The boards were established only in 1954. Until then requirement was that the mutawallis or trustees of each waqf deposit with the district judge of the district, information as regards the waqf under their control. This led to an unsatisfactory mechanism denuded of control. It was realized that several mutawallis and trustees were dealing with waqf properties improperly in violation of the waqf-name, especially since there was no penal consequence associated with the non-reporting of required information to the district judge. It was considered necessary to have better management and therefore the Waqf Act of 1954 postulated the creation of such boards. It is fallacious to assume that that was when waqfs were created, because their origin lies in antiquity and there have been Waqf Acts of 1913, 1923, etc. before the 1954 Act was promulgated. In India, the history of Waqf can be traced back to the early days of the Delhi Sultanate when a ruler dedicated two villages in favour of the Jama Masjid of Multan and handed its administration to a caretaker or mutawalli. As the Delhi Sultanate and later Muslim rule flourished in India, the number of waqf properties kept increasing.

A great deal of misinformation is found in respect of the Waqf Act of 1995. For instance, sec. 40 postulates that the Waqf Board of a State is empowered to decide whether a property is a waqf. A GCLS blog states sec. 40 of the Act vests power with the Waqf Board to decide as to whether a property is waqf property or not. It argues the provision is ambiguous, fails to adhere to principles of natural justice, and alleges the absence of “compensation to affected parties in line with the principle of eminent domain”. What is sec. 40?

S. 40 says (1) The Board may itself collect information regarding property which it has reason to believe to be waqf property and if any question arises whether it is or not, it may, after making such inquiry as it may deem fit, decide the question. (2) The decision shall, unless revoked or modified by the Waqf Tribunal, be final. (3) Where the Board has reason to believe property of any trust or society registered in pursuance of the Indian Trusts Act or under Societies Registration Act or any other Act, is waqf property, the Board may hold an inquiry and if after such inquiry the Board is satisfied that such property is waqf property, call upon the trust or society, as the case may be, either to register such property under this Act as waqf property or show cause why such property should not be so registered: Provided that notice of the action proposed to be taken shall be given to the authority by which the trust or society had been registered. (4) The Board shall, after duly considering such cause, pass such orders as it may think fit and the order so made by the Board shall be final unless it is revoked or modified by a Tribunal.

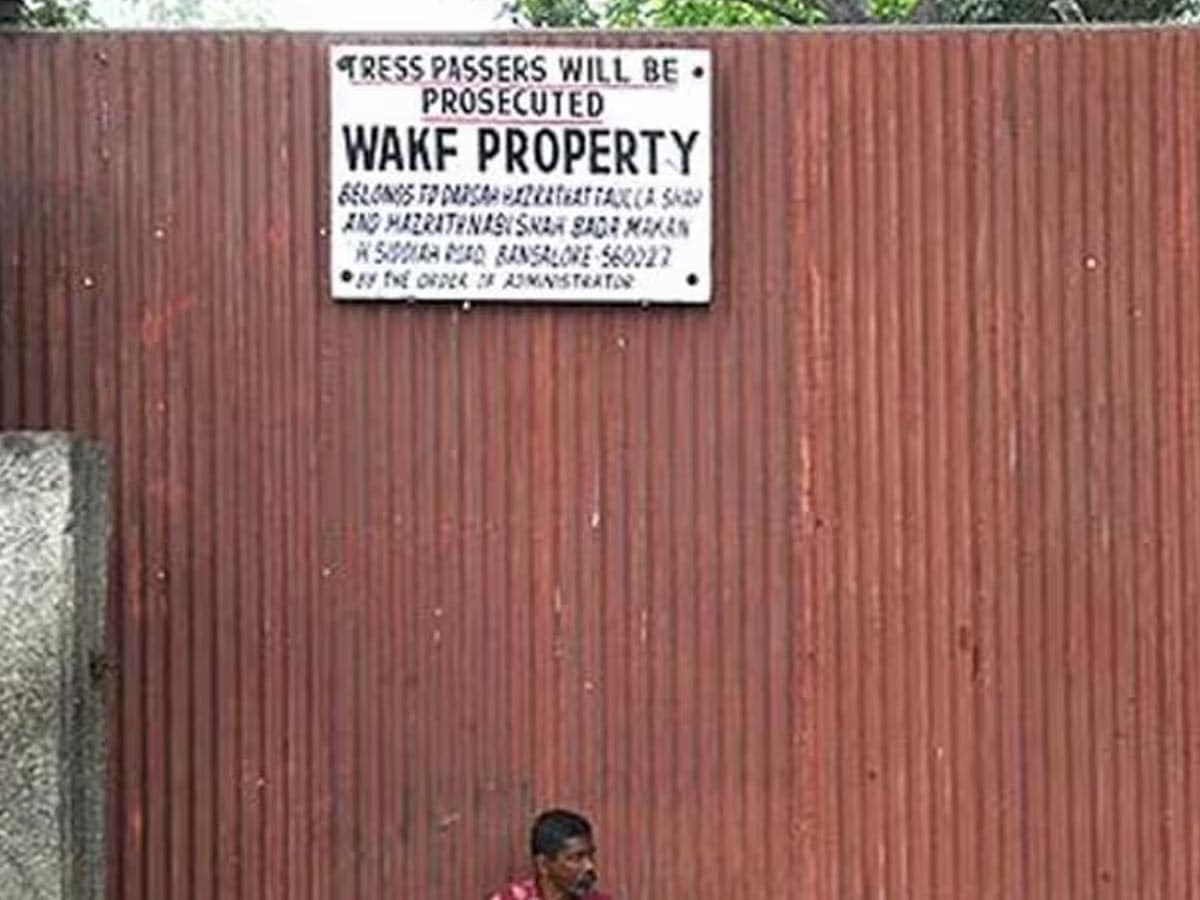

For the information of readers, Waqf Boards have no properties at all, except the buildings where they may have their offices if at all the specific Board owns that building. All waqf properties are the properties of individual waqfs, none of them owned by the Waqf Board. Properties of waqfs, societies, and trusts remain properties of waqfs, societies, and trusts, and never become “properties of” the Waqf Board.

This crucial aspect seems carefully brushed under the carpet. It is thus seen that the objective is not to take over properties of anybody and everybody but only to bring under the supervisory control of the Board only such properties held by trusts or societies the objectives of which trusts or societies are “religious pious or charitable under Islamic law” that being a sine qua non for a property to be considered waqf. It is noteworthy that there is no taking over of property at all and only the supervisory role is introduced besides which, as the underlined words show (may) the institution, whether trust or society or otherwise, is allowed to show cause and only then a decision arrived at. This throws up in stark contrast the fallacious argument of the blog that the principle of audi alteram partem (hear the other side) is violated, which is again an incorrect and misleading statement. What is more, notice is given not just to the institution (show cause) but also to the authority that registered the institution which is the State. Finally, the Waqf Tribunal is a judicial adjudicating body, headed by a District Judge cadre judicial officer, deciding whether the registration should be upheld or not, and not, as the blog incorrectly suggests, whether the property “belongs to the Waqf or not”.

If you as a recipient trustee of property gifted, are required to enter it in a register of gifted trust properties, is it thereby “taken away” from you? Hardly. It continues to belong to the trust, you remain its trustee, the only difference being that its entry is found in that register. You continue to manage it, do whatever the instrument of trust requires you to, and nothing changes that. As trustee your powers are unchangeable, as declared by the instrument of trust. As the supervisory body over institutions under its supervision, even the Waqf Board can neither do, nor require you to do, anything at variance with that documented regime. The State, as authority over the Boards, and Courts, as authority over even the Government, are also similarly bound. Is it any different for Hindu endowments? In fact as being a department of the State the Endowments Department has power to act directly, the Waqf Boards do not, and have to seek assistance of the Collector to enforce rights. So what exactly is the complaint?

Stating erroneously the section does not provide for opportunity for parties to be heard, the blog points out that in State of Andhra Pradesh v A.P. State Wakf Board & Ors., the Supreme Court held an inquiry under Section 40 could only be held after hearing the affected parties. So how is it unfair, as mysteriously if not mischievously suggested?

Claiming “lacuna in the section” the blog argues “if properties are being taken from individuals by the Waqf Board, explicit provision of hearing to affected parties should be mandatory”. One, we have seen properties are not taken away: registration with the Board is sought, since the institution’s activity is “religious pious or charitable under Islamic law”. Two, explicit provision of hearing is very much present.

The blog proceeds to state, “Looking at the Waqf Act, there seems to be no plausible explanation as to why principles of natural justice have been conveniently side-lined in direct violation of constitutional principles”. Which principles of natural justice are side-lined and which constitutional principles are violated? I see none.

A false contrast is sought to be projected by reference to NHAI Act, 1956, sec. 3A, which requires that where land is to be acquired, under the Official Gazette it is to be notified… the blog omits to note that in the case of the Waqf Act sec. 40, no land is being acquired or taken away. The blog aggravates the matter by saying NHAI Act mandates compensation, whereas the Waqf Act does not, again omitting to note that in the NHAI case property is taken away for making a highway, whereas in the Waqf case, nothing is taken away at all. Are these serious errors inadvertent, or is the “scholarship” involved suspect?

The blog argues “Eminent Domain”, State of Bihar v Maharajadhiraja Sir Kameshwar Singh & Ors., … M/s. Delhi Airtech Services v State of UP, …“compulsory acquisition of property upon payment of compensation to the affected individuals”… how it fails to notice that nothing is taken away, compulsorily or otherwise, in the Waqf case is a mystery. Or maybe in the present atmosphere, it is not one.

Shafeeq Rahman Mahajir is a well-known lawyer based in Hyderabad. He writes on a variety of legal and constitutional issues.