“It seems to me that one ought to rejoice in the fact of death–ought to decide, indeed, to earn one’s death by confronting with passion the conundrum of life. One is responsible for life: It is the small beacon in that terrifying darkness from which we come and to which we shall return.” – James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time.

Jijibisha is a Bengali word loosely translated to mean the “will to live”. Throughout his writing, Manoranjan Byapari has shown to the Indian subcontinent and the world outside of it that his words, like his own self, exhibit a strong knack, a flair for living. The flair continues reminding the reader that every once in a while the suspension of fiction is essential so that one could lend respect to reality.

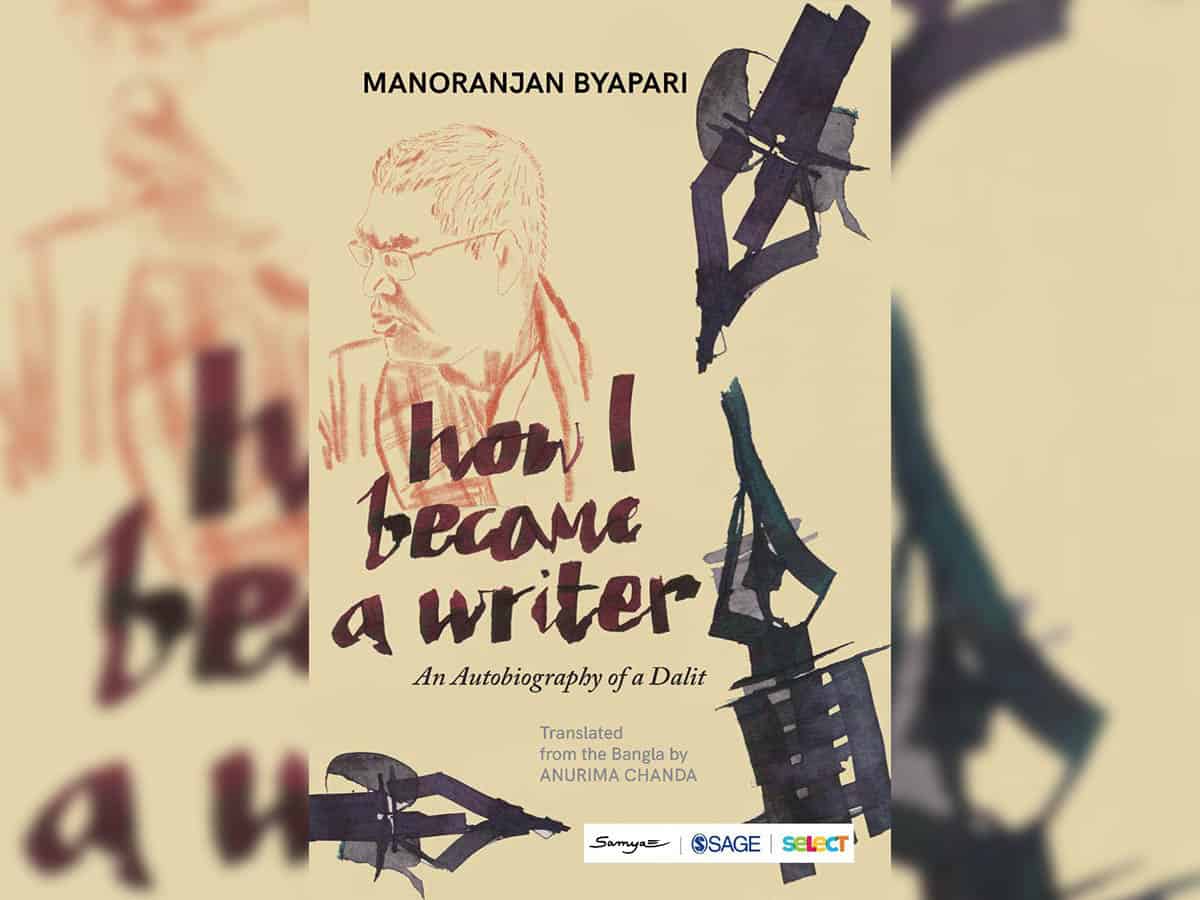

In his newly released book, How I became a writer, jointly published by SAGE Publications India and Samya under the Samya SAGE Select imprint, Byapari exhibits severe mettle, the kind which he cultivates despite a world so cruel in its employment of words. He however makes it clear that even as he finds himself sentenced to life, each word he writes, is an attempt to escape said sentence and reach for Jijibisha.

Even a quick perusal of the book’s chapters reveals how Byapari is painfully aware of memories from his early days. Working as a cook for Helen Keller’s institute for the deaf and the blind, he was subjected to visible hate; the presence of which reaffirms the fact that India’s identity is born out of caste and its perversity.

The initial chapters in How I became a writer, bares witness to the vileness of the people Byapari worked with. Titled “The Warden and the mother killer”, “The Four Guards”, “Tensions at work”, he narrates how he was hazed, bullied, made to feel humiliated for being a writer, a Dalit human, and much later on, a Dalit with the temerity to demand respect from those working around him.

Byapari narrates how he was stung by “the Mother” and the Warden’s interaction at one point. When he informed them that he belonged to the Namashudra caste (earlier referred to as the now pejorative term Chandal), the Mother stated that it was unreasonable to have hired Manoranjan as a cook, as children from Brahmin and Baniya families studied there.

She further remarked that as “Fire is a universal cleanser” she would ensure that the rice and vegetables were boiled twice a day to cleanse it off a Dalit man’s touch.

Responding to the above Byapari writes, “I didn’t like Mother’s tone. It felt obnoxious to be interrogated about caste in an organization run by Leftists. Once, I had been subjected to extreme humiliation over the caste question as a cook for a child’s rice-eating ceremony. I had never been able to forget that. Today, I was no longer so weak.”

This anecdote is just one of the many Byapari employs to discuss how little faith he has generally speaking in people around him, but on several occasions in Left politics. Even when Boro Sahib, an influential leader of the Left made Byapari feel inferior for not offering a cigarette with the respect Boro believed he was entitled to, Byapari clings to his unwavering sense of dignity.

The same unwavering sense recurs at different points; from when the children in the institute first demand and then waste the food he cooks for them, to the humiliation his wife is subjected to as she was asked to sleep in a dorm room with fifteen young men, to the time Byapari faced the wrath of an entitled journalist.

The various accounts he writes about cast a shadow on a bleak, damp world but what’s far more valuable is that from out of the darkness, they offer the solace truth, respect, and common sense seldom get credit for.

Byapari embroiders into his own humiliation and pain, the shame of the Dandakaranya and Marichijhapi massacres. He writes of violence, rape, and how hope flickered as lives went unaccounted for. His belief in God was and still is non-existent. His faith in the Left died multiple deaths as they proved to him how little they cared for peoples’ movements. And yet, he makes it clear that little matters outside of the human race to him:

If there was one thing I loved most in life, it was people. Not mountains or rivers, not fields filled with golden harvest, not the song of the birds, not the forests or its fruit-laden trees, only people and their needs. Nothing was as precious to me as people.

At another point, Byapari remarks:

..some people championing red flags had joined the refugees to play a dirty game of leading a resistance movement. People did not realize that it was merely a political move. This realization dawned years later by when they had already come into power. The hell that was subsequently opened on the poor and destitute people at Marichjhapi was capable of matching up to the Nazi atrocities on the Jews. How fascism and communism could coexist in this fashion, was not known.”

How I became a writer does not draw from imagination. It doesn’t need to any more than fantasy needs to borrow from medicine. That being said, Manoranjan’s stories do whisper hope even as they trace each account of caste and its ills. He finds hope initially in people like Charu Majumdar, Mahaswetha Devi, Meenakshi Mukherjee among others, and later on in his own successes as he stands on a stage in front of “well-bred folks” to proudly proclaim that “he writes because he cannot murder anyone.”

In a sense, James Baldwin’s spiritedness, hatred of systems and love of humanity can be found in Byapari’s Bengali ink. How I became a writer does a lot to take away from hope but while returning the same to his reader it echoes what Baldwin told Margaret Mead:

“We’ve got to be as clear-headed about human beings as possible, because we are still each other’s only hope.”