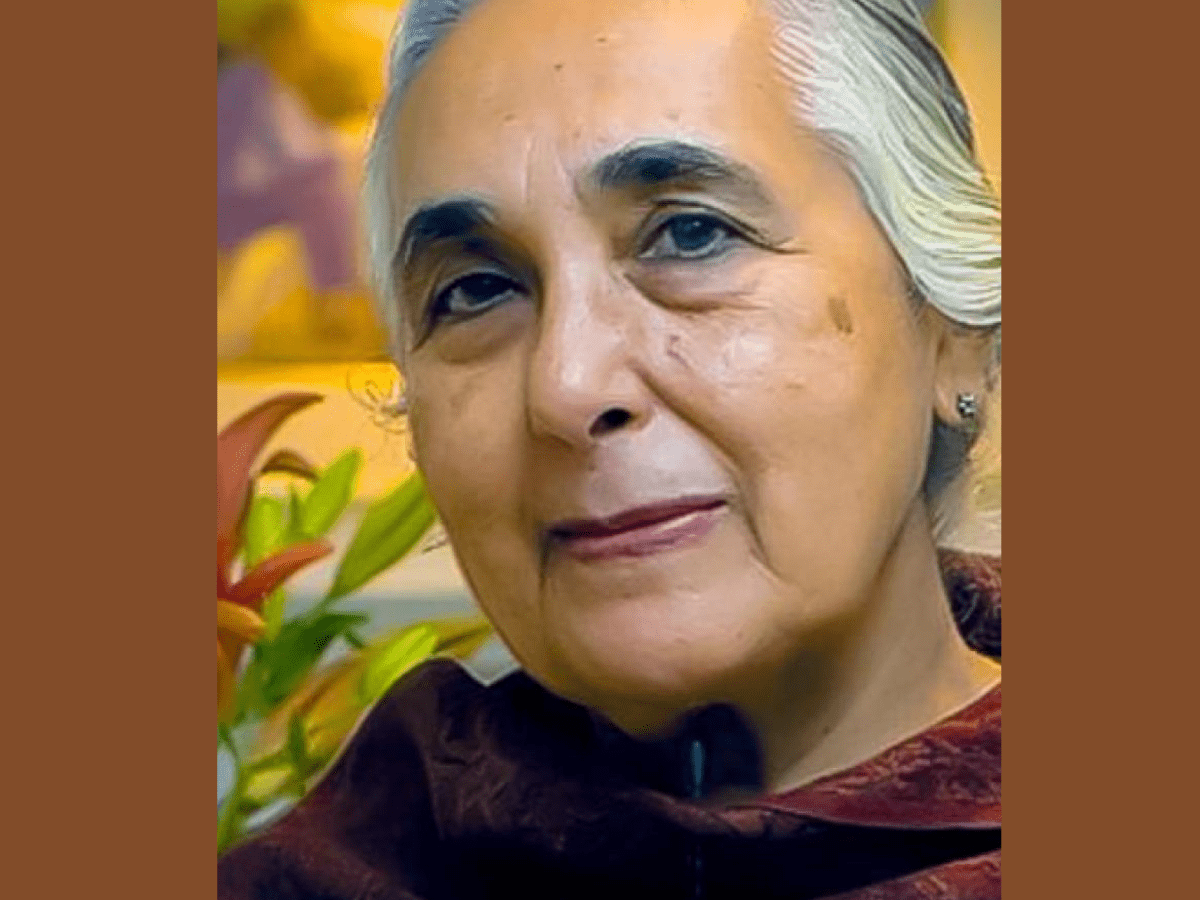

New Delhi: Historian Romila Thapar has stressed the need for a professional and evidence-based approach to history instead of one by untrained historians about victimization based on religion.

Delivering an annual lecture at the India International Centre on Saturday on the topic “Our History, Your History, Whose History?”, she focused on the relationship of history with nationalism and cited various historical evidence to negate the victimization theory.

She contended that there was no “love jihad” in the earlier days and that besides politics, marriage alliances were intended to strengthen social bonding.

“Love jihad” is a term often used by right-wing activists to allege a ploy by Muslim men to lure Hindu women into religious conversion through marriage.

Thapar began her lecture by quoting eminent British historian Eric Hobsbawm that history is to nationalism what poppy is to a heroin addict. “What comes from the poppy and enters the mind of a heroin addict conjures fantasies about a magnificent past or otherwise about which fantasy sustains the present,” she said.

According to her, nationalism aims for building a nation in line with the one dreamt of during the struggle for Independence where citizens are free of colonialism.

Contrary to this unitary form of nationalism which was evident during the national movement, divergent or segregated forms of nationalism identified by religion grew out of colonial rule, Thapar said.

She contended that the purpose of segregated nationalism is to give primary status to the group that counts the majority and it is legitimised by claiming links to ancient history. This causes confrontation between professional historians and untrained ones, she said.

British historian James Mill, who in 1817 wrote the first modern history of this country — The History of British India — maintained that Indian history was that of two nations, the Hindu and the Muslim, quite distinctly separate and constantly in conflict, she said,

“Indian history was periodised into the earliest Hindu period when Hinduism was powerful followed by the domination of Islamic rulers. This periodisation, which has been discarded now by professional historians, deeply coloured the interpretation of Indian history,” Thapar asserted.

“Secular and democratic nationalism focussed on the singular movement for Independence while the two religious nationalisms Muslim and Hindu divided the nation between them. The Muslims culminated in Pakistan and the Hindus are edging towards a Hindu Rashtra. The colonial projection is succeeding,” she claimed.

She said that the historical sources researched by professional historians read differently and do not rejuvenate the view of colonial historians.

“The Mughal economy was in the trusted hands of the Wazir Raja Todar Mal, while Raja Man Singh of Amber, a Rajput, commanded the Mughal army at the battle of Haldighati. He defeated another Rajput — Maharana Pratap — who was an opponent of the Mughals. Pratap’s army with its large contingent of Afghan mercenaries has as commander Hakim Khan Suri, a descendent of Sher Shah Suri,” Thapar said.

“One could ask whether the battle was strictly speaking essentially a Hindu-Muslim confrontation. Both religious identities had participants on each side in a complex political conflict,” she added.

Going beyond the complexities of politics, she highlighted marriage alliances that were intended to strengthen social bonding.

“The Mughal royal family married into Rajput royal families of high status. Since Muslims as non-caste aliens were treated as ‘mleccha’ by upper caste Hindus, did the Rajput ruling families lose face marrying into a ‘mleccha’ family even if it was the imperial family?” she posed.

“Apparently not. Was it a matter of pride that they were marrying ‘up’ as it were? There was of course no ‘love jihad’ in those days. Memoirs and autobiographies do not suggest that these were forced marriages since sociability among them on both sides was applauded,” Thapar added.

Holding that fake news is creating immense problems, she made a plea that the history taught in schools should be based on reliable evidence and preferably be the history of professional historians.

She went back to the metaphor of Eric Hobsbawm and questioned, “Should we let the relationship between the poppy and the heroin addict remain as it is? Or should we insist that the heroin addict should question the visions seen? Or, should we reassess the quality of the opium? All knowledge advances by asking questions.”

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by Siasat staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)