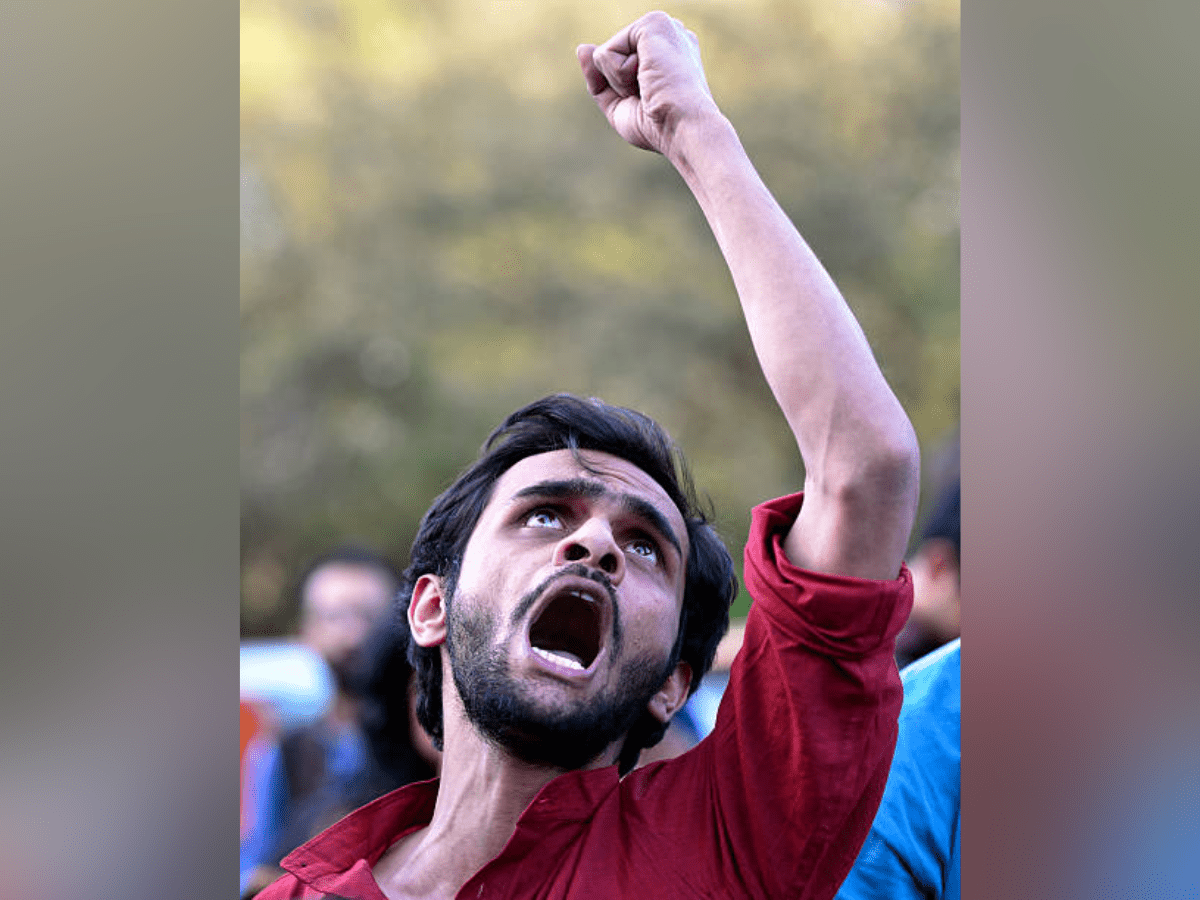

September 13, 2022, marks two years since Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) scholar and student activist Umar Khalid was imprisoned under the draconian Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). Khalid has been accused of starting the northeastern Delhi riots of 2020 and despite multiple appeals to the court and a lack of concrete evidence, the case continues.

Khalid was arrested along with Natasha Narwal, Devangana Kalita, and Asif Iqbal Tanha for protesting against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) as well as the northeast Delhi riots between February 23, 2020, to February 26, 2020, which took away 53 lives and injured hundreds.

Among the dead, 40 were Muslims and 13 were Hindus.

According to the Delhi Police charge sheet, Khalid allegedly made two speeches that “instigated” people to come on streets and block roads. This happened simultaneously during former US President Donald Trump’s visit to India in February 2020, just before the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic hit the country.

The Delhi Police alleged that Khalid was ‘part of a conspiracy to defame Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government’.

Two years of jail time can be a lonely journey. The desire to be free again can feel like a black hole especially when the question is how long.

The Wire had the opportunity to look into the mind of the political prisoner. Khalid had replied to a letter by one of his admirers Rohit Kumar, who on September 12 this year had written an open letter to the former.

With the consent of Rohit, The Wire published Khalid’s response. A letter that gives a sneak peek into what goes on in the mind of a man who has been jailed over his speeches, demanding to be treated equally, and often finds himself in dark spaces when he dwells on thoughts of freedom and a chance to breathe the air beyond the tall walls.

The letter reads;

Dear Rohit

Thank you for the birthday and Independence Day greetings and thank you for writing to me. I hope you are doing fine. I am glad I was able to read your open letter even within these closed perimeters.

In the letter, Khalid talks about “rehaai parchas” – the release orders. He says that every evening, after sunset, the jail authorities announce the names of those who will taste freedom after many months or years. He mentions one day, he hopes to hear his name too.

For two years now, I have been hearing this announcement every night- “naam note karein, in bandi bhaiyon ki rehaai hai” (note the names, these inmates are being released). And I wait and hope for the day when I would hear my name. I often wonder, how long is this dark tunnel? Is there any light in sight yet? Am I near the end, or am I only midway through? Or has the ordeal just begun?

Khalid mentions the recently celebrated Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav and wonders if Azadi is real. Sitting outside his cell along with other inmates, he watches colourful kites flying over the sky reminiscing about his childhood and then wondering how the country landed, and where it did.

Do people not see any similarity between the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA) – under which we are languishing in jail – and the Rowlatt Act, which the British used against our freedom fighters? I feel particularly baffled by the fact that many of us, and many others like us, are being detained without trials for extended periods of time without any visibility on when our trials may begin.

He goes on to talk about how ‘lies’ are dangerously being manufactured every minute, every second in order to not let ordinary citizens think. He says how the media has acted like the Devil’s advocate, making him look like an enemy of the country. A man who is only bothered about ‘his people and will not stop spilling blood until every one of the ‘others’ is destroyed.

The English newspapers have tried to maintain the pretence of objectivity, but most of the Hindi newspapers – which over 90 percent of the prisoners depend upon for their daily dose of news – have thrown all journalistic ethics to the wind. They are pure poison.

One morning, a newspaper headline in a Hindi daily screamed, “Khalid ne kaha tha bhashan se kaam nahi chalega, khoon bahana padega”. (‘Khalid said speech not enough, blood must flow’) Two days later, the same newspaper came up with a headline even more sensational than the previous one, “Khalid chahta tha Musalmanon ke liye alag desh”. (‘Khalid wanted a separate country for Muslims’) I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. How do I persuade those who are consuming this poison every day?

Khalid’s letter is not just all about complaints. Khalid looks at some positive things in life which he never thought would begin on that side of the wall.

For starters, Khalid sleeps well, and on time. A person whose attention span was not less than a tweet, now reads voraciously. Khalid says he is happy that one freedom he has is the freedom from social media. Quitting smoking is another feather in his cap.

On January 11, 2022, Outlook published a portion of Khalid’s personal diary. The article starts with how Khalid is as excited as a little boy travelling in a tram for the first time, looking at the passing of life.

I could see people going to their offices and children to their schools. There were people in cars, buses and on roads. Some were immersed in their phones, while others were talking to each other. There was no one watching over them. They were free to go wherever, talk to whomever.

It was a fascinating sight—the sight of free people. I was reminded of the past when I too, like the people I was staring at, had been free.

Khalid mentions Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o prison memoir wherein the latter compares to time spent in jail as an endless loop of — you wake up, you eat, you defecate, you sleep. A daily monotony – says Khalid.

Khalid also talks about the hanging by a thread between hope and hopelessness.

You always remain hopeful that some judge will see through the absurdity of the charges, and set you free. At the same time, you keep cautioning yourself about the perils of nurturing such hopes. The higher your hopes, the higher would be the distance from which you would come crashing down.

Khalid talks about how loneliness can turn a person bitter. To top it all, receiving comments from other inmates about religion, about what they have seen, read and heard about you as described by certain sections of the media, and how they perceive you and your family due to your religious identity, even though you do not identify with it.

Khalid talks about conversations with inmates who without any hesitation would ask him about how many wives his father has and how many he intends to have in his life. Questions about why Muslims support the Pakistani cricket team. And if you try to reason out or explain to them the bigotry they are subjected to which they are unaware of, the reply, “Arey kya galat bola, aap logo mein toh aise hi hota hai na.”

Khalid compares how he cannot hide from the bigotry and prejudice of Muslims as compared to when he was free.

Till now, hate came from a distance, usually from TV and mobile screens. I always had the option of switching it off, if it got too much. My immediate circle—the people I spent time with in real life sheltered me from hate.

Jail has removed this distance. Now hate and prejudice are up close and in my face. There is nobody to shelter me, and nobody to confide in.

But he goes on to say that the comments or questions he faces daily are not from people who have an agenda, but from people who have a good heart and do not mean bad for you. People who would not hesitate to share their food or ask for legal advice.

The article concludes with a Faiz Ahmad Faiz couplet, about finding strength behind the barbed wires of the tall walls.

Dil se paiham ḳhayāl kahtā hai

itnī shīrīñ hai zindagī is pal

zulm kā zahr gholne vaale

kāmrāñ ho sakeñge aaj na kal

jalva-gāh-e-visāl kī sham.eñ

vo bujhā bhī chuke agar to kyā

chāñd ko gul kareñ to ham jāneñ

“Though they may concoct tyranny’s poisons

They will have no victories,

not today, nor tomorrow.

So what if they douse the flames

in rooms where lovers meet?

If they are so mighty,

let them snuff out the moon.”