Domesticity, often criticised, is a powerful expression of women’s complex intellectual and profoundly emotional existence. It is more than just a sentimental utterance. Despite the feminist suspicion of marriage, family, and housekeeping as defining elements of women’s identity, domesticity can evoke images that express a rich and varied range of human sensibilities. The creative skill of a poet can redeem and revise the idea of domesticity, using its imagery to deconstruct and reimagine it. Hyderabad-born Pakistani octogenarian poet Zehra Nigah, with her poetry that is nothing short of transformative, enlightens and inspires us by tearing apart the much revered but essentially constrictive feminine ideal- motherhood and, with the sledgehammer irony, she shows how ovation reveals disrespect:

My children say:

“When you come, brightness and fragrance come to our house.

This haven that we have found is because of these feet.

To have you stay with us is our great good fortune”.

With much difficulty, I wrenched myself free and returned. /I remember those tears and those sorrowful faces: “Do not go just yet. Stay”. How those pleas torment me! I tell this entire tale to all those who come to meet me. /Everyone recognises the falsehood entwined in my speech / But they are decent people; they agree with everything I say. (The Tale of a Truthful Mother, translated by Rakhshanda Jaleel)

Here, motherhood goes beyond a mushy social construct. Mothers are adored but hardly get what they rightfully deserve.

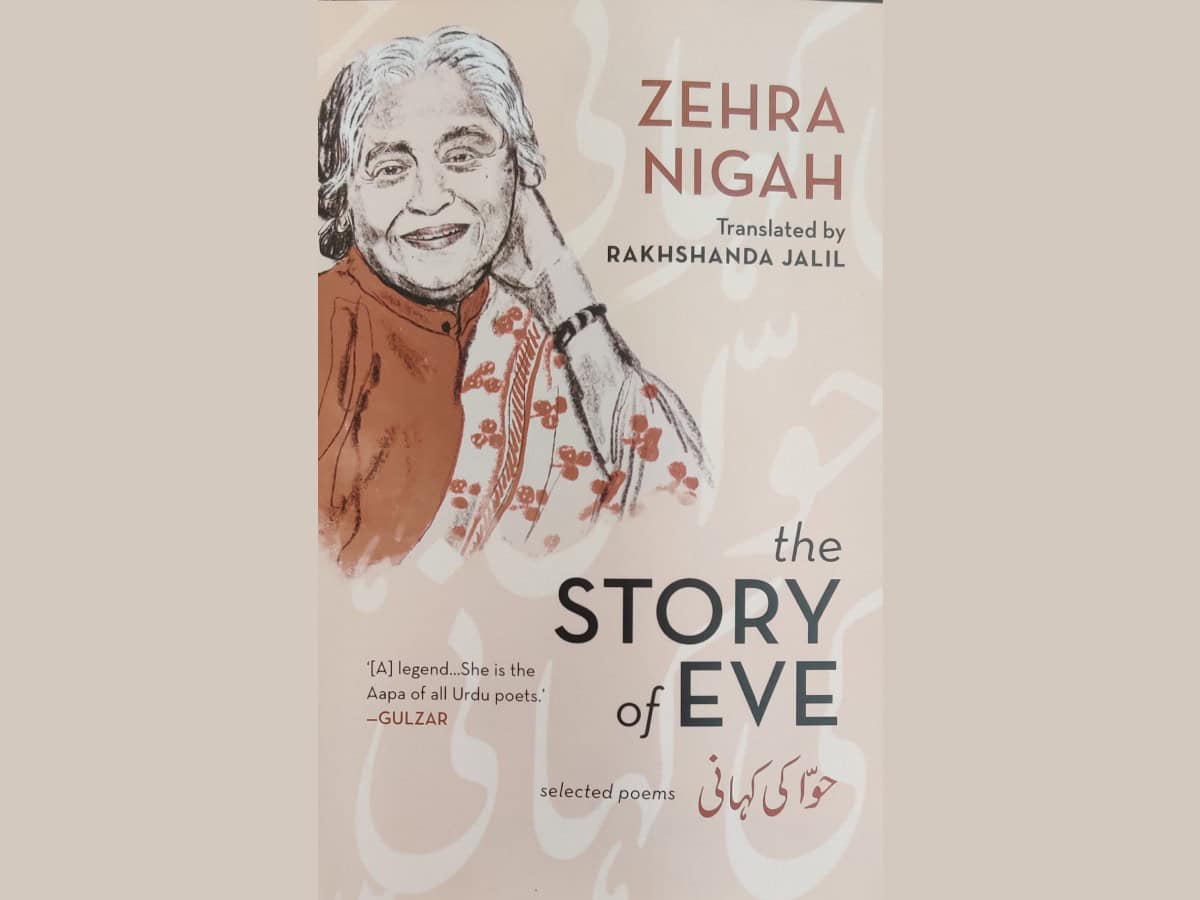

It is a seething comment on much-revered motherhood by Zehra, the first to carve out a niche in the male-centric world of Urdu poetry. Her evocative poetry, wrapped in a conversational idiom that creates waves in the subcontinent, has now been made accessible to non-Urdu speakers by Rakhshanda Jaleel, a celebrated translator and distinguished literary historian. Rakhshanda’s succinctly eclectic selection from her four selections Shaam Ka Pehla Tara (The First Star of the Evening), Warq (Page), Firaq (Separation), and Gul Chandni (Flower of Moonlight), The Story of Eve (Speaking Tiger, 2024) carries all her widely admired poems and ghazals. The anthology provides intimate access to

the oeuvre of Zehra, who refuses to be known as a “women poet.”

Zehra writes ghazals and nazms with equal felicity and tells more than the tantalizing tale of unrequited love and alienation. She is the first to carve a niche in the male-centric world of Urdu poetry, a feat that deserves our utmost appreciation and respect. Her evocative poetry, wrapped in a conversational idiom that creates waves in the subcontinent, has now been accessible to non-Urdu speakers. Zehra appropriated traditional feminine imagery in her stellar poem, the Story of Eve, without evoking the sentimentalized image of women to undermine the myth concerning the first woman. This use of conventional imagery is not a rehash of history but a powerful tool to critique and redefine womanhood, showing that unflinching loyalty, not a beguiling attitude, sums up womanhood.

I did not compel you to eat the apple

Nor was that grain of wheat grown on my palm,

And the serpent -he was no friend of mine.

If I had a friend, it was you. If I loved someone, it was you. (The Story of Eve)

The incongruity between the mystique and reality often disconnects one from all emotions, producing a sense of compromise that sustains one. It transcends joy and sadness. Compromise is a construct, and so are truth and lie. It does comfort but also creates the haunting air that propels life:

Warm and soft, the blanket of compromise

it has taken me years to weave.

Not a stitch of falsehood betrays it.

It will do to cover my body,

and it will keep you satisfied, although

it will bring you neither joy nor sadness.

Stretched, the screen will fall overhead; it will make us a home.

Spread beneath us, it will brighten up our courtyard

when we drop it, the screen will fall (Compromise)

Here, compromise in the conversational idiom is not treated as a look of sentimental drivel but as a complex apparatus in sync with the lasting bond that

the feminine mystique promises. These poems prompt one to agree with Rakhshanda, who astutely spells out Zehra’s aesthetic and thematic concerns: “Treading a fine line between feminism and feminine verse, she has steadfastly refused to allow gender to dictate her choice of subjects. Her poetry is as much about the compulsions and compromises of being a woman and a poet as it is about a sensitive, thinking person’s response to all that is happening in the world around her. To her, “the sorrow of the world is as important, if not more, as the “sorrow of the heart’.”

Unlike some of her voluble contemporaries, Zehra Nigah does not affirm that the victimisation of females is the sustenance of men who also live off the labour of their partners. Unequitable domestic labours of life hardly leave him exasperated as indulgence in those sorts of works provides her with an opportunity for self-expression. It is contrary to what Adrienne Rich (1929-2012) observes:

Two people in the room, speaking harshly,

one gets up, goes out to walk (That is the man)

the other goes into the next room

and washes dishes, cracking one (That is the woman).

The selection comprises 65 poems does includes all well-admired renderings of Zehra such as, “Send Mercies upon us, O Prophet Ji”, I was saved, Mother, I was saved, “The Tale of Gul Badshah,” Scheherazade In London, the commodity of words, Sylvia Plath, Exhaustion, Old, Rakhshanda, who translates from Urdu to English and vice versa with remarkable ease, rendered eleven representative ghazals of Zehra into English. Notwithstanding occasional portliness, it is an engaging rendering of the poetry that asserts women are more than domestic functionaries without strident polemics.