The West Indies has produced some of the legendary names of cricket such as Sir Garfield Sobers, Sir Vivian Richards, Brian Lara, Malcolm Marshall, Andy Roberts, and many others. Nowadays it is difficult to imagine that at one time cricket in the West Indies was dominated by whites and blacks were kept out of the game.

Cricket was introduced to the Caribbean islands by English soldiers stationed there. The well-to-do classes played the sport avidly but the poorer sections had no role. However, two very talented black players opened the eyes of the local population as well as the rest of the world, to the vast amount of cricketing merit that existed among the black population.

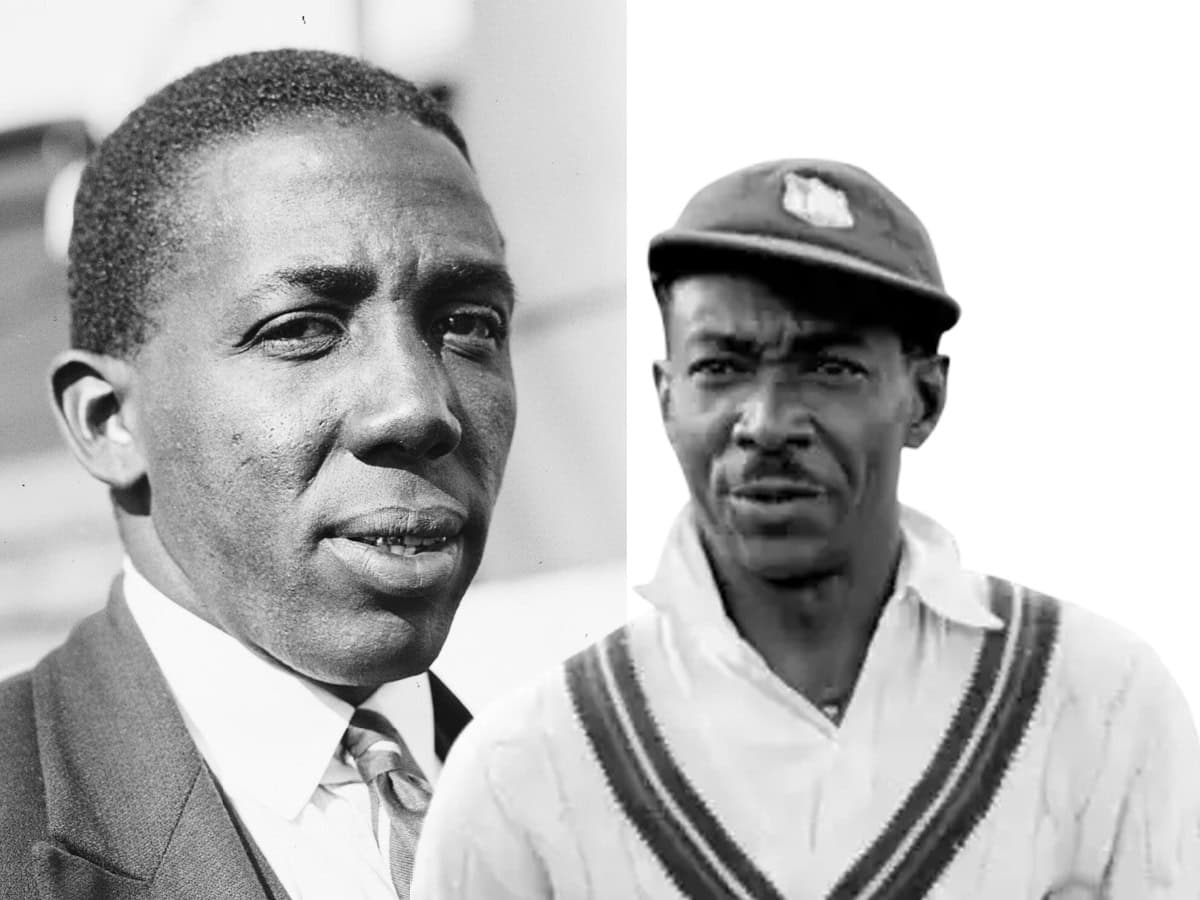

The two were Learie Constantine and George Hedley. The former was a descendant of slaves who worked on a plantation. When he grew up, Constantine felt unhappy with the lack of opportunities for black players in his home country of Trinidad. He decided to go to England to play as a professional cricketer. He played for Nelson Club with distinction from 1929 and also represented the West Indies in Test matches.

Racial divide in cricket

In the 1920s Cricket in Trinidad and Tobago was divided along racial lines. But the white captain of the Trinidad team, Major Bertie Harrigan, recognised Constantine’s talent and selected him to play in the country’s match against British Guiana. From there his cricket career took off.

Constantine represented the West Indies when it toured England in 1928. Wisden praised his unorthodox batting and his excellent fast bowling. As a fielder he was fantastic. Thereafter he was selected for the team to tour Australia in 1930. He went on to become one of the earliest legendary cricketers of the West Indies.

He got a contract to play for Nelson Club in England and used his spare time to acquire a law degree and took up cases of racial discrimination. On one occasion he and his family were denied entry into a popular hotel because they were black. He took the hotel to court and won the case.

Knighted by Queen Elizabeth

After many years of hard work for racial equality, his efforts saw the Race Relations Act being passed in Britain in 1965. He was knighted by Queen Elizabeth and was thereafter called Baron Constantine. He became the first black member of the House of Lords. It was a great achievement indeed for a descendant of slaves.

Headley was called Black Bradman

George Headley, who lived in Jamaica, played in only 22 Test matches because the Second World War interrupted all sports activities. But he was nevertheless hailed as one of the greatest batsmen to have emerged from the Caribbean nations. Cricket experts were so impressed with his batting technique that they nicknamed him The Black Bradman.

But his admirers in the West Indies were not satisfied with that name. They felt that it lowered his status. So they responded by referring to Don Bradman as The White Headley. Bradman ranked in 1988: “I am proud that they dubbed him the ‘Black Bradman’. But perhaps it should have been in reverse.”

The records

Headley eventually ended up scoring 2,190 runs in Test cricket at an average of 60.83 per inning. He also compiled 9,921 runs in all first-class matches at an average of 69.86. He was chosen as one of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year in 1934.

A question of race

For reasons related to class and race, it had been unthinkable for the West Indies to appoint a black Test captain, but after the Second World War, there were social and political changes in the Caribbean. Headley was appointed as one of the three West Indian captains for the series against the England team which toured the Caribbean in 1948.

Headley was given the captaincy for the first and fourth Test matches, while two white players–Gerry Gomez and John Goddard were given the captaincy of the second and third matches.

Success recognised beyond cricket

But his success and reputation were equally significant beyond the confines of a cricket field. Former Prime Minister of Jamaica, Michael Manley said that Headley’s rise to success heralded a time of political awakening in Jamaica when the black majority of the population became determined to end the minority rule of landowners and challenge racism.

So not only did Constantine and Headley break records on the cricket field, they also broke the shackles