Despite being primarily perceived as a demonic, grotesque and religiously and socially deplorable way to seek hedonistic pleasure, promiscuity or voracious sexuality bolsters female power of self-assertion. It is an act of empowerment that stemmed from how the nubile female body cast a spell on men.

It creates a space not inhabited by the sense of triumph or guilt. The unbridled desire to be loved or accepted is the most significant female hope that impels women to seek solace from being continually in the company of men. Sexual insatiability or addiction to male attention does not mean looking for love in all the wrong places; it is an act of self-actualization which is not an extension of sexual ambition.

Lewdness is not just an aberration or a symptom of a mental disorder; it is deeply mired in the psyche as human life draws its sustenance from a relationship that continuously oscillates between intimacy and apathy. Togetherness, either in the form of friendship or marriage, does produce anxiety and stress which, can only be addressed by seeking the involvement of a third person, and it provides a much-needed counterbalancing force. A relationship is constantly plagued by anxiety, insecurity, and emotional closeness, and according to Thomas Fogarty, a twosome is inherently unstable and forms a threesome. It runs all along in life, no matter, one is involved in which kind of relationship. In the period of stress, outside intervention lightens the burden. Charles Dickens and D.H. Lawrence have poignantly portrayed various shades through female characters, especially Nancy (Oliver Twist, 1838) and Lady Chatterley (Lady Chatterley’s Lover, 1928), and both characters are unapologetically promiscuous.

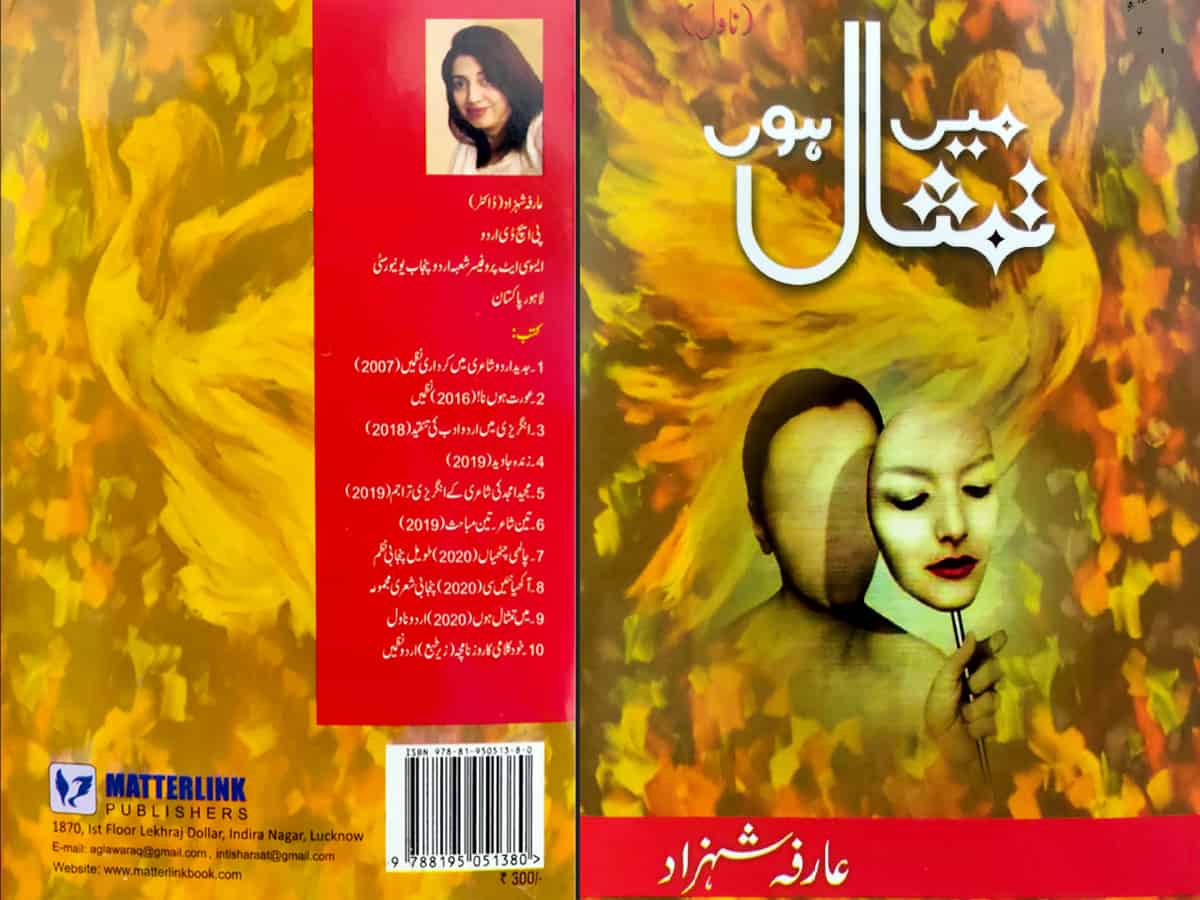

Despite having a reasonably significant tradition of fiction writing, hardly any attempt is made by any Urdu writer to produce a gripping narrative of the fervour of passionate love seeking diversity, not fixity. It is left to a celebrated author Arifa Shahzad to supplement what has been missing. Her latest novel Mein Timsaal Hoon (2021), having the deceptive appearance of sex tell-all, tells a tantalizing, not titillating tale of a libidinous life that carries a vanity through which a woman can understand herself beyond the terms imposed by the patriarchal society. The novel reels off a pulsating tale spread over seven love affairs.

The pulsating episodes do not put before us a story of an ever-salacious seeking pleasure wicked or psychologically damaged Woman; it takes us into curious worries of relationship. It is divided into seven succinct chapters based on the diary of female protagonist Timsaal, and her unrelenting quest for satisfaction and lack of it is intonated with equal vehemence.

The novel begins with an affable email sent by a psychiatrist, Dr Ahshan, whom Timsaal approached when the last (seventh) split up left her completely exasperated. In order to pull out her from deep-seated depression, the doctor exhorted her to jot down the departing note, never to be sent to the beloved. She might be forced to write more, not to- be- sent letters that will assuage her overwhelming sense of loss or rejection, and it will restore normalcy. It irked Timsaal, who is a creative writer, and she retorts, “You seem to be an off-the-wall psychiatrist as you are not aware that the first love can never be the last as the seventh could be the first love. One cannot write the last letter to the first love. Love cannot pull down itself, be it first, second, or last.”

Explaining why she descended into promiscuity, Timsaal asserts, “Woman has always been seen or depicted as the beloved, but I have been the lover since time immemorial. I revolted against the gender-specific role; hence I had to bear the brunt of the separation time and again. I hardly forget any of my love affairs; my feelings are transformed.” Curiously, the central character in her flirtation spree confesses that she does not want to cut short the old relationship but spells out the contours of the relationship at the outset.

It looks surprising that the protagonist, who has a fierce penchant for male companionship, first underwent to homoerotic experience. In the life of desire, crush, infatuation, promiscuity, and fidelity are equally undifferentiated states of mind. It is an issue that remains unresolved which also appears a little too trite. Arafa Shazad’s lucent prose propped up by creative use of narrative devices does not produce a litany of daring sex acts. She deserves accolades for being commendably honest, and one can find its seemingly prurient content excruciating to read

Shafey Kidwai is a bilingual critic who got Sahitya Academy Award in 2019 for Urdu. He is professor of Mass Communication at Aligarh Muslim University.