“By the time she had grown sharper,…, she found in her mind a collection of images and echoes to which meanings were attachable- images and echoes kept for her in the childish dusk, the dim closet, the high drawers, like games she wasn’t big enough to play.”

Henry James’s 1850s novel What Maisie Knew clawed into and dug out the idea that children are in possession of awareness; be it about the world around them or their own selves. This idea, often finds itself on shaky grounds if one were to consider and buy into how celebrated the idea of innocence is.

To ascribe innocence chiefly to children is to devalue and abuse the fact that children often bear witness to a harshness in the world which stays etched in their memory. Memoir, born out of the late 15th century term mémoire (to mean memory as we understand it today), has time and again in various laps of history, proved the need for one to value memory. It is only by valuing and chronicling memory one could explain cruelty, injustice in a world prone more to legislations than stories.

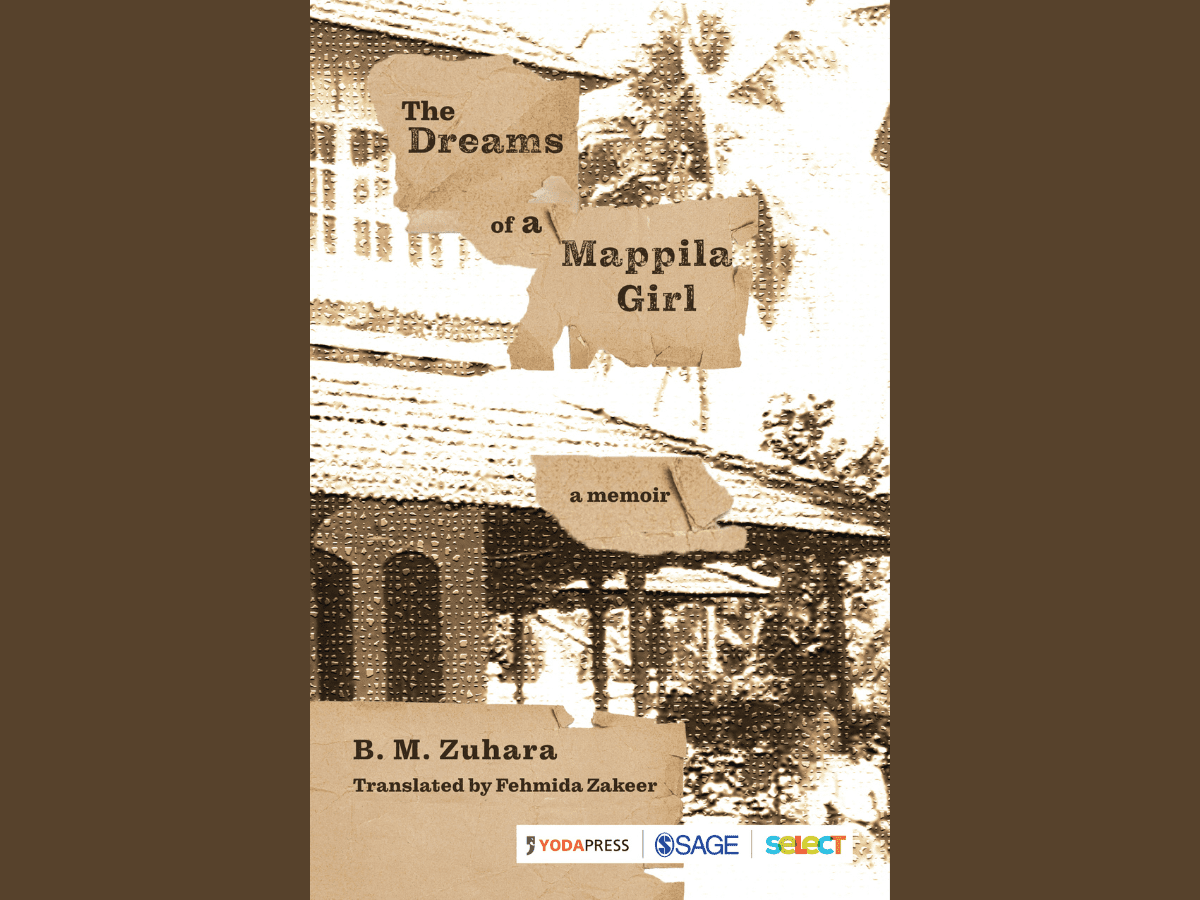

BM Zuhara’s account of her childhood in her memoir The Dreams of a Mapilla Girl, translated by Fehmida Zakeer and jointly published by SAGE publications and Yoda Press under the Yoda-SAGE Select imprint takes jabs at aristocracy even as she demands that we understand the class. Narrated by Soora (Zuhara), an ever-anxious “cry-baby” heading towards puberty, the memoir expands on the lives of women living in an aristocratic Mapilla family in the Malabar region of Kerala.

The first thing that struck this reader was the dearth of any private realm despite the size of the house they resided in. The women lead a life with a solemn belief in family and community to the point where their only refuge was reading the Hadith or the Quran. Religion, while hindering their movement towards modernism, also was their only realm of privacy.

However, through the story, Soora’s relationship with religion is an inheritance passed down from her mother, Umma onto her and her brothers. Soora while accepting it, also finds herself questioning it on a couple of occasions much to the chagrin of her mother. Unlike her mother who needed the religion to explain the world, Soora found herself inching towards instinct; the kind which asked why her brothers could do things she couldn’t, why she can’t be a lawyer and why her complexion was derided.

Soora keeps winning the Bechdel test with a simplicity unique to young females. While her mother, her aunt and the helps employed in the house make it clear that their thoughts are not independent of men, Soora finds herself drawn to grit found in members of her own sex.

At a certain point in the memoir, Soora befriends Ammalu (a classmate hailing from a poor family). The two girls talk about how the lack of money poses a problem, how hygiene is fact of privilege. When asked at home why Soora continued to spend time with Ammalu despite the lice in her hair, Soora remarks that there isn’t enough money or time for Ammalu to spend on washing her hair.

Soora’s loneliness and grief lend to her keen sense of curiosity and justice despite the confines she is asked to abide by. She finds herself fuming at her brother who keeps pulling her leg, and is annoyed by the power elders wielded over children. Ever her tears, what she is chided for the most, are a result of a realisation that this world of hers, while a home in every other sense, also carries the markings of benign injustice.

The family in The Dreams of a Mapilla Girl, is characteristic in every way except its unhappiness. Born to wealth, they find themselves losing it bit by bit only to be sidelined by “classier” cousins towards the end. A relative of Soora’s, finds himself struggling with hysteria as another brother of hers wonders how “an apparently normal person could suddenly turn into someone who has to be locked in a room.” The small snippet reminds one of Bertha Mason from Jane Eyer with the chief difference being that while Soora was fearful of her unwell relative, she finds herself sympathetic to his condition.

The memoir chiefly begs the question of what makes up a home. Is home still home if its inhabitants find themselves less well off than before? Is it still home if you disagree on how our privileges are worthy of derision? Or more importantly, is it still home if you find yourself upset and vexed by everything your family stands for?

BM Zuhara seems to initially make the argument that home is where her mother is or more specifically where loneliness is a distant visitor even if grief isn’t. As she notes in her preface, her mother’s death created a vacuum in her life. “Loneliness engulfed me,” she writes.

What however stands out by the end of The Dreams of a Mapilla Girl is that for Soora, home is a place where her memories reside. And as she starts to move away from her home (geographically speaking), it still remains an “incandescent coral nestling” in her dreams.