Hyderabad: At a small dwelling in Amannagar locality Shamsheera Begum, a middle-aged woman sits straightening pieces of wire that are later shaped into safety pins. For the job, she performs from dawn to dusk along with her daughter-in-law, she is paid Rs. 25 for a kilogram.

“At the end of the day we straighten 4 to 5 kgs of wire pieces,” she said.

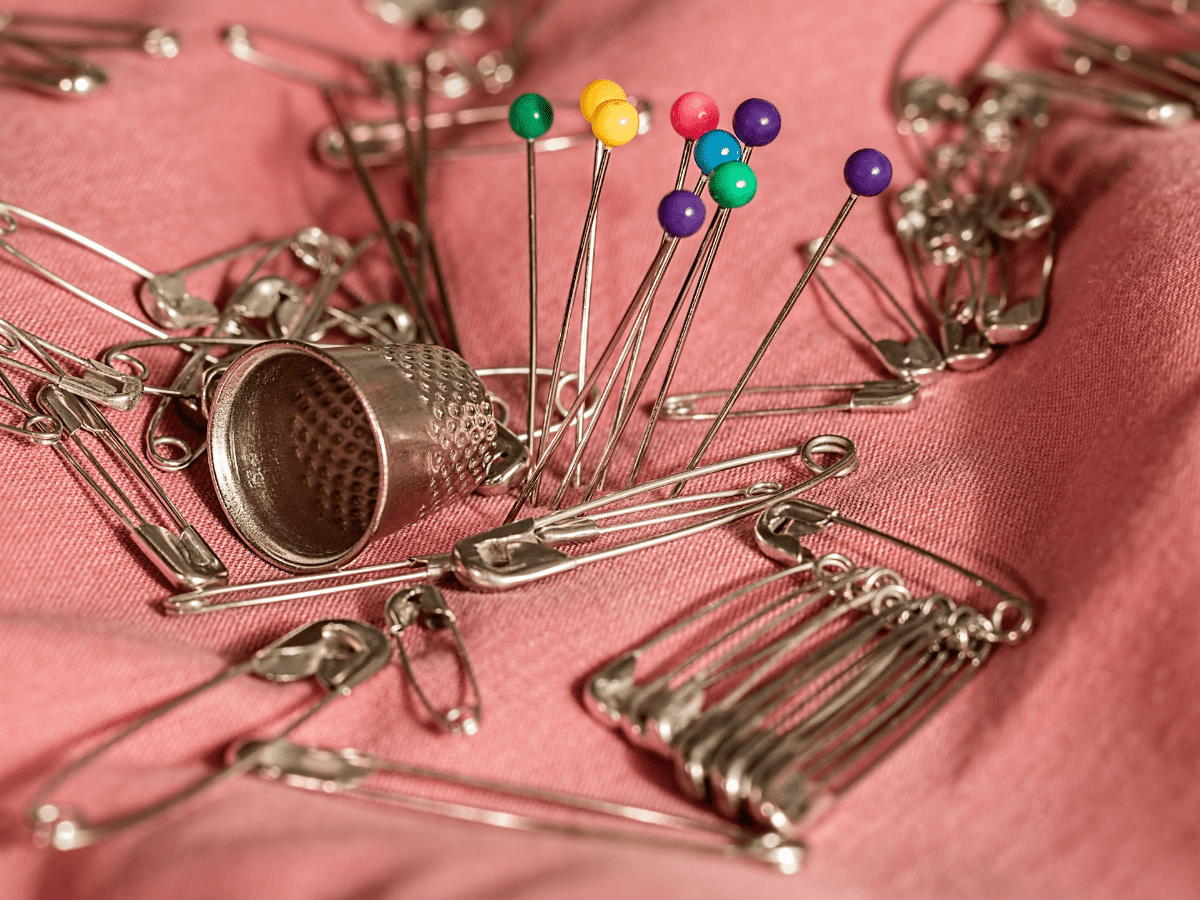

Several women in the localities of Amannagar, Siddiqnagar, Chacha Garage, Tallabkatta, Nashemannagar, and nearby areas earn a livelihood by engaging in safety pin-making vocation. Although on its last leg, the trade whatever remains feeds several families in the downtrodden areas.

“I have a family of five to look after, my husband works with a fruit trader and his earnings are meager. I do work at home. In our community we are dissuaded from going out and working so we take up small home-based jobs,” explained Farzana Begum, who still continues with the safety pin vocation.

The women send their children to the traders who supply the material to them after weighing it, after completing the task it is returned. On average a family makes around 4 to 5 kgs of safety pins.

“There are five steps in safety pin making and the process is done by different families. While a family straightens the wire, another gives it the shape of a pin, one more punches the hooks, the other polishes it, and the last family makes bundles and packs,” explained Mohammed Shukhoor, owner of a workshop. A family is paid between Rs. 15 and Rs. 25 per kg depending on the task.

The finished products were again sold through salesmen at shops in localities or markets in the city.

Amannagar, located three kilometers away from Charminar, is known for its cottage industries. Hundreds of families once earned their livelihoods in the safety pin-making business in this thickly populated slum of the old city.

However, after machines were introduced the women lost work. “Everything is coming from other States. The product is cheaper hence people prefer it due to low cost and traders selling because of huge profits for them,” said Shukhoor.

Women who were into the trade due to paucity of work shifted to other trades. “I shifted to bangle making noticing there was some demand left for this handicraft vocation, else in safety making trade we were not getting work for a week at a stretch. How can I feed my children when there is no money?” Sultana along with her teenage daughter makes lac bangles at their house in Siddiquinagar.

Around 50 workshops existed in the slum until a few years ago. Now the majority are closed and only a handful remain. “I call it the last phase of the trade,” says Shukhoor.