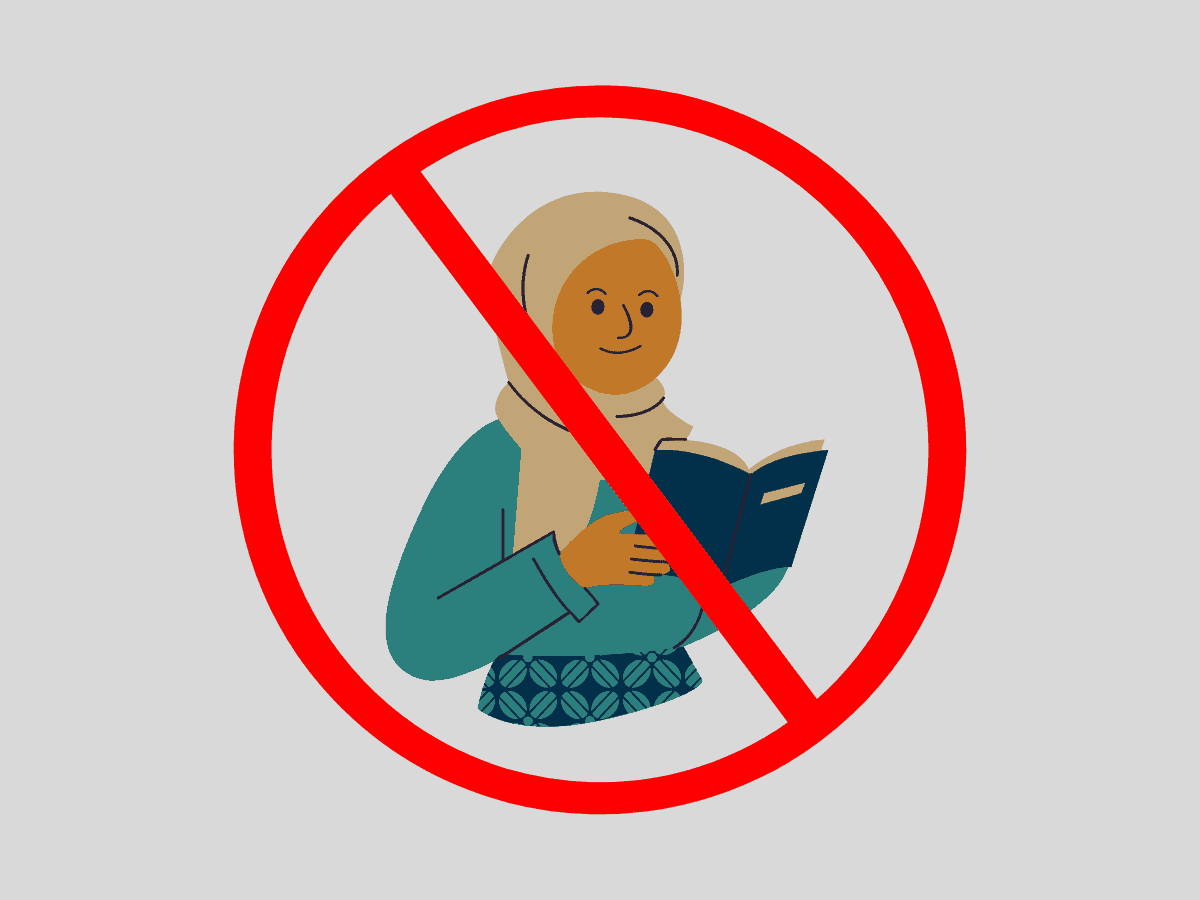

Bengaluru: The Karnataka High Court, which dismissed the batch of petitions by some Muslim girl students from Udupi seeking permission to wear Hijab inside classrooms, said there was no material placed on record to prima facie show that wearing the headscarf was an essential religious practice.

The court also said that school uniforms will cease to be a uniform if hijab is also allowed.

The following are some of the observations made by the three-judge bench of the Karnataka high court.

Lack of evidence:

“There is absolutely no material placed on record to prima facie show that wearing of Hijab is a part of an essential religious practice in Islam and that the petitioners have been wearing hijab from the beginning,” the three-judge bench headed by Chief Justice Ritu Raj Awasthi, the others being Justices Krishna S Dixit and J M Khazi, noted.

“It is not that if the alleged practice of wearing hijab is not adhered to, those not wearing hijab become the sinners, Islam loses its glory and it ceases to be a religion. Petitioners have miserably failed to meet the threshold requirement of pleadings and proof as to wearing hijab is an inviolable religious practice in Islam and much less a part of ‘essential religious practice’,” the bench observed.

Noting that the idea of schooling is incomplete without teachers, education, and a uniform, the Bench said they collectively make a singularity.

Petition lacks weightage:

Rubbishing the petition, the court remarked that the “Petitioners had also produced some ‘loose papers’ without head and tail, which purported to be of a brochure issued by the Education Department to the effect that there was no requirement of any school uniform and that the prescription of one by any institution shall be illegal.”

Underlining that no reasonable mind can imagine a school without uniform, the court observed that the concept of school uniform is not of a nascent origin.

Ancient Indian culture:

“It is not that Moghuls or Britishers brought it here for the first time. It has been there since the ancient gurukul days. Several Indian scriptures mention samavastra or shubhravesh in Samskrit, their English near equivalent being uniform,” the bench noted.

Further, the bench remarked, “in ‘qualified public places’ like schools, courts, war rooms, defence

camps, etc., the freedom of individuals as of necessity, is curtailed consistent with

their discipline & decorum and function & purpose.”

Regarding the plea that hijab of the same colour as of school uniform be allowed, the court said it was not impressed by this argument.

“Reasons are not far to seek: firstly, such a proposal if accepted, the school uniform ceases to be uniform. There shall be two categories of girl students viz., those who wear the uniform with hijab and those who do it without,” the bench said.

The two categories of girl students would establish a sense of “social-separateness”, which is not desirable, the court pointed out.

It added that the proposal if accepted will also offend the feel of uniformity which the dress-code is designed to bring about amongst all the students regardless of their religion and faiths.

Accommodating petition unreasonable:

“The statutory scheme militates against sectarianism of every kind. Therefore, the accommodation which the petitioners seek cannot be said to be reasonable. The object of prescribing uniform will be defeated if there is non-uniformity in the matter of uniforms,” the Bench said.

Noting that youth is an impressionable period when identity and opinion begin to crystallise, the Bench said young students are able to readily grasp from their immediate environment, differentiating lines of race, region, religion, language, caste, place of birth, et al.

“The aim of the regulation is to create a ‘safe space’ where such divisive lines should have no place and the ideals of egalitarianism should be readily apparent to all students alike. Adherence to dress code is a mandatory for students,” the judges said in their order.

Constitutionality- an invalid question:

Regarding the right to religion, the bench said a person who seeks refuge under the umbrella of Article 25 of the Constitution has to demonstrate not only essential religious practice but also its engagement with the constitutional values.

“If essential religious practice as a threshold requirement is not satisfied, the case does not travel to the domain of those constitutional values,” the court noted.

Quoting the Supreme Court observation in the case related to Shah Bano and others, the bench said, “We cannot resist our feel to reproduce Aiyat 242 of the Quran which says: ‘It is expected that you will use your commonsense’.”

(This story has been edited with inputs from the News desk.)