Waqf properties are allegedly sought to be the subject of ill-informed comments masquerading as “analyses” to wrongly suggest that Muslims in India take over lands and properties without legal rights. There are no restrictions or prohibitions that control the properties. They are anathema in a secular country where adherents to one religion ought not to be given preferential treatment over adherents of any other religion, or of society in general. We hear a movie projecting these matters in a factually distorted manner projects an incorrect, if not false image, is also to be released.

It becomes necessary for us to have a correct idea and an understanding of what waqf is, what the regulatory mechanism in respect of waqfs is, and also see whether it is factually correct that allegedly preferential treatment is noticeable by either the executive or the judiciary insofar as waqfs are concerned.

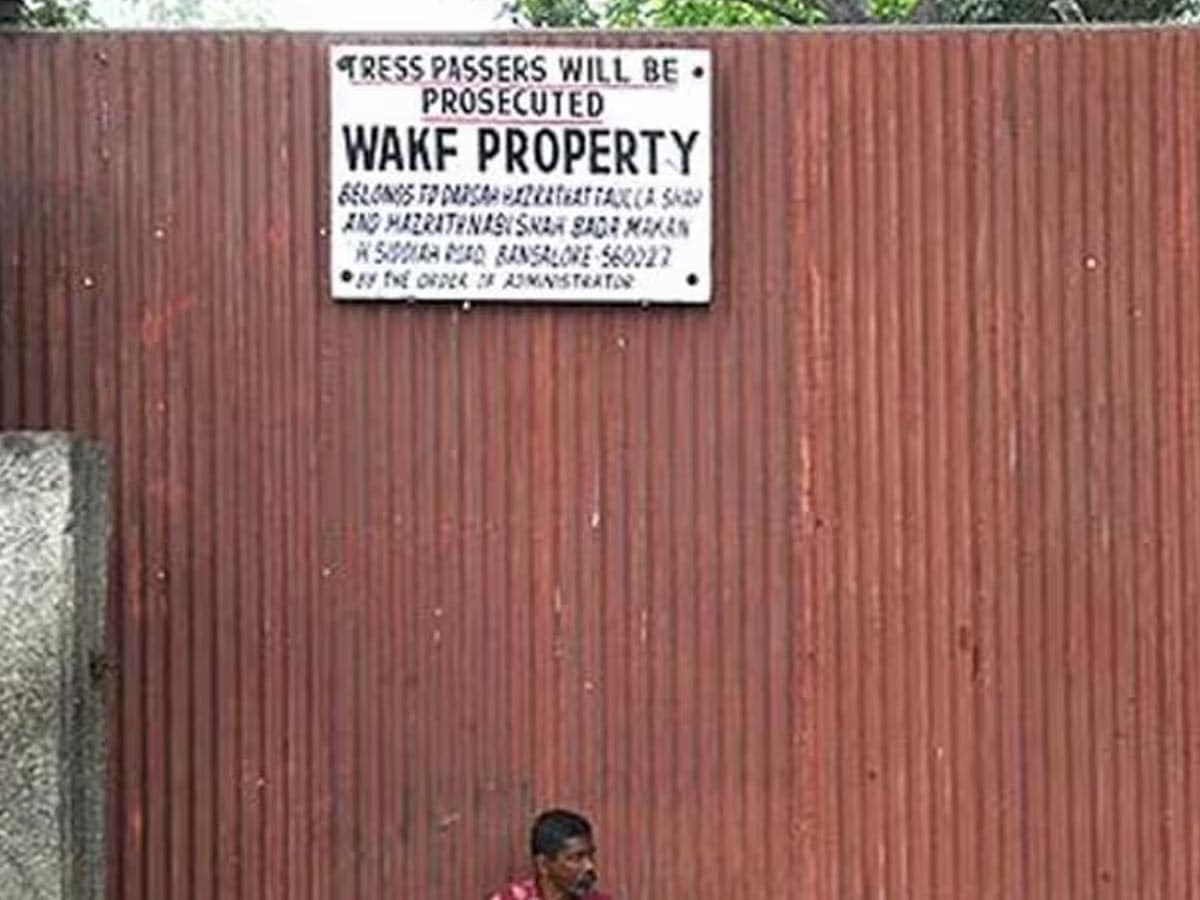

According to officials, there are 8,70,000 Waqf properties in India, on an area of 9.4 lakh acres. How could this be? How did the waqfs acquire such huge holdings? By definition, all mosques, dedicated graveyards, grants for service to a waqf institution, or any purpose recognised by the Muslim law as pious, religious, or charitable, are waqfs, and these can be by documented dedication (waqf-nama) or identified for such purpose (muntaqab) and can be waqf by immemorial usage.

It is common knowledge that today religious affiliations are weakening and the so-called liberal, drifting, fluid mind-set has taken people away from spirituality towards materialism. This was not the case and has come about only during the last few centuries. When Kings ruled the land and had higher spiritual inclinations, as owners of the entire State that they ruled over there were many instances of large extents of thousands of acres of land including entire villages being dedicated by them, for purposes considered religious pious or charitable. Lands were not as expensive as they are now. It is not unknown for Muslim rulers to have granted lands for temples or Hindu rulers to have made grants in favour of Muslim institutions, especially waqfs or mosques. These grants, by Muslim rulers or Hindu maharajas, intended that those lands so granted would be used for ensuring the availability of funds for the continuance of religious observances in those places, Hindu or Muslim. Those were days of harmony (ek voh bhi thhaa zamaana) and continued undisturbed for centuries, unlike today’s (ek yeh bhi hai zamaana) exclusion mind-set which is politically fashionable as well as a source of advantage and alleged immunity for some, from rigors of the law.

Does the State favour Muslims in respect of waqf properties? If so, would the State not have allowed 1654 acres of Manikonda Jagir of Dargah Hussain Shah Wali to be declared waqf? Do the courts favour Muslims in respect of waqf properties? Check the same case of 1654 acres of Manikonda Jagir of Dargah Hussain Shah Wali held not waqf property. Other cases need not be mentioned. Why create acrimony, and vitiate an already charged atmosphere? Are the Muslims making unjustified claims to exert illegal dominion over property belonging to the public or government or other private persons or are the facts otherwise? Note more and more instances of non-Muslims questioning waqfs are seen, sudden demolitions of properties by State agencies noted, not an increasing number of claims of properties being waqf. Is there any evidence of an increase in the officially stated figures of 8,70,000 Waqf properties in India, on an area of 9.4 lakh acres? If not, which hypothesis does this allegation emerge from?

One write-up asserts “Recently, the Supreme Court of India denied permission for the Ganesh Chaturthi celebrations at the Eidgah Maidan in Bengaluru after the Karnataka Waqf Board raised objections against such celebrations at the said location claiming ownership of the land. This has again brought into focus the prevalent practice of Waqf in an “allegedly secular country” and the functioning of the boards maintaining them.” Waqf counsel argued the waqf documents date as far back as 1931 and in 1871 where the Eidgah is mentioned. The write-up does not say why it was considered necessary to hold those celebrations there when there was no particular reason for selecting that spot. In the context of strident claims in respect of other sites, a climate of hostility towards sections of the population and their religious assets, can it be argued that the intent could be to create a precedent, then follow it up with annual events, then enhance the claim to something more? Has it so happened that in certain places, places of worship of some sections have come under “competing claims”? Once an event is allowed, once a structure is allowed to be built, do we see the political will to reverse such things? If not, given “judicial restraint” and administrative looking away in some places, and palpable administrative enthusiasm in others, ought a situation to be allowed that is fraught with potential for later conflict or confrontationist situations to aggravate? “Allegedly secular country,” it says. Supposing we agree, for diametrically opposite reasons?

What is a waqf? Waqf is the dedication of property or assets including usufruct from property, or cash, etc., for purposes that are considered religious, pious, or charitable under Islamic law. The property or asset then becomes the property of Allah. Since once property is given away the gift cannot be revoked except with the consent of the donee, the reversal of such dedication is considered impermissible and that is the basis for the statement “Once a waqf, always a waqf”. If the property is dedicated for a specific purpose that property cannot be used for any other purpose: an aspect that was lost sight of when one judgment erroneously suggested that the salaries of Imams of mosques should be paid by the Waqf Boards. Such Boards are entities of which the constituents are persons elected from among the mutawallis or trustees of the various waqfs in the State and therefore being merely a representative body of the various mutawallis or trustees, these Boards have no power whatsoever save to ensure that each waqf operates within the objectives of that waqf (the mansha’-e-waqf) and for funding the supervisory role of these Boards each waqf is required to pay to the board 7% of its annual income.

Shafeeq Rahman Mahajir is a well-known lawyer based in Hyderabad. He writes on a variety of legal and constitutional issues.