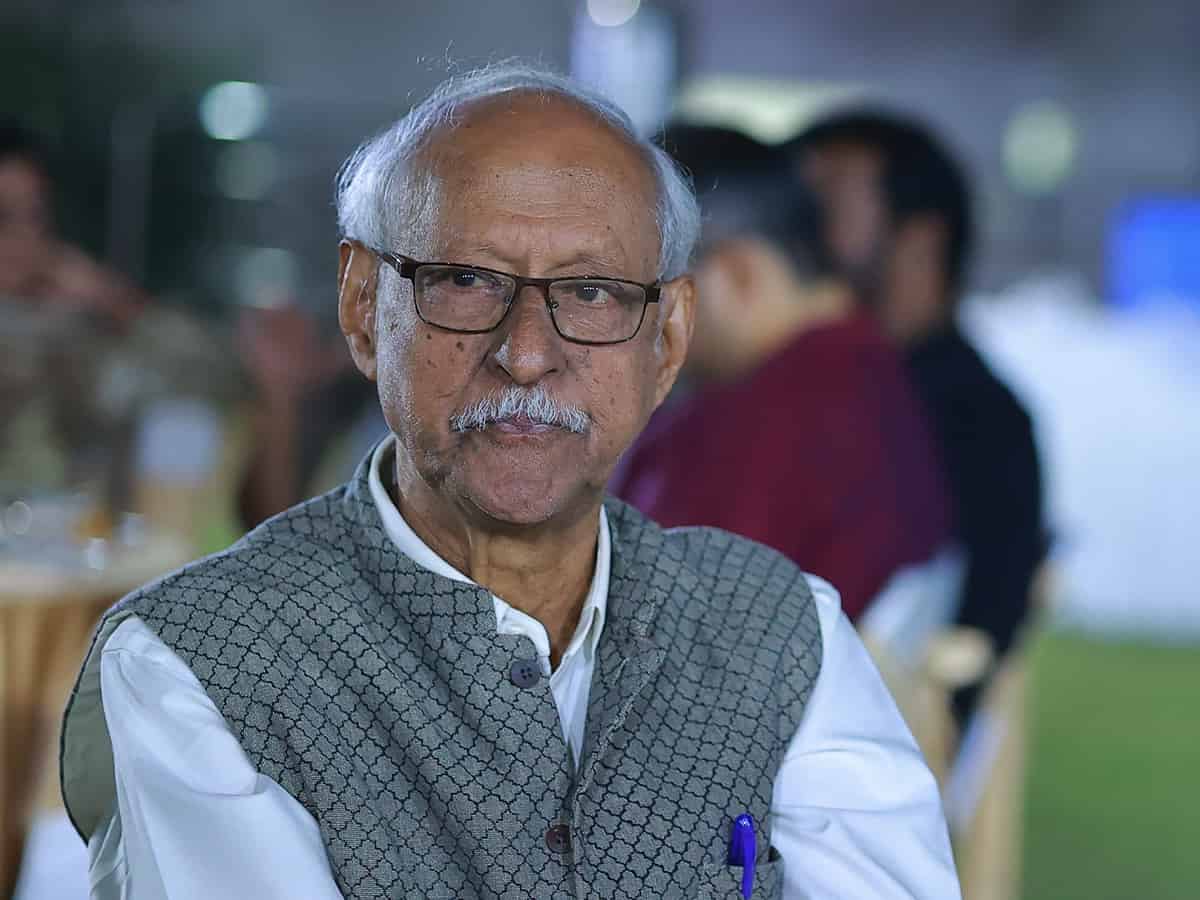

In the age of anxiety and overlapping narratives, the voice of dissent often echoes anger. However, unwavering resistance to oppression of any kind can succeed only through dialogue; one that is embedded in clarity and empathy. Jnanpith awardee, and short story writer, Damodar Mauzo is a quintessential representation of the above idea.

Mauzo’s notable works include Ganthon 1971, Karmelin 1983, Tsunami Simon 1996, Teresa’s Man and Other Storiesfrom Goa 2014, and The Wait and Other Stories, 2022. Mauzo’s stories are inspired by the everyday life of regular Goan men and women. His voice is fearless and kind, sharp and pervasive. In a career spanning more than sixty years of writing, Mauzo has received numerous literary accolades. His works have been translated into more than fourteen languages. Mauzo was invited to the Hyderabad Literary Festival, (January 27-29), Hyderabad as the Chief Guest. ‘Konkani’ was the Indian language in focus.

I had the opportunity to spend an evening in the pleasantly gentle company of Damodar Mauzo and his spouse Shaila Mauzo.

Literary festivals, throughout the day, are expended in a frenzy of talks, performances, and readings. The nights are spacious. In a Joyce Carol Oats-way, at night, only the lamp lights the page of the book and the outside world becomes ‘deliciously small.’ In the noir wakefulness,words become what they cannot in the day. Thus, meeting an author under starlight was an assured route to a lush conversation.

At night, writers are hungry—both for food and genuinely interesting conversations. At a table graced by the likes of Damodar Mauzo, journalist P Sainath, academic Sonya Gill, and literary enthusiast Dr. Sunita Reddy, the constant flow of ideas, arguments, and questions was inevitable. The poet in me was drawn toward Damodar Mauzo. He queried about my poems on the pandemic.

We briefly discussed the poem, Under the Peepal Tree, which is based on the experiences of Covid-patients who lay under Peepal trees believing that they would receive a constant and inexpensive flow of oxygen. I expressed my dilemma of balancing the purpose and aesthetic appeal of the poem. I invest hours trying to decipher if the troubled idea of the poem is artistic and effective enough to trouble the reader. Did the poem act as a bridge? I ask. Is there a reader waiting to resonate with the words of the writer? I wonder.

Mauzo’s answer was an emphatic dismissal of self-doubt. “One must say what one has to say,” said Mauzo. All work is ‘work-in-progress’ and a writer will eventually get there, but there’s no point in continuously scrutinizing one’s writing for the sake of the reader. Often writers themselves are the biggest suspect of their own talent. Mauzo believes that one needs to swim out of the tides of disbelief and dedicate time to sustained writing habits, without expecting rewards. This is the only way a writer can produce his or her best work. This would also mean a possible dissociation from a salaried job or a business. A string of questions shaped our conversation. “Would it be possible to have a policy that would recognize writers and poets as full-time professionals?”

“Would academic institutions open up posts for writers with a steady flow of scholarship or stipend?”

Mauzo, like all good writers, is hopeful. He believes that a healthy writing culture, including constructive literary criticism, will grow in the future.

Apart from being a prominent literary figure, Damodar Mauzo is also an activist. He has strived, for years, to preserve the cultural distinctiveness of Goa. His life as a public intellectual, a preserver, and a seeker of knowledge revolves not only around literary personalities but common people at large.

Shaila Mauzo shared details about her everyday life; the gradual transition from the fast-paced mandates of Mumbai to the relaxed spirit of Goa. I am often curious about the respective partner of a writer or an artist. How do they fit into the hectic hustle? Shaila Mauzo’s answer was simple, “I have always enjoyed my own routine; family, children, and the shop.” She understands that her partner requires isolation. Hence, they both insist on spending quality time with each other, even if it is for a brief period. This has been the key to their partnership; their love for Goa and a home that smells like Goan fish curry.

The evening gradually transmuted into a cold, dew-drenched night— yet warm with laughter and conversations. My peripatetic thoughts on literary pleasure and purpose reflected on the broader question of the individual we become in our pursuit of a career in writing. Popular culture has often celebrated artists as abandoned geniuses, blowing smoke rings into the air; glamorous bohemians who are consumed by rootless experiences of emotional and physical diversity. This is true but domestic belonging is also true. Often, when I swing between my purpose as a full-time academic and the pleasure of writing poetry, I evoke unsettling thoughts. However, now I can seek stasis; knowing that routine spaces can summon creativity; that a writer, whether in isolation or always accompanied by a loving companion, may be blessed with the ‘milk of paradise’; palms that hold the pen in writing retreats or issue receipts in a shop, may equally birth despair and nurture on the bird-rocked sky of imagination.