“Our lives, our stories, flowed into one another’s, were no longer our own, individual, discrete.”

― Salman Rushdie, Shalimar the Clown

“Anything worth doing transcends borders.”

― Geetanjali Shree, Tomb of Sand

The proof of democracy, of citizenship is not found in the voting process (which crops up once in five years) but in the possession of papers. Individuals, to be considered part of a republic, need paper-proof; no matter how crumpled or faded or browning.

The glaring necessity for papers was felt with the introduction of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) in 2019. What the CAA-NRC protests showcased was that there exists in India a certain documentation anxiety.

“Was their baap-dada (father-grandfather)’s kaagaz (papers) really necessary? Did their entire lives and those of their children not qualify as evidence?” These were some of the questions the protestors were forced to confront with at the peak of the agitation.

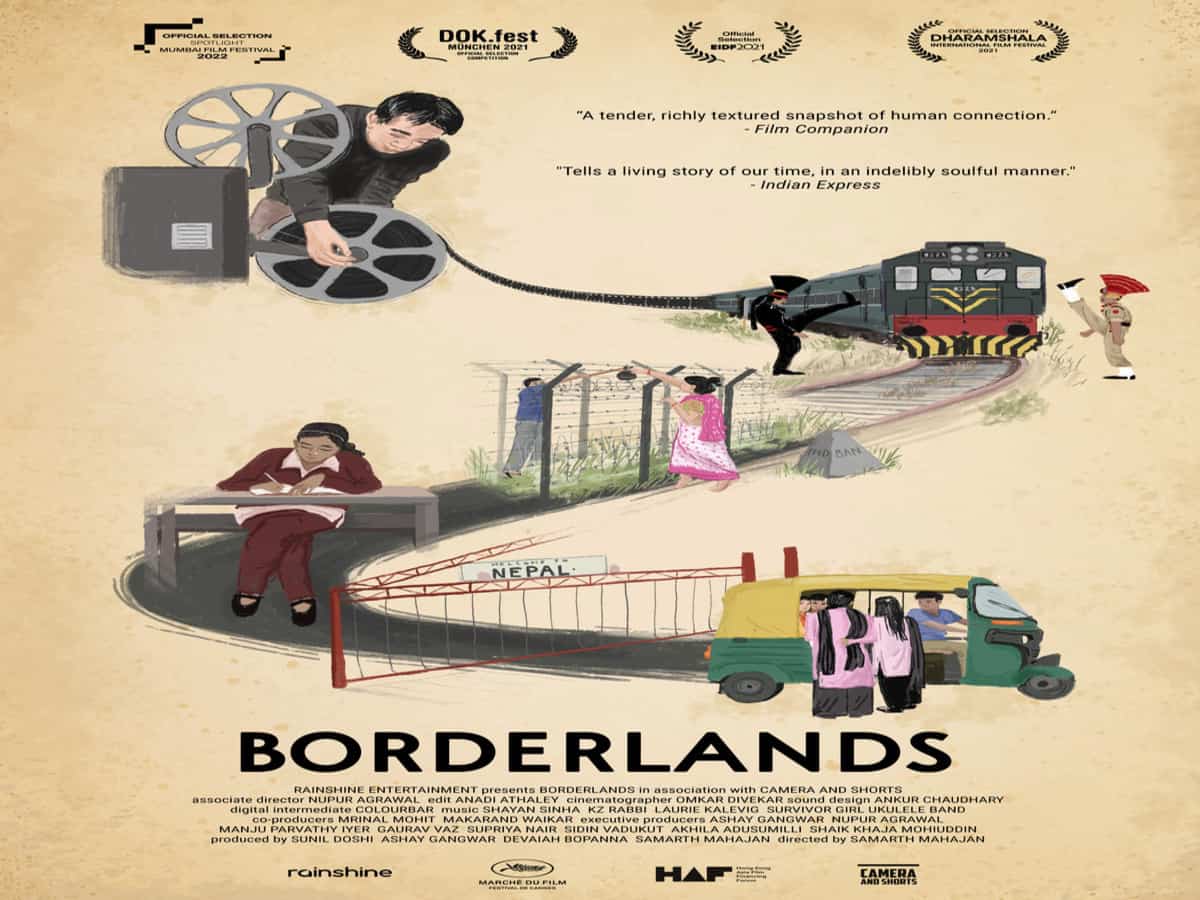

This bureaucratic sentiment of “If the papers don’t exist, neither do you” however weakens a little while one views Mumbai based documentary filmmaker Samarth Mahajan’s work Borderlands. Chronicling the lives of six individuals (five of whom are women) on the borders of India, Mahajan without intending to, proves that when documentation in a political sense retains an unpleasant complexity, documentation of a different kind hits back.

“I started shooting for the documentary in 2018, way before CAA was introduced. But the introduction of the Bill in the Parliament increased the urgency of putting these stories out there,” remarks Mahajan while speaking to me.

Flexible lives, stagnant borders

Mahajan’s six protagonists, five of whom are women, all have struggles born out of and despite the borders. Deepa, a Pakistani Hindu girl who moved to Jodhpur, Rajasthan giggles as she states that she dressed however she wanted in Pakistan and threatened to take her life if asked to dress differently. As her adolescent joviality hooks the viewer, Deepa also evokes a quiet sympathy when she smiles, pauses, and then lets her lower lip quiver at the thought of her future.

Deepa’s aspirations to study medicine are somewhat delayed and potentially in peril if one were to consider how movement often stalls a person’s prospects. One cannot help but pause and lament briefly, as she tells the camera, “I will be pretty when I am happy again. I am not happy right now.”

Dhauli, who left her familial home in Bangladesh desperately waits for Milan Bazaar (a meeting of individuals from across the border) to meet her brothers. She tells the camera that she was concerned about the fence, set up between the two countries as that meant she wouldn’t be able to see her family again.

“I thought I would die of suffocation,” says Dhauli even as she informs that she rebelled against her family to come to India.

The idea of home and borders are too deeply enmeshed to pursue separation. The documentary, in all its Malgudi Days-esque music and RK Laxman-ist scenery still stings and leaves the viewer morally confused even as young girls in a rescue home play the Ukelele and older women at the India-Bangladesh border unfold Dhaka cotton sarees.

The ambiguity posed by borders

“It wasn’t deliberate at the get-go. But in retrospect I suppose, we were keen on breaking down the hyper-masculine identity associated with borders,” remarks Mahajan.

As the film rolls on, one wonders if the idea of home has to be so tiresome, if nation-states are at all helpful and if borders are just dreadful lines we are better off without. The documentary of course doesn’t answer any of these questions. Neither does it explain why our democracy is stranded. It assumes, rightfully so, that it is.

But questions of morality, choice and such (which the viewer has to sit and answer for herself) are brought up as Borderlands traces the lives of Rekha (a deeply pariotic Indian who still feels josh at the thought of serving her motherland), Noor (a queer Bangladeshi girl, who was trafficked into India and has been living in a shelter-home since), Kavita (a young girl rescuing other women from human trafficking) and Surjakanta (a filmmaker, who hopes to shed light on Manipur’s secessionist concerns with the Indian union).

The work in simple (and on its own) terms makes the case that the centre of India has held because the corners, time and again, crumble. It is in exploring this that Mahajan succeeds. While speaking to me he remarked that “Every Indian’s life is influenced by the borders,” and as such the words uttered by folks on the quite-literal margins matter.

Documentation culture will never die. Our bureaucracy won’t let it. But luckily for us, neither will any other form of documentation as long as creatives look beyond papers.

(Borderlands will be screened at Lamakaan, Hyderabad on September 3rd at 6:30 pm. The screening will be followed by a virtual discussion with director Samarth Mahajan and associate director Nupur Agarwal.)