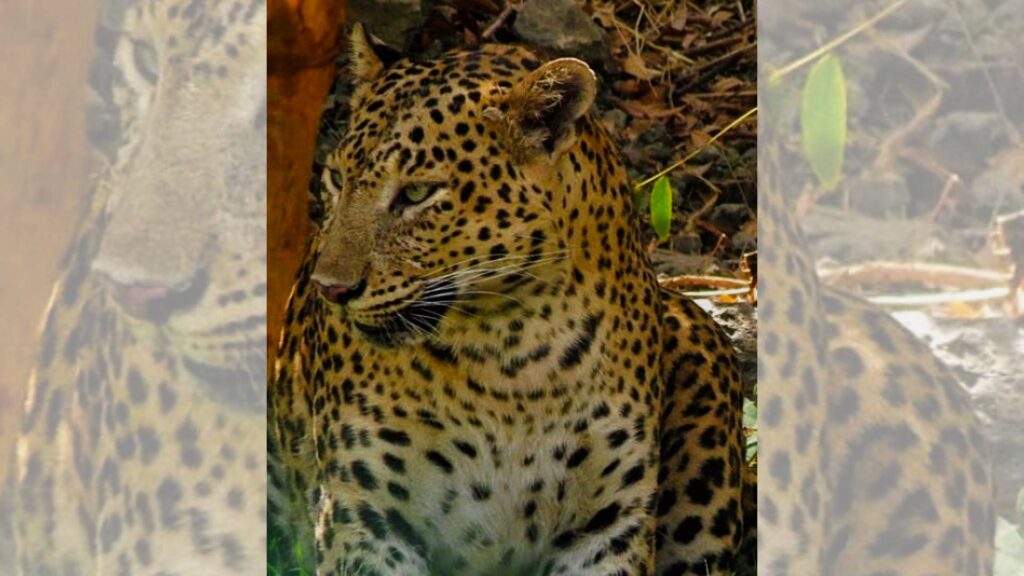

In the shadows of skyscrapers and the tantrums of traffic, a supple spotted ghost moves with silent purpose. This is no myth — it’s the Indian Leopard, one of the most adaptable and misunderstood big cats on earth. And nowhere is its paradox more vivid than in Mumbai’s Sanjay Gandhi National Park. Hemmed in by high-rises, slums, highways, and film studios, this 100-square-kilometre jungle hosts nearly three dozen leopards that live undetected in the very heart of the mega-metropolis.

These cats are not intruders. They are survivors — stealthy, intelligent, and essential. Navigating narrow lanes, railway tracks, and open drains under cover of darkness, they hunt feral dogs, wild pigs, and rodents. In doing so, they perform vital ecological services: curbing disease vectors, controlling urban pests, and even reducing roadkill by shifting prey dynamics. They are not threats. They are, ironically, the invisible custodians of a city that barely notices them.

But Mumbai is not alone. Across India, from the ICRISAT campus of Hyderabad and Infosys at Mysuru to the green patches outside Pune, Bengaluru and Gurugram, etc. Leopards are appearing more frequently in human spaces. This isn’t due to some evolutionary curiosity — it’s desperation. Their forest homes are being flattened, mined, fenced, and paved. As wild territories shrink and ecology fragments, leopards are forced to adapt or vanish.

A few months ago, a leopard was spotted at the Infosys campus in Mysuru, sparking a media frenzy and a 10-day search operation involving drones, cages, and camera traps. Employees were told to stay indoors. The leopard, meanwhile, never attacked anyone. It was merely seeking shelter. In such moments, we must ask: who is truly encroaching on whom?

Predators with purpose

My first encounter with a leopard was thirty years ago while on a jungle safari at Gir National Park and it was in plain sight and yet invisible as it was hugging the ground. Once we sighted the cool cat, it simply vanished into thin air. Leopards are not just wildlife — they are keystone species, meaning their presence (or absence) dramatically shapes entire ecosystems. In India’s forests, from the dry teak woodlands of Madhya Pradesh to Andhra Pradesh or elsewhere the leopards regulate herbivore populations like deer and wild boar. This prevents overgrazing, which in turn protects soil, conserves water, and preserves forest health. Remove the predator, and the entire ecological pyramid begins to crumble.

Unlike lions or tigers, leopards don’t demand vast territories or exclusive diets. They are the ultimate survivors — equally at home in the dense undergrowth of Himalayan foothills or the scrublands of Telangana. This flexibility makes them both marvels of evolution and the first to encounter humans when forests are flattened by, we humans.

City cats: A delicate dance

In urban and semi-urban settings, Leopards are increasingly becoming reluctant cohabitants. Their presence on the fringes of cities isn’t merely incidental — it’s often beneficial. In places like Delhi’s Ridge or Pune’s outskirts, Leopards prey on wild pigs that damage crops and feral dogs that spread diseases. By keeping these pest populations in check, they reduce risks like rabies, anthrax, and food chain imbalances.

Yet public perception remains warped. The media paints every sighting as a threat. Leopard attacks, statistically rare, are often triggered by fear, cornering, or misjudged responses — not predatory intent. These are not man-eaters; they are displaced residents by humans.The real challenge lies in our response. Panic-driven rescues, relocations, or retaliatory killings only worsen the cycle. What we need is calm, informed coexistence — built on science, not superstition.

Vanishing corridors, fractured futures

Despite their adaptability, leopards cannot survive without space. And space is what we’re taking fastest. Highways bisect ancient corridors. Resorts pop up inside protected zones. Mining, monoculture plantations, and real estate continue to consume leopard habitats at a staggering pace. The result? More conflict, more displacement, more danger — for both animals and people.

This is not just about saving a species. It’s about saving ecological sanity. Every forest we lose is a blow to climate stability, water security, and biodiversity. When we erase the paths of predators, we sever the veins of ecosystems. And it’s not just habitat loss — it’s a breakdown of ancient balances. Leopards, like all wildlife, have evolved to coexist with humans over millennia. Tribal folklore often reveres them; rural practices once respected their presence. But modern development has forgotten this pact. We build over silence, and wonder why the wild screams back.

A future worth fighting for

Leopard conservation must be more than reactive—it needs reimagination. Urban planning should incorporate wildlife crossings, green corridors, and buffer zones. Infrastructure must account for ecological movement, not just human convenience. There are glimpses of hope. In Maharashtra, underpasses built along highways have successfully allowed safe animal crossings. Local communities, when engaged and empowered, have become protectors rather than victims — turning conflict into cooperation. In some villages, people now report leopard sightings not with fear, but fascination. Like in Jawai and Jhalana in Rajasthan as I have visited both these locations. Education is the key. When people understand that leopards are not lurking predators but ecological allies, perspectives shift. Stories, traditions, and science must be woven together to build this new ethic of coexistence.

The leopard’s lesson

The leopard isn’t just a creature of the wild. It’s a mirror. In its resilience, we glimpse our potential to adapt. In its fading territories, we see the consequences of our unchecked expansion. And in its silence, we hear a call — not just to conserve, but to recalibrate. To preserve the Leopard is to protect more than a species. It’s to defend the very threads of balance that hold our living world together — spotted, silent, and sacred.