Hyderabad: After years of struggle, Telangana was bifurcated from Andhra Pradesh and it finally came into existence as a new state of the Indian union on June 2, 2014. Today, in popular memory, we mostly remember the 2009 protests, led by chief minister K. Chandrashekhar Rao (KCR) and Prof. Kodandaram, and the year-long 1969 statehood movement.

However, Telangana was originally meant to be an independent state, and decades of struggle could have been perhaps avoided had the then Indian government had some foresight.

The States Reorganisation Commission, formed by the Indian government headed by Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, in 1955 also recommended against the merger of the Telangana and Andhra regions as a unified Telugu state based on linguistic commonality. But the merger still happened and became a reality on November 1, 1956.

A historical glance of Telangana’s socio-economic background will provide for a better understanding.

Telangana region’s background

All of the Telugu speaking regions of Telangana, coastal Andhra and Rayalaseema were all under the Nizam’s (or Asaf Jahi), who came into power in 1724. However, after the second monarch, Nizam Ali Khan (1762-1803), signed the Treaty of Subsidiary Alliance with the British in 1798, the rulers were soon under financial duress as the state had to pay the British East India Company lakhs of rupees a year to maintain the foreign troops.

The Nizam’s government kept borrowing money from a bank (Palmer and Co) in the first half of the 19th century, which it could not pay back. Instead, the EIC paid-off the bank, and in return took away the Andhra and Rayalaseema regions away from the Nizams.

This was what led to Telangana and Andhra diverging in terms of culture and language, as the former’s Telugu was influenced due to its close proximity to Hyderabad and Urdu language (45.4% speakers in Twin Cities of Hyderabad and Secunder, as per the States Reorganisation Commission report, 1955).

The Andhra areas were merged with the British-administered Madras Presidency, with Chennai (then Madras) as its capital. Telangana, with its state-appointed landlords or Jagirdars under the Nizams, concentrated its wealth and capital in Hyderabad city, while the districts were fairly disadvantaged, even in the 20th century under the last Nizam Osman Ali Khan (1911-48).

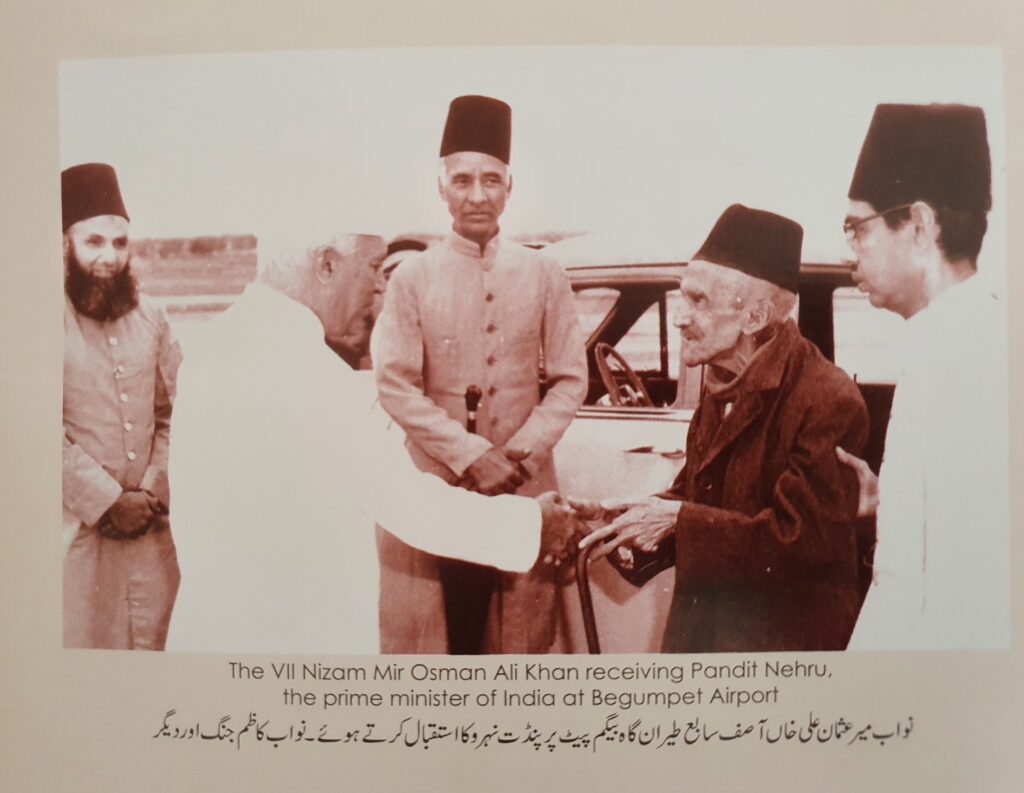

However it may be noted that under Khan, Hyderabad witnessed acceleration in development in the nearly four decades he was the ruler. Fast forward to 1947. When the British formally left India, it however gave princely states and their monarchs the option to join India or Pakistan, or to stay independent.

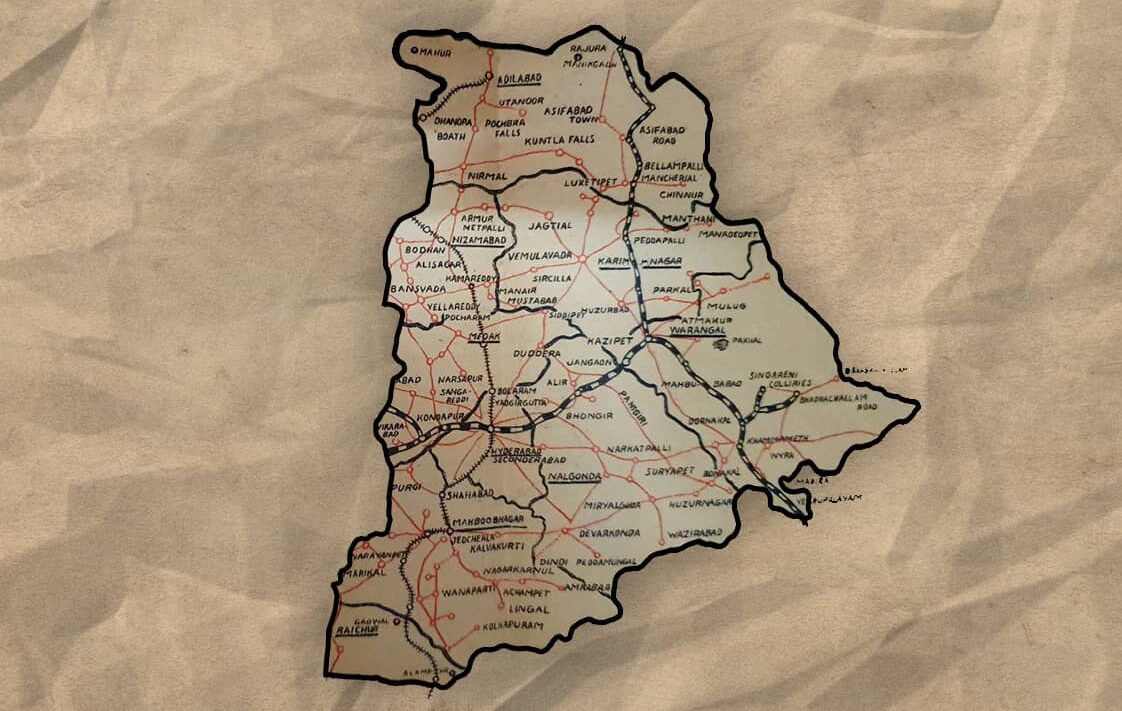

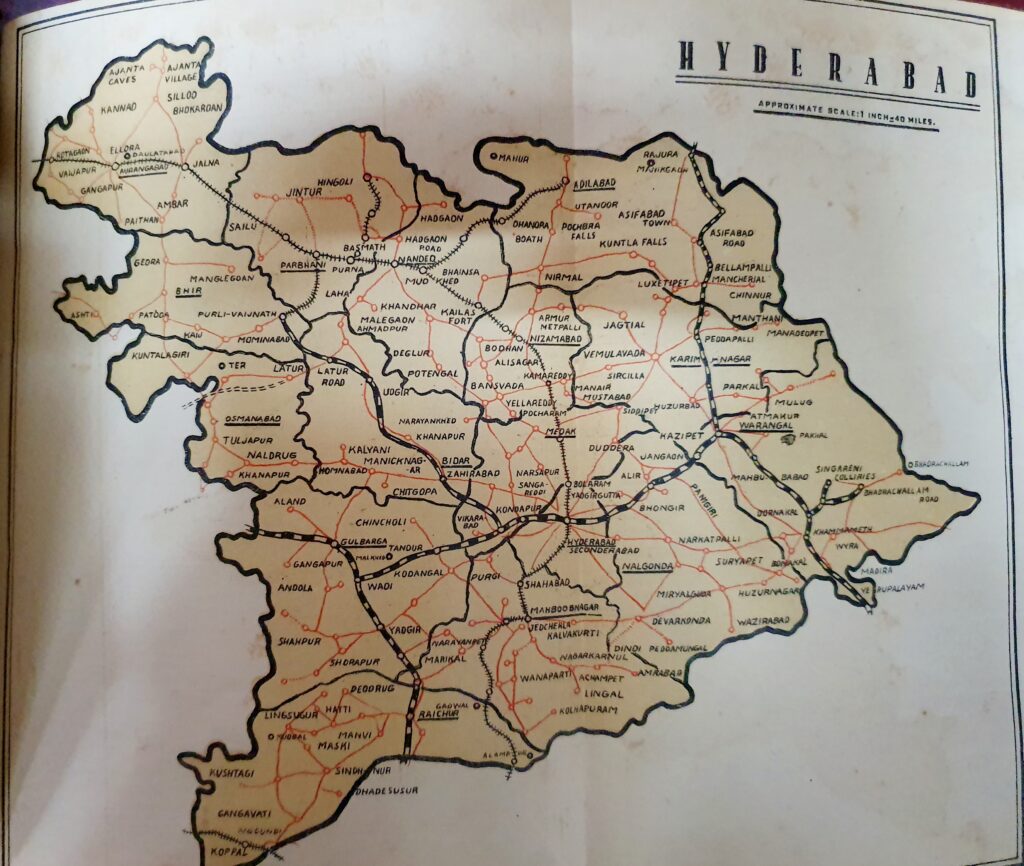

Osman Ali Khan was one of the handful of kings, like Hari Singh of Jammu and Kashmir, who wanted to stay independent. After all, he was a king of the largest princely state, Hyderabad, which comprised 16 districts in 1948, of which 8 were in Telangana, 5 in Maharashtra and 3 in Karnataka.

A year before 1947, extreme feudal oppression also led to the Telangana Armed Struggle (1946-51). Vetti Chakiri (bonded labour) was also commonplace in rural Telangana, wherein lower-caste folks were forced to service the higher castes and the landowning class.

Bonded labour and forced collections are believed to be the main reasons behind the uprising, which began in 1946, and officially ended in 1951, till the communists decided to contest elections. Some of the tallest CPI leaders from Telangana then were Makhdoom Mohiuddin, Ravi Narayan Reddy, Arutla Kamala Devi, Ch. Rajeshwar Rao, etc.

While that was going on, negotiations between the Nizam and the Indian government continued for a year. However, the government finally sent the Indian army to annex the Hyderabad state, which took place on September 17, 1948, in a military offensive called Operation Polo. For 18 months after that, the state had a military governor, after which it went to polls.

Post Annexation of Hyderabad to India & Mulki Rules

In the 1951-52 (first) general elections, the Congress comfortably managed to win in the Hyderabad state (which had 175 seats), while the CPI, riding on its popularity from the Telangana Armed Struggle (which was called off on October 21, 1951). Burgula Ramakrishna Rao was the state’s first (and last) chief minister.

The government even back then continued to implement the Mulki Rule, which essentially made a provision for locals to have access to jobs first.

The Mulki Rule was first promulgated (based on job guarantee demands by native residents of Hyderabad) in 1919 by Osman Ali Khan as Nizam, which stipulated that a person has to be a Mulki (different criteria to be met, especially for non-Hyderabadis) to be considered for any government service.

This was applicable to Telangana, and parts of Maharashtra and Karnataka that were under the Hyderabad state. The state’s medium of instruction was initially Persian and later (after mid-19th century) Urdu (during the time of Mulki rule). In the British administered presidencies, it was English. Post annexation of Hyderabad to India in 1948, these Mulki rules continued to exist even after the military governorship of Lt. Gen. JN Chaudhuri, who lead Operation Polo.

1952 Mulki Rule agitation, opposition to merger with Andhra

According to many old timers, especially those from the CPI who were part of the Telangana Armed Struggle, the Telugu speaking region was backward due to feudal oppression, and exploitation. Second, lack of (or much lower) education in English in the Hyderabad state meant that the government of India had to bring in officers from outside, especially from the Andhra region to work in the administration.

Locals from Hyderabad and Telangana felt outraged that jobs meant for them, under the Mulki rules, were given to non-state residents. This eventually led to the 1952 Mulki Rule agitation, wherein angry students even protested and reportedly damaged the official convoy of Burgula Ramakrishna Rao. In fact, his nephew and pro-Telangana votary from the CPI, B. Narsing Rao (passed away in January 2021), was one of the young leaders who participated in that movement.

That was in a way the first ever statehood movement, and it was over jobs. Aside from that, there were also feelings of being culturally ‘othered’ among Urdu speaking people (especially Muslims) Hyderabad. For the people of Telangana, they complained that their Andhra counterparts looked down and lampooned their Telugu dialect.

On Urdu and fear of its marginalisation

This would also reflect in the States Reorganisation Commission report from 1955. This is what it said on Urdu: “Three is one point which will have to be considered in consequence of a change in the present character of the State, namely, the position of the Urdu speaking people of the twin city’s of Hyderabad and Secunderabad to constitute 45.4% of the population. They seem to entertain the fear that if Hyderabad became the capital of either Telangana or Visalandhra, they would stand to suffer culturally and economically. There is some justification for this fear.”

It suggested “measures” that need to be adopted to give “adequate protection” to the “linguistic ,cultural and other interests of the large Urdu speaking people in the twin cities”.

Andhra state is formed, demand to share Madras as shared capital

By 1953, the Telugu speaking population from the Madras Presidency began demanding it own statehood, and on November 1, 1953, the Andhra state came into existence. However it had no built capital. Being part of the presidency, naturally its leaders wanted to share Madras with the Tamil speaking regions, but that demand was rejected.

Eventually, the idea of merging the Telugu speaking regions of Telangana and Andhra state was brought about. This was of course not going to go down well in Hyderabad, where there was already resentment against people of Andhra for taking up government jobs. In fact, what the States Reorganisation Commission said on this matter is very important to understand the imbalances that eventually came about after both the Telugu states were merged to create Andhra Pradesh on November 1, 1956.

What the States Reorganisation Commissiom recommended in 1955 on Telangana and disintegration of the Hyderabad State

While the Marathwada or Marathi and Kannada speaking (except Bidar) areas were to be merged with Maharashtra and Karnataka, the States Reorganisation Commission observations on Telangana are quite telling and interesting of how common languages does not work when there is socio-economic inequality.

After going through the merits and demerits of merging Andhra and Telangana, and stating that the case for “Vishalandhra thus rests on arguments which are impressive”, the report also noted: “The considerations which have been urged in favour of a separate Telangana State, however, not such as may be lightly brushed aside.”

It took of the fact that “some” leaders from Telangana “seem to fear that the result of unification will be to exchange some settled sources of revenue, out of which development scheme may be financed, for financial uncertainty similar to that with which Andhra is now faced”. Before the merger, and after 1953, Andhra, without a capital, had a lower per capita income than Telangana, which from an administrative point claimed “to be progressive”.

The Commission, while stating that there are benefits of bringing Telangana and Andhra regions for sharing the Krishna (over which both states are today vying for a higher share) and Godavari river basins, and “suitability” of Hyderabad as capital, was still not convinced about the merger. It also noted that Andhra leaders were also ready to provide adequate safeguards, like a pact for local job quotas, if both states merged.

The recommendation was against the merger and creation of AP

However, the States Reorganisation Commission noted that all the promises and pacts will however not “prove workable or meet the requirements of Telangana during the period of transition”. In its final conclusion, it said:

“After taking all these factors into consideration, ‘we have come to the conclusion that it will be in the interests of Andhra as well as Telangana, if for the present, the Telangana area is constituted into a separate state, which may be known as the Hyderabad state, with provision for unification with Andhra after the general elections likely to be held in or about 1961, if by a two-thirds majority the legislature of the residuary Hyderabad State expresses itself in favour of such unification.”

It added that Telangana if public sentiment in Telangana “crystallises” against the unification, it will “have to” continue as a separate unit. So what does this mean? Perhaps Andhra would have built itself a new capital, and Telangana in turn would have functioned as it was with Hyderabad as its capital.

However, against this, the Indian government decided to go ahead with the merger in 1956 (many say due to political compulsions and compunctions), and the issues with regard to jobs and cultural oppression in Telangana continued, leading to the 1969 statehood movement first. Led by Marri Chenna Reddy, it would be compromised as he joined the Congress eventually.

However, it was revived once again by incumbent chief minister K. Chandrashekhar Rao in 2009, a after former CM of the joint Andhra Pradesh state YS Rajasekhara Reddy died in a helicopter crash the same year