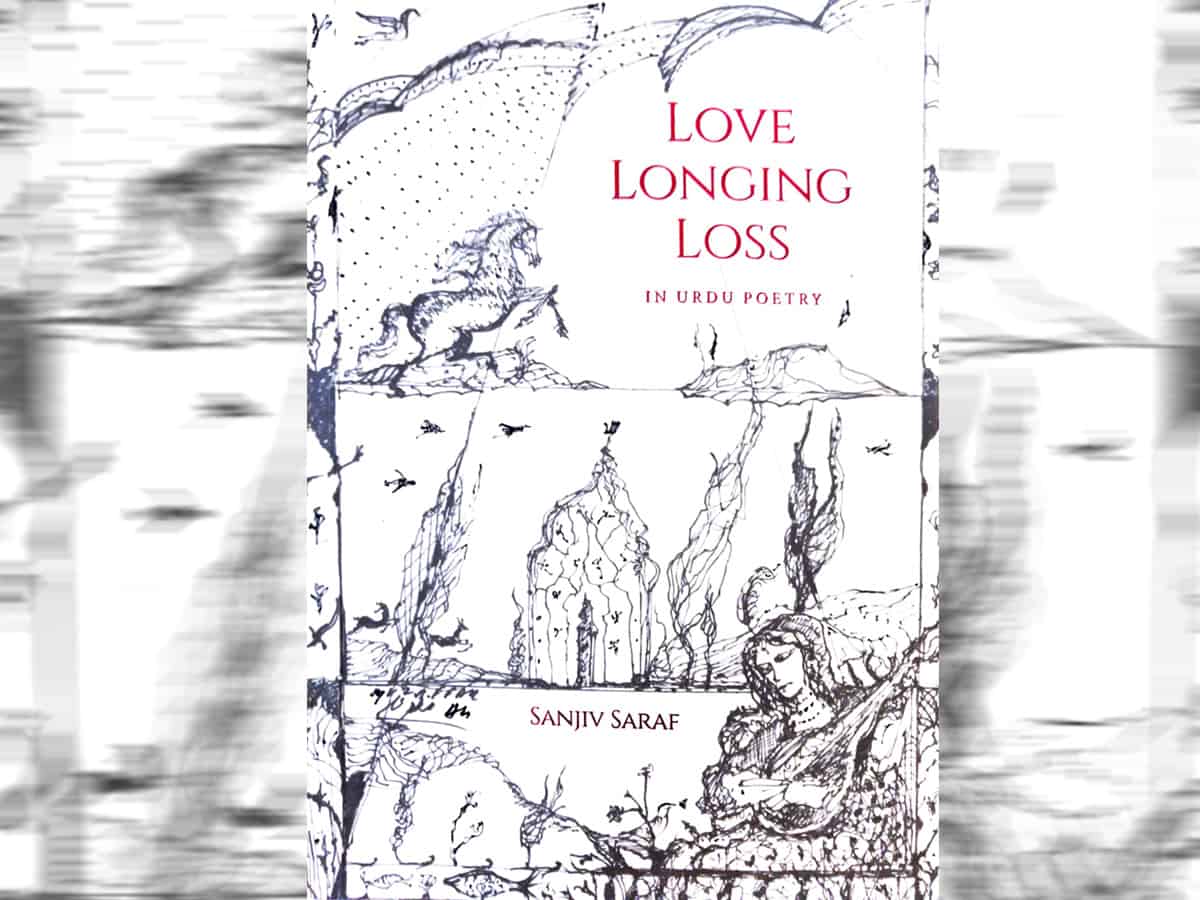

Since time gone by, humans have been enchanted by something that defies exclusivity of body and the spirit simultaneously and deflates the myth that cause-and-effect shape human thoughts and action. It strikes at the roots of determinism and servility and detects the undetected despite remaining intangible. It stands up to the dictates of the authority, both divine and worldly. Love prompts Satan of “Paradise Lost” to stand against the religious subordination by saying, “it is better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.” Much more than a romantic construct laced with sensual voracity and a means of spiritual, intellectual and emotional fulfilment, Love comes in for aesthetic contemplation for poets, and Urdu poetry is no exception. Love with all its embodied and ethereal connotations oscillating between cupidity and spiritual sublimity acutely wrapped in poignant conceits and binary tropes encapsulate Urdu poetry. How major Urdu poets radicalized or reinvented the idea of Love is skillfully told through English translations by Sanjiv Saraf, a celebrated translator and transcreator, in his latest book, Love Longing Loss in Urdu Poetry (Rekhta books, 2021).

Love is an ever-fascinating object that empowers its adherents to transcend all sorts of barriers, and one can take it for religion. It is meticulously manifested in the oeuvre of exquisite practitioners of Ghazal. Sanjiv Saraf, whose rhymed translation of Ghalib initiated a new idiom of combining translation and transcreation judiciously, now tires of unfurling various contradictory concepts of Love by going through what has been articulated by the poets. He makes prominent exponents of poetry such as Mir Taqi Mir( (1723-1810), Ibrahim Zauq (1790-1874), Mirza Ghalib (1797-1869), Momin (1800-1851), Daagh Dehlvi (1831-1905), Akbar Allahabadi (1846-1921) ), Arzoo Luckhnavi (1873-1951), Hasrat Mohani (1873-1951)), Jigar Moradabadi (1890-1960), Firaq Gorakhpuri (1897-1982), Faiz (1911-1984), Majrooh Sultanpuri (1946-2000), Nida Fazli (1938-2016) and the like the object of transcreation and translation.

Running into nearly 400 pages, the book seeks to unravel the tantalizing, titillating and poignant story of Love by producing a rhymed translation of more than a thousand couplets. At the outset, Sanjiv spells out the contours of his creative project, “having been through the entire gamut of highs and lows, infatuation and rejection, marriage and separation, attachment and alienation – I have been ground quite fine. I am somewhat attuned to the emotions and nuances of love poetry. It is the understanding which I wish to bring out in this book.”

Unerringly stringing along with his intention, Sanjiv produces a nuanced typology of Love and its innumerable connotations featuring heart, beloved, messenger, neglect, promise and wait, lovesickness, possessiveness, rivalry, infidelity, frenzy, tyranny, alienation, separation, death wish and the like. He impeccably showcases how Urdu poets portray the Love that simultaneously conjures up the most intimate and unlikely feelings. Love is a slippery word that defies categorization, and it cannot be understood with any external reference. Much talked about, but the undefined concept of Love still prompts poets to answer the perennial question, “What is Love? Here Sanjiv ropes in Mir, Ghalib, Jigar and others. For Mir, it is self-contained: “Ishq mashooq, Ishq ashiq hai/ “Yaani Apna hii mubtala mubtla hai Ishq. (Love is the beloved, Love’s the paramour / Love is thus enmeshed / in its own allure).

Ghalib, one of the most influential voices of the Indian mind, creatively delineated subtle nuances of Love. He describes it as an all-consuming passion: “Puchhe hai kyaa vajud-o- adam ahl-e-shauq ka/ aap apni aag ke khas-o-khashak hog gaye.” Of lovers being and nothingness, what do you not enquire? / Brushwood, kindling they’ve become, for their own desire).

It is not a run-of-the-mill anthology carrying free verse translations of Urdu poets as Sanjiv refers to many English and Indian poets while attempting rhymed translations. Love goes beyond loss and gain. Before translating Siraj Aurangabadi (1715-1763), he quotes John Dryden (1631-1700), who said, ‘Love is Love’s reward. Siraj articulates, “Aaiyi hai tere ishq ki bazi dil-o-jan par/ Is waqat nazar ka bhai mujhe suud-o-ziyan par” (I wager heart and life/ on my Love for you / At this time, profit loss, I keep not in view.) Sanjiv mentions Oscar Wilde’s (1854-1900) assertion, “Who, being loved, is poor?” and then he brings up Salim Ahmad(1927-1983): “Jo suud-o-ziyan kii fiker Kare/ yoh Ishq nahi mazdoori hai (Of profits, loss in which you fret/ Is not love but toil and sweat).

Trials and tribulations, mirth, self-absorption and disappointments of Love are told through various symbols and images. For the author, temple/mosque/prisoner/ captor/rose/bulbul and flame/moth are major tropes. Where does Love germinate? Obviously, it is the heart which is also referred to as jigar (liver) by Urdu poets, and it is a soundless tumult as Iqbal (1877-1938) says: aah duniya dil samjhati hai jise vo dil nahi / pahlu-e-insan mein ik hangama -e-khamosh hai” (that which the world believes to be/a heart, alas is not/It’s a silent storm that, in /a person’s breast is wrought’).

The rhymed translation of Urdu poetry that revels in a rhetorical flourish and emotive language is a herculean task. Sanjiv does it with remarkable ease though turgidity occasionally surfaces. One tends to go along with the eminent critic and scholar Professor Gopi Chand Narang, who opines, ‘the book is destined to initiate a new discourse on the poignant portrayal of Love as an ever-alluring object.