Historically speaking, food has always worked as fodder for other forms of art. However, it has also been denied the status of art for unexplained reasons. Dalit artist Sri Vamsi Matta, while primarily trying to reclaim narratives of oppression as a part of the community, is also attempting to give food the status of art that it deserves.

“We are not stories to tell. We are full human beings with choices, emotions and motivations like others,” remarked theatre artist Vamsi, criticising Dalit accounts written by upper-caste folks in the past. Be it movies or other forms of art and literature, this justifiable critique has time and again made its way into the art scene.

Vamsi, like other Dalit artists worthy of their name, makes it a point to note that a Dalit person’s account, their very story, cannot be reduced to solely their oppression, which is what we often see in popular media.

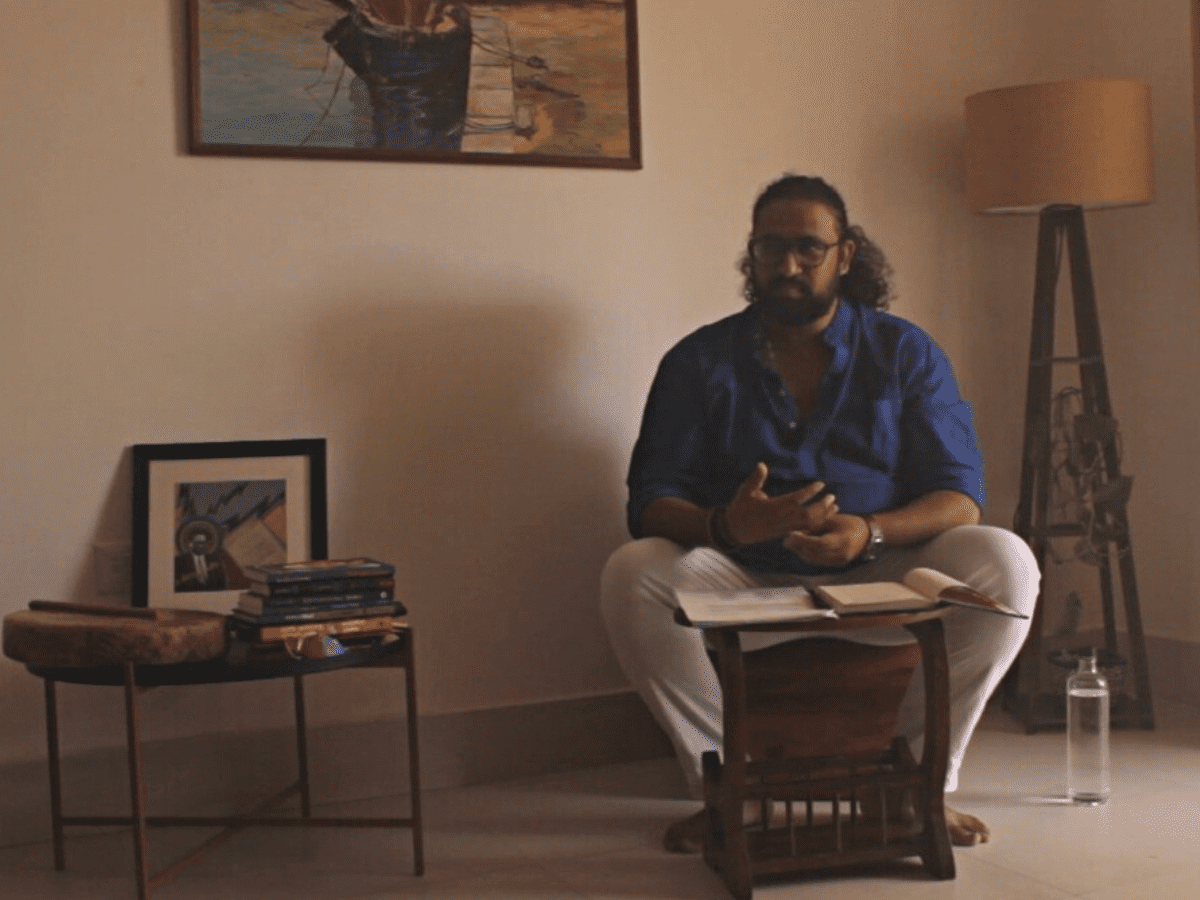

Sri Vamsi Matta has been a theatre artist for over ten years now. Although he was initially a B.Sc student at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore, his love for theatre steered him off the science course. While Vamsi has written and acted in innumerable plays, more recently, his bringing together of food and theatre under the performance banner ‘Come eat with me’ has gained popularity.

What is Come eat with me about?

In his performance, he goes to people’s houses and cooks food for them with the aim of normalising Dalit cuisine, which historically speaking, has been viewed with disdain and disgust by upper-caste groups. Much like his food, the stories which accompany his ‘Come eat with me’ performance are personal.

In a forty-minute conversation with Siasat.com, Vamsi brings up stories replete with oppression. The stories, his own and those of other Dalits, trace how casteism dips into and bit-by-bit eats away a Dalit person’s sense of self-respect and adversely affects their identity.

“I remember reading Endapalli Bharathi’s account of the discrimination her brother faced in third grade. The smell of the lunch he took with him to school prompted the teacher to ask if he was eating beef. When he answered in affirmative, the teacher remarked, “Yeddu mamsam tintunavu, anduke ni burra yeddu laga tayyaraytundi (You are eating buffalo meat and that is exactly why your brain is starting to resemble one)”. After that Bharathi’s brother never went back to school, said Vamsi.

Vamsi makes it known to this reporter that while his own life experiences and the discrimination he has faced have made life difficult, these aren’t his stories alone. Even in his theatre performances, he time and again invokes accounts of other Dalits.

This sharing of stories, along with the food he cooks, is what makes theatre an honourable profession for him. Further, Vamsi is uncomfortable associating himself with conventional theatre. He says, “A major part of theatre has been written, directed and enacted from a cis-gender, heteronormative, savarna gaze.”

Whose theatre is it anyway?

At a time when theatre artists are using their art to speak against the establishment, Vamsi has carved out a space to do the same and more. He shuns traditional language and forms even as he retains the essence of theatre. In his performances, Vamsi converses time and again with his audience, thus breaking the fourth wall.

“Who decides what qualifies as a performance? Many critiques have remarked that what I do does not qualify as one. Cooking is performance. You have to put the ingredients in at the right time. If not, the dish is ruined. I carry with me a bunch of stories that I discuss. There is a script, the sound is modulated, there are costumes involved. What would this be if not for theatre?” he asks.

During the entire conversation with Siasat.com, Vamsi maintains an unnerving calm. Even his pauses come across as thoughtful and measured. At one point while discussing theatre, he chuckles and says, “Who decides what rules are? Only those in power.”

The mind of the artist:

For Vamsi, his art is a way of ensuring that he tells his own story and no one else does it for him. But aside from the self-assertion, he also wants it known that there is great joy in sharing food, sharing stories. When asked about his heroes, he promptly invokes Dr BR Ambedkar. But also discusses his father, Telugu writer Dr Matta Suguna Rao who heavily influenced his thinking.

Even as he speaks about the literature which added to his thoughts on caste, (Sujatha Gidla’s Ants among Elephants, Yashica Dutt’s Coming out as a Dalit and Kalyana Rao’s Antarani Vasantam (Untouchable Spring), he acknowledges that the whole process can be highly exhausting. “I do get tired,” he remarks in response to the question posed. “However, there is a certain power in arresting people with conversation, having them listen to you and understand where you are coming from,” he says.

As far as Vamsi is concerned, his chief goal is to change the gaze through which people see food and subsequently Dalit lives. “We need to bring caste back into living room discussions. I want to talk about the difficulty and the fear surrounding beef consumption. We need to stop being so hush-hush about caste,” he adds.

When asked if attempting to solve a systemic problem at a time when theatre might fizz out is disconcerting, Vamsi simply remarks that theatre is not dying and will continue to thrive. “However, if casteist gate-keeping, denial of grants continue, the artist might very well die.”