By Arman Hasan

In contemporary India, one of the greatest material challenges for urban planners has been to comprehend the trends of socio-spatial marginality in the city.

Hyderabad is no exception to the pattern of increasing religious exclusion and marginalisation produced within urban environments. In everyday academic and journalistic literature, this phenomenon is called “ghettoisation.”

But there exist multiplicities of nuances when it comes to the study of “ghettoisation” in terms of quantitative analysis of the spaces in which one community is confined, the location of the agency involved in that confinement, and the more extensive socioeconomic structural processes which produce the discourse of that location.

News outlets have been reporting on the phenomenon of “Muslim ghettos” and spatial exclusion; however, it is imperative to be conscious when one is attaching terminologies that have a history marred with stigmatisation.

The most basic nuanced definition of a ghetto is developed by Loïc Wacquant, who proposed through the critique of the Chicago School of Urban Sociology that a ghetto is “a bounded, ethnically [relating to social identity, for example, religion] uniform socio-spatial formation born of the forcible relegation of a negatively typed population.”

The term “ghetto” emerged in medieval European cities where the Jews were confined in certain localities while being allowed to perform economic activities across the city. The term became popular in the 20th century when scholars began studying ethnic localities in urban America where migrants formed homogeneous spatial confinements while producing “close cultural” proximity spaces.

Scholars began questioning the terminology of ghettos and their agentive desires to live with people from the same community because, unlike the Jews, it wasn’t emerging out of ostracisation and forced relegation on the part of the discrimination experienced in the city. Thus, emerged the literature on Black ghettos in America where Blacks were forced to live in relegated spaces of the city purely because of their race.

Bringing this history here is important because of the context of the Global North and the debates that ensued on the terminologies that determined the litmus for studying social segregation across the cities in the Global South.

The Sachar Committee discourse, which highlighted the conditions of socio-economic marginalisation of Muslims in India, briefly mentioned that “fearing for their security, Muslims are increasingly resorting to living in ghettos across the country.” While this highlighted the contextually defined “desire” of Muslims, nonetheless, to call it agentive is also a contested idiom.

Building upon this, Christophe Jaffrelot and Laurent Gayer proposed that there are five things to keep in mind while studying the phenomenon of Muslim ghettoisation in India; the residential constraint over a population, the social diversity of the localities, the neglect by the state authorities in such neighbourhoods such as lack of infrastructures, educational facilities, etc; the estrangement of the space from the rest of the city; and the general sense of closure for the people here from the rest of the city.

While theory can be a good starting point for studying the urban marginalisation of Muslims in India, it is the subjective nature of cities that makes them more diverse and nuanced in their experiences. Hyderabad is an ideal example.

As Raphael Susewind has pointed out, Hyderabad is the exception of a split case of segregation in the city, where the inner administrative region shows an index of dissimilarity level of 0.42 out of 1 (meaning 42% of Muslims must exchange places with other communities in the city for even distribution across the space).

However, the Greater Hyderabad environment, which involves the larger densely inhabited region around Hyderabad, shows a very stark picture, with an index of D (M) 0.51 (meaning that 51% of Muslims must exchange places with other communities in the city), showing that Greater Hyderabad is more segregated than even cities like Delhi.

The second problem in such data aggregates emerging through their influence of the urban theory from the Global North is that it produces spatial segregation without considering the subjective desires of the people involved in choosing to live separately.

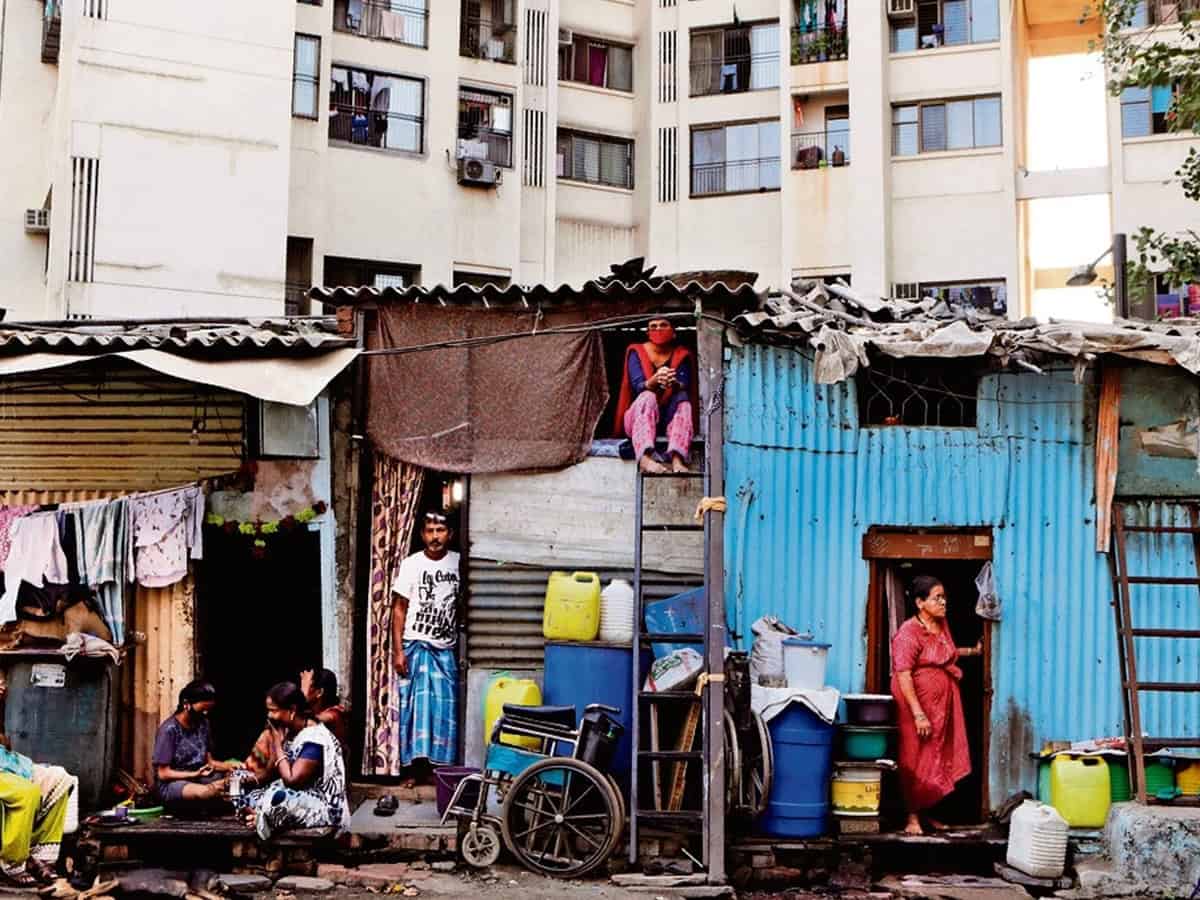

As reported by the Hyderabad Urban Lab, Muslim neighbourhoods, especially those in slums in the city, are the worst off in terms of economic, housing, and infrastructural conditions. As a result of greater communal violence across the city and rural-urban migration seeking safe conditions, these spaces also play a fuzzy role, where they become sites where people can acquire networks of connections, friendships, and social capital through which people find work in the informal economy.

As a historical comparison, the same was suggested by Drake and Clayton in the 1940s in Chicago, the city where urban theory emerged that Blacks developed a parallel urban landscape within the city where ghettoisation also played the role of a safety net against broader urban segregation. However, this does not imply advocacy for more segregation, for the Black spaces in contemporary America have become sites of extreme police patrolling and marginalisation, which Wacquant now calls hyper-ghettos.

One must avoid studying “ghettos” as merely a spatial phenomenon. I concur with Wacquant that ghettoisation is equally an economic and structural phenomenon in the cities of India that plays complicated and contradictory functions, requiring more detailed analysis than stigmatised rhetoric making.

At the same time, we must incorporate a policy perspective in dialogue with ethnographic exploration to make sense of what people mean by ghettoisation. The government only provides data on the total religious demography of the cities but not on degrees of segregation within the localities of the city. We need data that let us first recognise what is happening and bring into dialogue the meaning of ghettoisation from the people’s perspective and planning.

Arman Hasan is a postgraduate researcher. He has recently completed a master’s degree in Sociology from South Asian University, New Delhi. Currently, he is working for the Centre for Development Policy and Practice, Hyderabad.